Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) – Living Plant Wisdom Profile

Introduction: Yarrow as Teacher and Ally

In a world hungry for authentic connection to the earth, yarrow (Achillea millefolium) emerges as both ancient teacher and modern ally. This humble yet heroic plant—named for the Greek warrior Achilles who used it to heal battle wounds—carries within its feathery leaves and clustered white flowers the accumulated wisdom of millennia.

Yarrow is more than a medicinal herb or garden companion; it is a bridge between worlds. It connects the laboratory researcher documenting its anti-inflammatory compounds with the indigenous grandmother teaching children which plants heal. It links the regenerative farmer seeking to build soil health with the beekeeper watching clouds of beneficial insects visit its blooms. It joins the backyard gardener making fermented plant extracts with the viticulturist establishing pollinator corridors between vineyard rows.

What makes yarrow extraordinary is not just its versatility—though it serves as wound healer, fever reducer, soil builder, pest deterrent, and pollinator magnet—but its way of teaching us about reciprocity. This plant gives generously: its roots break compacted earth, its flowers feed countless beneficial insects, its leaves provide medicine for humans and animals alike. In return, it asks only for respectful harvest, grateful acknowledgment, and the chance to complete its life cycles.

This profile represents a new way of knowing plants—not as resources to extract from, but as teachers to learn alongside. Here, peer-reviewed research converses with traditional ecological knowledge. Scientific studies validate what indigenous peoples have known for generations, while ancient wisdom guides modern research toward questions worth asking. The result is neither purely academic nor purely traditional, but something richer: living plant wisdom.

As we face climate uncertainty, biodiversity loss, and disconnection from natural systems, yarrow offers a different path forward. It shows us how one plant can simultaneously heal bodies, build soil, support wildlife, and strengthen communities. It demonstrates that the medicine our world needs isn't found in separation—human from nature, science from tradition, farm from pharmacy, but in their thoughtful integration.

Whether you're a farmer seeking sustainable pest management, an herbalist exploring plant allies, a gardener wanting to support pollinators, or simply someone curious about deepening your relationship with the green world, yarrow has something to teach. Its story reminds us that the earth's medicine is both freely given and carefully tended, and that our role as earth stewards is to receive its gifts with gratitude while giving back with wisdom.

In the pages that follow, yarrow reveals itself as more than plant—as collaborator in the great work of healing our relationship with the living world.

Overview & Botanical Profile

Plant: Achillea millefolium – the common yarrow.

Common Names: Yarrow, common yarrow, milfoil, nosebleed plant, soldier’s woundwort, staunchweed, thousand-leaf, etc.

Family: Asteraceae (Compositae).

Native Range: Temperate Northern Hemisphere – indigenous to much of North America, Europe, and Asia. It grows from sea level to alpine zones (up to ~3500 m). The genus name comes from the Greek hero Achilles, who used it on wounds; the species name millefolium means “thousand-leaves” (a reference to its finely divided foliage).

Global Distribution: Now found nearly worldwide in temperate climates; naturalized in Australia/New Zealand and common along roadsides, pastures, meadows and disturbed sites. It is both cultivated ornamentally (white, pink, yellow or red cultivars) and freely self-seeds (sometimes becoming weedy).

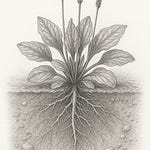

Physical Description: A hardy perennial forming erect clumps ~0.5–1 m tall. Leaves are aromatic, feathery, deeply bipinnate (fern-like) 5–20 cm long. Flower heads are flat-topped clusters (“corymbs”) of many tiny composite flowers. In wild types the blooms are usually white or pale pink, with both ray and disk florets. Yarrow often blooms from spring through fall (roughly April–October) in favorable climates. Plants spread by stout rhizomes and seed prolifically, forming open mats in sun-exposed sites. The whole plant has a strong, sweet-musty scent (some find it pleasantly herbal, others pungent).

1. Cultural Wisdom (Ethnobotany, Mythology, TEK)

Global Traditions: Across Eurasia and North America, yarrow has a deep ethnobotanical history. It was used by many Native tribes (Plains, Navajo, Miwok, Ojibwe, etc.) and by ancient cultures worldwide.

Historical and Indigenous usage: Traditional healers and herbalists valued yarrow as a multipurpose herb (a topiaca). It was applied fresh to bleeding wounds (as an antiseptic and styptic), and brewed as a tea for fevers, colds, coughs, and digestive complaints. European folk traditions called it “nosebleed plant” because crushed leaves staunched bleeding. Native Americans chewed it for toothaches and made earache infusions (the Navajo dubbed it “life medicine”). Other uses included cloth dye (flowers yield yellow-green), strewing in thatch or sleeping mats for fragrance and insect control, and brewing in ancient beer gruit. In Chinese tradition, yarrow (along with other herbs) was used in divination ceremonies and considered auspicious.

Integration into agricultural/seasonal cycles: Yarrow’s deep knowledge is reflected in its seasonal roles. Harvested at full bloom, it featured in women’s health tonics (promoting menstruation) and spring tonics (to “cleanse” and support liver/kidney). In farmsteads it was sown or allowed to self-seed among medicinal/herb gardens and orchard guilds. Traditional farmers knew yarrow signaled soil health: its presence indicated open, well-drained ground. In biodynamics, as prep #502, yarrow is made into a dew-harvested flower spray to enrich trace minerals in compost.

Mythology & Symbolism: Yarrow is steeped in myth. Greeks named it after Achilles’ legendary wounds; medieval Europeans saw it as a blood-stancher (“soldier’s woundwort” and “knight’s milfoil”). In folklore, yarrow was one of the “carpenter’s weeds” (legend has Joseph and Jesus using its springy stems), and in witchcraft it symbolized courage and protection. Some Native narratives regard yarrow as a feminine, nurturing herb of peace and healing. Symbolically it represents endurance, healing power, and “psychic protection” (ensuring one’s “psychic skin” stays intact in energetic practices).

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK): Indigenous stewards note yarrow’s roles in ecosystems. It commonly appears in meadows, roadsides, and fires’ aftermath. By spreading over disturbed soils, it quickly re-establishes cover and fertility: its deep roots break compacted ground and its decay returns nutrients. In community healing circles and sweatlodge ceremonies, yarrow might be burned as incense or used as a medicinal smoke to purify and draw in healing energies. Ethical gathering was taught – only harvest a portion of a patch, leaving “medicine for the land” and song offerings in thanks. Ceremonially, seeds and plants are often respectfully asked permission before taking, aligning harvest with moon phases and prayers.

Cultural Disruption & Rematriation: Colonial disruption scattered yarrow (originally native to North America in certain varieties) beyond its homelands, and indigenous knowledge of it was marginalized. Today, many communities work to reclaim yarrow’s heritage – planting native strains in repatriated medicine gardens, teaching youth about it, and protecting wild populations (which in some regions is considered a weed, but for First Peoples remains a sacred plant). Seed-saving projects aim for “rematriation”: ensuring local genotypes of Achillea are preserved. Contemporary herbalists and farmers honor yarrow by prioritizing sustainable harvest (never clear-cutting the herb, using hand-shear instead of mechanized mowing) and giving thanks in gratitude ceremonies.

2. Nutritional Profile & Health Benefits

Macronutrients: Yarrow is not consumed for calories (tiny herbaceous leaves) and offers negligible protein, fat, or carbs. Traditional use is culinary-therapeutic: young leaves may be sparingly added to salads or soups for flavor and mild nutrition.

Micronutrients: While data are limited, yarrow provides vitamins and minerals when consumed as tea or greens. It contains vitamin A and vitamin C, and minerals such as potassium, calcium, iron and magnesium. In herbal-spa contexts, yarrow baths are prized for trace elements; fields of yarrow yield biomass rich in silica and other micronutrients that concentrate in compost teas.

Bioactive Compounds: Yarrow is rich in phytochemicals. Its blue essential oil (from steaming flowering tops) contains proazulenes like chamazulene and δ-cadinol, which confer anti-inflammatory action. Its leaves and flowers supply salicylic acid (a natural aspirin precursor) and flavonoids (quercetin, apigenin, luteolin, etc.), plus phenolic acids (caffeic, ferulic, chlorogenic). The bitter sesquiterpene lactones (achilleine, etc.) give yarrow its taste and support digestive activity. Lab studies confirm yarrow extracts exhibit antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial effects attributable to these compounds.

Medicinal Uses & Clinical Evidence:

(a) Scientific Evidence: Clinical research on yarrow is still emerging but promising. Animal and in vitro studies show yarrow’s extracts can reduce intestinal spasms – a 2013 trial found hydroalcoholic yarrow extract significantly relaxed rat ileum contractions, supporting its traditional use for cramps, diarrhea and IBS. Another study in rats confirmed yarrow’s role as a hemostatic: a yarrow extract applied to liver incisions cut average bleeding time by ~32% compared to control. Some trials combine yarrow with other botanicals: e.g. an Iranian clinical trial found that a blend of yarrow, ginger and boswellia significantly reduced IBS symptoms and associated anxiety. Yarrow’s flavonoids and lactones are under study for antioxidant and mild analgesic effects; its essential oil shows mild wound-healing properties. However, rigorous human trials are few, so scientific consensus on dosage and efficacy is still limited.

(b) Traditional / Experiential Wisdom: Herbalists and indigenous healers have long administered yarrow for wounds and fevers. They make tea or infusion from flowering aerial parts to induce sweating (break fevers) and relieve colds, flu and menstrual cramps. A freshly crushed poultice or spit-wound dressing of yarrow is prized as a hemostatic and antiseptic. It is employed as astringent gargle for sore throats or as an eyewash for mild conjunctivitis in folk practice. Externally, yarrow tincture or infused oil is used on skin eruptions, eczema or bites due to its antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory reputation. Traditional Chinese and Ayurvedic systems recognized yarrow as blood-moving and cooling: it was used for menstrual regulation and to relieve intestinal gas. In farm herbalism, a few cups of yarrow tea is sometimes given to livestock (especially poultry) to improve appetite and purify blood.

(c) Safety & Contraindications: Generally yarrow is safe when used as an herb or tea, but caution is advised. Allergies: Like other Asteraceae, it can cause contact dermatitis or hay-fever in sensitive people. Reproductive: It may stimulate uterine contractions, so pregnant women are usually advised to avoid high doses (as it “induces menstruation”). Interactions: Its salicylates could potentiate blood-thinners; use cautiously with anticoagulant drugs. Pets/Livestock: According to the ASPCA, yarrow is toxic to horses, dogs and cats (causing vomiting, skin issues), and it can taint cows’ milk with bitterness. Use in edible products must follow local herbal safety guidelines (e.g. regulate dose, use labeled herbal tea grades). Drying and washing removes some compounds; always correctly identify Achillea (avoid look-alikes) and harvest from clean sites to prevent pesticide exposure.

3. Soil & Ecosystem Roles (Ecological, Agricultural, Regenerative)

Soil Building & Nutrient Management: Yarrow has a vigorous root system and contributes to soil health. Its deep rhizomes break up compacted earth and enhance aeration. As a perennial with lasting cover, yarrow reduces erosion – planting it on slopes or poor soils helps hold soil with its network of roots. The plant accumulates minerals from subsoil (e.g. calcium and potassium), which return to the surface when leaves fall or are composted. Indeed, biodynamic compost preparations call for yarrow flowers to create a soil stimulant: “BD #502 permits plants to attract trace elements in extremely dilute quantities for their best nutrition”. In practice, fermenting yarrow (as a Fermented Plant Juice or adding it to compost tea) yields a nutrient-rich microbial solution beneficial for seed-start and transplants. Gardeners report yarrow composts springing to life more quickly, suggesting it accelerates microbial decomposition.

Microbial life & nutrient cycling: Yarrow roots are colonized by mycorrhizal fungi and beneficial soil microbes. This symbiosis enhances nutrient uptake (especially phosphorus) for yarrow and neighboring plants. Its decaying biomass adds organic matter and food for soil bacteria, which in turn help cycle nitrogen. Some Korean Natural Farming practitioners use yarrow’s high mineral content – they ferment young yarrow shoots into FPJ (rich in nitrogen) and flowering tops into FPE (rich in potassium) – to boost soil fertility and plant vigor. Though not a legume, yarrow’s presence in cover-crop mixes can improve subsequent crop yields via these soil-building effects.

Biodiversity & Wildlife Support: Yarrow is an insectary plant. Its flat-topped clusters provide nectar and pollen to a wide array of beneficial insects. Bees, butterflies, hoverflies, tachinid flies and other pollinators love yarrow blooms. In vineyard trials, plots with yarrow had significantly higher counts of beneficial parasitic wasps and general predators than control groundcovers. Ladybugs, lacewings and syrphid flies commonly visit yarrow flowers to feed. As a host plant, yarrow supports caterpillars of several moth species and the larvae of soldier beetles. Birds also use yarrow: European starlings famously line nests with its herbs to inhibit parasites (experiments confirmed nests with yarrow had fewer parasites). Many butterflies (e.g. swallowtails) lay eggs on Achillea. Its season-long bloom (spring through fall) makes it a continuous resource.

Role as keystone/indicator species: Yarrow thrives in disturbed sites, meadows and open woodlands. Its early colonization of disturbed patches (e.g. firebreaks, field edges) illustrates its successional role: it prepares bare ground for other species by stabilizing soil and adding humus. In many regions it indicates healthy grassland or meadow ecosystems. Because it tolerates drought and poor soils, yarrow can be a leading indicator of lands in need of restoration (or conversely, indicator of well-draining, unflooded ground).

Succession & Ecosystem Stabilization: As a perennial with spreading roots, yarrow helps regulate water flow and reduce runoff. In riparian buffers or erosion-prone areas, a stand of yarrow mixes with grasses to slow water and capture sediments. Its deep roots improve water infiltration and may tap subsoil moisture, thereby stabilizing the microclimate. By staying green and present, it outcompetes weedy annuals on neglected land, aiding in meadow restoration. In temperate climates yarrow dies back in deep winter but leaves a protective mulch of leaves and stems that prevents soil erosion until spring.

Companion Planting & Pest Management: Yarrow is famous in polycultures and permaculture guilds. It reputedly attracts predators that hunt pests: aphid-eating hoverflies and ladybeetles often appear where yarrow grows. A classic guild is planting yarrow near fruit trees and vegetables – it is said to improve fruit set and deter nematodes. Indeed, a study in Quebec apple orchards found yarrow strips significantly reduced damage by the European apple sawfly: orchard rows next to yarrow had ~20–50% fewer sawfly eggs and larvae, indicating a repellent or confusing effect of yarrow’s scent. Experimental sprays of yarrow essential oil on blossoms confirmed the repellent effect on sawfly oviposition. Conversely, some pests are indifferent: e.g. companion yarrow did not reduce squash bug infestations in field squash trials, and may even harbor low levels of aphids (though generally their natural enemies follow). Empirically, many growers report that interplanting yarrow with brassicas or solanums can reduce flea beetle and caterpillar pressure, likely by increasing overall predator presence. Some also use yarrow decoction as a homemade spray – its essential oils have mild insect-repellent and fungistatic properties. In summary, yarrow rarely acts as a direct pesticide, but its strong aroma and ecosystem services often translate to net pest suppression when used in polycultures.

4. Bioenergetic Field (Quantum Biology & Vibrational Roles)

(Note: The following perspectives are speculative and draw on alternative, energetic paradigms.)

Energetic Signature (Flower essences, Biodynamic uses): In flower essence therapy, yarrow is seen as a “protective shield” flower. Practitioners of Bach or Soulflower essences note that Yarrow essence helps one maintain personal boundaries and cleanse negative energy without becoming rigid. It is said to allow openness and sensitivity while preserving inner integrity – akin to its role of protecting nestlings in the bird study. Biodynamic agriculture assigns yarrow to compost prep #502, believing it directs subtle forces that help plants uptake trace minerals. Anthroposophical farmers speak of yarrow drawing cosmic “silver light” into the plant (since its oil is blue), and carrying that subtle energy back into the soil via the compost preparations.

Quantum Biological Hypotheses: Some researchers in emerging phytobiology hypothesize that the complex mix of essential oils and pigments in yarrow might interact uniquely with light and magnetism. The blue chamazulene in yarrow oil is a powerful chromophore; one could imagine it playing a role in low-level light absorption or signaling in tissues (though this is not confirmed). Yarrow’s bio-photonic profile might produce weak electromagnetic fields that influence nearby plant cells or microbes. For instance, theories of plant communication suggest aromatic emissions could operate beyond simple chemical dispersal, perhaps affecting insect antennal detection thresholds or even plant-to-plant signaling. In biodynamics, stirring water with yarrow preparations is thought to create subtle vortex energies in the solution, energizing it for field application (this remains outside mainstream science).

Microbial & Energetic Signaling: Yarrow roots may emit exudates that shape rhizosphere microbiomes in special ways. Some hypotheses suggest that polyphenols from yarrow could act as signals, encouraging beneficial bacteria that produce plant hormones or bioactive compounds. On an “energetic” level, when yarrow is used in biodynamic spray, farmers claim the soil “feels more alive” – perhaps reflecting changes in microbial communication networks. Vibrational healers also mention yarrow’s role in balancing the electromagnetic field of the human aura or of living spaces; in feng shui, sprigs of yarrow are sometimes hung to ward off stagnant energy.

Hypothetical Field Effects: In subtle-energy traditions, yarrow is linked to the solar plexus and heart chakras, resonating with a golden-yellow energy (its flowers) that bolsters vitality and courage. Some gardeners describe walking by a yarrow patch and sensing a feeling of calm alertness – an “energetic tonic.” Ecophotonic studies might someday measure if fields around yarrow stands differ in photon emissions or electric potential compared to other plants. At present, these ideas remain conjectural, but they reflect an emergent view of plants as composed of both chemistry and information fields.

5. Animal Nutrition & Veterinary Applications

Animal Benefits & Uses: Yarrow is valued in folk veterinary medicine much as in human herbalism. It is often called a universal vulnerary for animals. For example, herbalists powder dried yarrow flowers as a “Wound Aid” – sprinkling it into bleeding cuts, goat scratches, or deep punctures on livestock and pets to staunch blood flow and disinfect. It is used as a poultice for ulcers or sores on dogs and horses. Internally, moderate doses of yarrow tea or tincture are given to animals to stimulate appetite and digestion or to clear fevers. In poultry, yarrow is reputed to help relieve respiratory infections. Home brewers of herbal bird tinctures sometimes include yarrow for its antiparasitic reputation. Sheep and goats may browse yarrow freely; it can act as a gentle dewormer.

Preparations/Methods:

Topical Poultice: Crush fresh yarrow, apply directly to wounds or oozing areas on animals (common in emergency field care). The saliva forms a quick clot. For farm use, a dried yarrow poultice or compress (soak herb in hot water, apply cloth) is standard. Veterinarians in herbal clinics may inject diluted yarrow extract around the wound edges to complement suturing.

Herbal Infusions: Prepare a mild yarrow tea (1–2%) and use as a wash for skin inflammation, ulcers or as an eyewash for conjunctivitis. Ingested in small amounts (cool tea or add to feed), it can promote diuresis and digestion in animals. Exotic pet keepers note yarrow helps cage birds with sinus infections (use as misting rinse).

Feed Supplement: Some holistic farmers mix dried yarrow into mineralized salt licks or herbal feed pellets to deliver trace minerals. However, care is needed: because yarrow’s bitter oils can taint milk and a strong smell can deter grazing, it is used sparingly as fodder (often cut and dried rather than fresh).

6. Practical Regenerative Applications (Hands-On Systems)

Garden Applications

FPJ/FPE Recipes: Yarrow is a star in Korean Natural Farming. Fermented Plant Juice (FPJ): Harvest young shoots or entire tops in vigorous growth (pre-flower stage), macerate and ferment under 2-bag fermentation to produce nitrogen-rich FPJ. Dilute 1:500 as a foliar feed during vegetative growth to boost leaf and stem health. Fermented Plant Extract (FPE): Collect blooming flower heads, ferment similarly to yield a potassium-rich FPE. Dilute 1:1000 as a bloom/fruiting tonic or soil drench after flowering. The resulting brews have a noticeably viscous, honey-like quality (due to polysaccharides) and a strong herb aroma.

Compost Activation & Mulch: Chop fresh yarrow stems and add to active compost piles to accelerate decomposition – the allicin-like compounds temporarily deter pathogens and nitrogen-fixers help break down woody matter. Fully decomposed yarrow compost is darker and richer. Alternatively, dry milled yarrow (leaves, stems and flowers) makes a fine mulch or soil amendment; applied thickly it suppresses weeds while gradually releasing nutrients. Yarrow’s fibrous tissue improves soil structure when used as rough mulch beneath fruit trees or berry beds.

Companion Planting & Seasonal Timing: In temperate gardens, sow yarrow seed indoors 8–10 weeks before frost, or direct-seed in spring after last frost (it germinates in 7–14 days). Space 30–45 cm apart in a sunny bed. Mature plants can be divided in spring or fall. Yarrow blooms first in early summer; cut a stemful for bouquets (encourages more blooms) and then use the rest as green manure or mulch in August. Its long-flowering habit makes it ideal at garden edges: it is often grown in pollinator hedgerows, butterfly gardens, and herbal border gardens alongside other perennials.

Companion Cropping: Pair yarrow with vegetables that benefit from pollinators or predatory insects. It is commonly interplanted with brassicas (cabbages, kale), nightshades (tomatoes, eggplants) and cucurbits. Gardeners note that yarrow’s scent seems to keep certain pests (like squash bugs and Japanese beetles) at bay. In flower beds, it blends well with ornamental herbs (mint, lavender), berries (currants, raspberries) and roses – improving bloom set and vigor.

Seasonal Notes: In spring, a flush of new growth can be harvested for teas or gentle tonics. Summer is peak flowering – use flowers fresh or dried for medicine, bouquet trade, or added to summer salads (leaves). Late-season (autumn) gather seeds by cutting flower heads when brown; dry them to scatter for next year or share with seed-savers. In fall, any cuttings can be composted or used as mulch. Yarrow generally stays erect through frost; a hard pruning after first light freeze can protect new basal shoots that emerge in late winter.

Orchard Applications

Guild Formation: Yarrow is a classic fruit-tree guild plant. Around apples, pears or stone fruits, plant yarrow near the dripline. Its white flower clusters act as “bug magnets” in spring, drawing pollinators and parasitic wasps to the trees’ blossoms. The strong scent also masks tree volatiles that pests use to locate fruit; anecdotal orchardists report fewer aphids and codling moths where yarrow blooms are abundant. Companion trees often see better fruit set and sweeter fruit (possibly from better pollination and nitrogen cycling).

Soil Improvement Strategies: Under fruit trees, use yarrow as a living mulch: broad, overlapping leaves suppress grass competition, while dense roots add organic matter and nutrients when they die back each year. In young orchard establishment, interplant yarrow with nitrogen-fixers (e.g. clovers) and dynamic accumulators (comfrey) to kickstart soil fertility.

Pest/Guild Management: The apple-sawfly trial suggests planting strips of yarrow along orchard edges or between rows can serve as a trap/repellent for early-season pests. Yarrow attracts predatory hoverflies and lacewings that feed on aphids and caterpillars. It can be interplanted with flowering buckwheat and mustard in spring cover crops to “green manure” and support beneficial insects. Yarrow foliage also deters vole activity in some orchards (they dislike walking on the aromatic foliage).

Water Dynamics: Because yarrow is drought-tolerant once established, it is well-suited for orchards on marginal soils or dry climates. It helps regulate excess irrigation by transpiring moisture through its many leaves, and its broad cover reduces surface evaporation. In flood-prone settings, its deep roots can help perk up soggy ground, while in arid zones it survives to provide cover when grass dies back.

Vineyard Applications

Flowering Groundcover: Many viticulturists now sow flowering cover-crop strips, and yarrow often leads the pack. In inter-row trials, yarrow stands produced 2–3× higher densities of beneficial wasps and bees than plain grass. Its flowers appear early in spring (even before some cover crops bloom), giving a nectar source when vineyards are otherwise bare. This sustains parasitoids (e.g. Anagrus wasps that attack leafhopper pests) during critical periods. Plant yarrow as permanent mid-row strips: it survives without irrigation and recovers each spring.

Disease Management and Vigor: Yarrow’s allelopathic resins may suppress certain fungal pathogens at the soil level, and its strong scent can confuse vineyard pest moths. It is also used in biodynamic spray #502 to “tonify” vine vigor, under the theory that the herb’s energetic imprint balances excessive vine growth (anecdotal and not field-proven, but practiced in some organic estates). In sandy or rocky vineyards (low-vigor sites), yarrow creates a living mulch that protects the roots of younger vines, builds topsoil, and supports microfauna that improve nutrient cycling.

Low-Vigor Zone Applications: Where vines are stunted (nutrient-poor soils), yarrow is planted to increase biodiversity and organic matter. Its capacity to accumulate potassium and silica may gradually improve soil fertility for the vines. In ultra-dry vineyards, yarrow stands capture every bit of dew and fog moisture – research on biodynamics suggests yarrow prep 502 sprays can magnetize the moonlight energies, aiding water retention (an untested hypothesis, but a traditional claim). Overall, vineyards with healthy yarrow edges report more consistent yields and healthier grapes, likely via the indirect support of ecosystem health.

7. Emerging & Underexplored Applications

Novel Medicinal/Nutraceutical: Scientists are isolating yarrow compounds for new therapies. Early studies suggest Achillea flavonoids may have anti-diabetic and anti-hyperlipidemic effects, and may enhance collagen metabolism (promising for metabolic syndrome and aging skin). Its antioxidant compounds are being tested in cosmeceuticals (yarrow extracts in anti-aging creams to lighten pigmentation). Yarrow also contains eupatilin and jaceosidin, flavonoids of interest in neuroprotective research (possible value in neurodegenerative disorders). In pharmacognosy, achilleine (an alkaloid) is under preliminary study for modulating pain pathways. The rich essential oil is explored in aroma-therapeutics and even livestock aromatherapy (diffusers in barns for pest control).

Innovative Agricultural Uses: As an industrial green solution, yarrow has potential. Its essential oil is being tested as a bio-insecticide; lab assays show it repels mosquito larvae and certain crop pests (drawing on [43] results). The concept of “allelopathic mulch” uses dried yarrow stalks as under-tree mulch to slowly release natural herbicides, suppressing weeds around high-value crops. Yarrow seeds are being evaluated for edible oil or beeswax alternatives. The plant’s fiber is fine and strawy – there is untapped potential in cordage or paper-making (researchers are investigating Achillea fiber as a sustainable resource). With climate stress, yarrow’s drought tolerance and frost resistance make it a candidate for carbon farming practices: perennial groundcovers like yarrow store more carbon year-round than annuals. There is interest in breeding high-proazulene cultivars as a natural colorant or fragrance source (chamazulene being the compound behind chamomile’s color).

Sustainable Industrial/Craft: Beyond medicine, yarrow has craft uses that can be scaled sustainably. Its flowers dye textiles a warm yellow to green; artisan dyers prize wild-harvested yarrow for natural silk and wool dyes (often mordanted with iron for olive greens). Yarrow honey (from bees foraging its blooms) is a specialty product commanding niche prices. In the beverage industry, commercial micro-brewers are reviving ancient “gruit” ales flavored with yarrow and other herbs (a gluten-free alternative brew). Florists use yarrow’s flat umbels in dried arrangements (the seeds and dried flowers keep shape), offering a sustainable cut-flower line. Even biodegradable seed mats impregnated with yarrow seeds are being trialed for rapid revegetation of disturbed soils.

Climate Resilience & Carbon Farming: Yarrow’s deep roots sequester carbon below ground; as a perennial cover, it builds soil organic matter quicker than annuals. It tolerates erratic moisture, so it is useful in climate adaptation plantings (windbreaks, buffer strips). There is emerging interest in using yarrow in regenerative ag. systems: for example, intercropping yarrow in fire-prone rangelands can reduce fire spread (its moist interior tissues resist ignition). Additionally, as a “bioaccumulator,” yarrow might be planted to phytoremediate heavy metals in soils (some studies show related Achillea species take up cadmium and zinc). Its resilience suggests roles in agri-ecosystem insurance planting.

8. Practical Applications & Revenue Streams (Farmstead Perspective)

Raw & Minimally Processed Products: Fresh yarrow bundles (culinary/herbal markets), dried flower/leaf (loose herb tea blends, sachets). Freeze-dried yarrow for herbal capsules. Fresh tincture or glycerite. Yarrow essential oil (though yield is low ~0.1%, niche market in aromatherapy and perfumery). Honey from apiaries placed in yarrow fields. Herbal lip balms or wound powders (the “Wound Aid” product). Seasonal fresh sprigs for floristry. Dried floral arrangements for home décor. Breweries or kombucha producers: small-batch yarrow mead or infused ciders.

Living Fertilizer Line: Bottled herbal nutrients: “Korean Natural Farming” style yarrow FPJ and FPE sold for organic gardeners. Custom compost activators blending yarrow with other dynamic accumulators (marketed by regenerative nurseries). “Probiotic” soil drenches using yarrow-ferment to promote beneficial microbes. Yarrow-based vermiwash (worm cast tea).

Animal-Related Products: Herbal equine or canine supplements containing yarrow (for arthritis or mild inflammation). High-magnesium mineral licks mixed with dried yarrow for cattle/sheep. No-harm pest woolies: satchels of dried yarrow for bee hives to deter wax moths. Yarrow tincture stalls for specialty veterinary apothecary.

Craft & Value-Added Goods: Edible: Yarrow-infused honey, flavored vinegars (culinary herb), teas blended with rosehips or mint. Alcoholic: Yarrow bitter liqueur, herbal bitters for cocktails. Natural dye kits (yarrow powder or dye bundles) for artisanal dyeing. Fiber: small-scale production of yarrow straw mats or insulation (experimentally, as a niche). Scent: aromatic bath salts and sachets. Dried seeds for bird feed mixes (millet alternative).

Agritourism & Education: Farm tours highlighting “medicinal meadow”, workshops on making yarrow salve or ferment, summer internships with hands-on permaculture healing-gardening. Medicine walks teaching indigenous uses (partnering with local tribes for authentic storytelling). Publishing local herb guides or children’s books featuring yarrow lore. Themed events (e.g. “Yarrowfest” in summer). On-site farm store selling all the above (teas, tinctures, wreaths).

Seed & Plant Commerce: Heritage seed packets of local Achillea ecotypes. Small-scale nursery stock sales for pollinator gardens and herbalists. Bulk seed for habitat restoration projects. White yarrow “green manure” seed coatings sold to farmers as cover crop. Possibly licensed genetic lines (e.g. patented low-lactone ornamental cultivars).

9. Practical Set-Up Timeline

Season

Activities & Recommendations

Spring:

Prepare site: choose a sunny well-drained area. Incorporate compost if needed. Sow yarrow seeds directly after frost (lightly rake soil); or plant nursery starts. Maintenance: Water until established; thin to 30 cm spacing. Mulch lightly. Inspect for early aphids – use beneficial insects. Harvest: New spring shoots can be harvested weekly for tea (boosts growth).

Summer:

Bloom Care: Pinch spent blossoms early in season to promote more flowers. Side-dress with compost or diluted FPJ in midsummer if leaves yellow. Harvesting: Cut flowers and leaves during full bloom (June-Aug): bundle for drying or infuse for medicine. Hang clusters upside-down in shade to dry. Leave some blooms for seed. Pest Management: Monitor mites (rare on yarrow) and treat with soapy spray if needed, since it attracts beneficial predators.

Autumn:

Seeding: Cut flower heads once brown; collect seed by shaking into containers or bagging heads. Save ~20% of seeds in situ for self-seeding next spring. Pruning: After first light frost, cut stalks about 10 cm above ground; chop them into compost or leave as mulch. Remove any diseased debris. Planning: Reserve divided clumps for propagation or transplanting; propagate by root division now or later.

Winter:

Seed Stratification: Cold-moist stratify saved seed if needed (yarrow benefits from chilly winter). Propagation: In mild climates, overwinter in-ground; in cold zones, ensure a 5–10 cm mulch layer for crown protection. Plan spring garden layout/guild design (include yarrow placements). Education: Host winter workshops on herbal preparations or fermenting stored yarrow biomass. Reflect on the past season’s yields and adjust planting density or harvest schedule.

10. Compliance & Safety Notes

Harvesting & Handling: Use gloves if prone to skin sensitivity. Harvest flowering tops midday on dry days (essential oils are most concentrated then). Avoid chlorinated water on plant-sprays (dilute FPJ with rainwater). If wild-harvesting, obtain permits where required and leave ample plants to reproduce.

Food Safety: Clean hands and utensils when processing herb. Dry in well-ventilated area to prevent mold; store in airtight containers away from light. Label clearly (Achillea can be confused with toxic fern-leafed plants). For teas, strain well (fine particles can cause throat irritation).

Regulatory: Yarrow is generally regarded as safe for traditional use, but check local herb regulations if selling products. In the U.S., yarrow used in foods or supplements must comply with FDA or state herbal guidelines (e.g. GRAS status). In the E.U., Achillea extracts are listed in some monographs, but products must be properly labeled with allergen warnings (due to pollen).

Contraindications: Acknowledge traditional warnings: not for pregnant/nursing without professional advice (can stimulate uterine tone). Label external products as “for external use only” on animals/pets, due to known pet toxicity. Maintain MSDS and ensure any staff know the plant’s allergenic potential (Asteraceae allergy). In compost teas (anaerobic extracts), maintain low microbial counts to avoid pathogen risk (fermented teas can support growth of Clostridium if mishandled). Always use clean equipment and note fermentation pH.

Ethical Considerations: Comply with biodynamic or organic standards if marketed as such (e.g. homeopathy or flower essences may have specific production standards). Respect indigenous intellectual property: if incorporating Native names or TEK, obtain proper cultural permissions and share benefits (e.g. revenue-sharing with tribal cooperatives when using traditional knowledge).

11. Experimental Testing & Farmer-Science

Design 1 – Beneficial Insects in the Garden: Setup: In a vegetable field, establish plots with and without yarrow flowering strips. Randomized block design, replicated 3–4 times. Treatments: “Yarrow plots” (15 m strips of yarrow planted mid-row) vs control (grass-only). Metrics: Weekly sticky-trap counts of predators (ladybugs, lacewings, wasps); aphid or caterpillar damage on adjacent crop (e.g. squash). Tools: Sticky traps, hand-counts under 10× microscope, plant damage ratings. Goal: Quantify any increase in beneficials and corresponding pest reduction due to yarrow cover.

Design 2 – Soil Fertility & Crop Yield: Setup: Test yarrow as a green mulch in fruit guilds. Design small orchard blocks where one group has yarrow interplanted (annually mowed as mulch) and another has conventional mulch (grass/lawn clippings). Metrics: Soil organic matter (SOM), nutrient levels (NPK, trace minerals by lab tests) measured annually. Tree growth and fruit yield recorded over 3–5 years. Microbial soil assays (qPCR for mycorrhizal fungi) to detect differences. Tools: Soil test kits, scales for yield, GPS mapping for plant cover, metagenomic sequencing for microbes. Goal: Determine if yarrow in the mix improves soil quality and crop output.

Design 3 – Medicinal Efficacy of Preparations: Setup: Preparation of yarrow extracts (water, ethanol, oil, ferment) to test on model organisms. Example: test hemostatic effect of fresh yarrow vs dried powder on a standard bleeding model (in vitro clotting time assay or animal model). Another: antispasmodic activity on isolated gut tissue (compare yarrow vs control as done in [38†L317-L325]). Metrics: Clotting time, magnitude of muscle contraction (tension transducer), inflammation markers. Tools: Lab bioassays (e.g. organ bath, spectrophotometer for clotting), replicates for statistical analysis. Goal: Validate or quantify the most common traditional uses (e.g. hemostatic, antispasmodic).

Design 4 – Pollinator Attraction Trial: Setup: Use potted plants or a small field of flowering yarrow to observe insect visitation. Over a two-week bloom period, collect and identify insect visitors by sweep net or camera trap. Compare with a control plot of a neutral plant (e.g. lettuce). Metrics: Pollinator diversity (species count), visitation frequency per plant. Tools: Insect identification guides, digital logbook. Goal: Document the specific pollinator species attracted to yarrow and quantify its value as insectary plant.

Farmer-Science Collaboration: Encourage farmers to use simple metrics: “count the pest vs predator insects on a test plant vs a control plant weekly,” or “weigh crop yields with vs without yarrow cover.” Citizen-science apps (PlantNet for ID, local weather station data) can augment measurements (e.g. correlation of yarrow bloom date to first bee arrival). Shared notebooks and photo journals of results foster communal learning.

12. Wisdom Carried Forward (Reciprocity, Ethics, Stewardship)

Yarrow teaches us to honour reciprocity and stewardship. Ethical harvesting means never “take all” – leave plenty of flowers and seeds for wildlife and future growth. Traditional ethic dictates asking the plant’s permission (in prayer or intention) before harvesting, and offering thanks in return. Returning pruned yarrow clippings and spent flowers to the earth (as mulch or compost) exemplifies reciprocity, feeding the soil with the plant’s own energy. Many indigenous cultures emphasize that “medicine comes at a price” – the harvest is done gently, intermittently, and with gratitude.

Contemporary seed sovereignty efforts encourage keeping local yarrow strains unhybridized, sharing seeds through community seed libraries, and using open-pollinated rather than proprietary varieties. By planting yarrow in gardens we also give back to pollinators – a gesture of care for the web of life that cares for us. When using yarrow knowledge (especially indigenous uses), we give credit to source communities: citing native names, inviting tribal elders as teachers in workshops, and protecting traditional knowledge with care.

Personal stewardship can include reflecting on one’s connection with yarrow: e.g. meditating in a circle of yarrow plants and noting insights, or journaling after making a healing salve. Intuitive farmers often say yarrow teaches them boundaries – to be open yet protected, mirroring the plant’s tendency to shield its nest and neighbors. Let that “lesson” guide our relationships: be sensitive to other beings, but maintain integrity and generosity.

13. Reflection & Wisdom Insights

Yarrow’s story bridges millennia: it is a humble herb with heroic tales (Achilles’ wound), a wildfield guest turned garden hero. The balanced profile above shows how living wisdom emerges by weaving (a) scientific facts, (b) millennia of experience, and (c) intuitive visions.

Integration of Knowledge: We saw that much of yarrow’s reputed power (hemostasis, antispasmodic, soil-building) is confirmed by studies. Yet science still chases what our ancestors knew by observation: that this plant heals cuts, cures fever, and draws life back into tired earth.

Holistic Use: In practice, the line between garden and medicine, farm and ritual, becomes blurred with yarrow. A farmer uses it to improve soil health and also to heal a neighbor’s wound – because earth medicines are of the earth in body and soul. This herb embodies regenerative ethics: it participates in all levels of ecosystem function, and expects care in return.

Cultural Respect & Sharing: Learning yarrow’s story demands respect for the cultures that cultivated its lore. As modern stewards, we are carriers of both plant genetic resources and cultural heritage. That dual responsibility calls for humility (honouring safety rules, not over harvesting) and generosity (teaching others, giving seeds away).

Emerging Curiosity: The frontier of plant wisdom keeps expanding. Questions like “how do plant vibes work?” or “can yarrow’s energy be measured?” push us to hold science and mystery together. Yarrow invites experimentalists, herbalists and dreamers to converse – it’s a teacher of both empirical inquiry and felt knowing.

In summary: Yarrow is a model of sustainable integration – a healer for people, a benefactor for gardens, and a spirit friend for the land. Its living profile reminds us: to steward nature is to drink from an ancient well of wisdom, yet always look deeper with fresh eyes.

Bibliography & References

Buckley, K. L., Seymour, L., Lauby, G., & James, D. G. (2014). Native habitat restoration in vineyards as an IPM strategy. Washington State University. (Conference proceedings: beneficial insect attraction by native groundcovers, including Achillea).

Farasati Far, B., Behzad, G., Khalili, H., et al. (2023). “Achillea millefolium: Mechanism of action, pharmacokinetic, clinical drug-drug interactions and tolerability.” Heliyon, 9(12), e22841. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22841.

Kazemian, A., Toghiani, A., Shafiei, K., et al. (2017). “Efficacy of a Boswellia, Zingiber, and Achillea mixture for irritable bowel syndrome.” Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 22, 120. doi:10.4103/jrms.JRMS_905_16.

Kahn, B. A., Rebek, E. J., Brandenberger, L. P., et al. (2017). “Companion planting with white yarrow or feverfew for squash bug management.” Pest Management Science, 73(3), 582–588. doi:10.1002/ps.4469.

Moradi, M.-T., Rafieian-Koupaei, M., Imani-Rastabi, R., et al. (2013). “Antispasmodic effects of yarrow (Achillea millefolium) extract in isolated rat ileum.” African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines, 10(6), 499–503.

Prindle, T. (ed.). (1994–2023). Yarrow (Achillea millefolium). NativeTech – Indigenous Plants & Native Uses in the Northeast. Retrieved 2025, from https://nativenortheast.com/yarrow/:contentReference[oaicite:95]{index=95}.

Rey-Vizgirdas, E. (2020?). “Common Yarrow (Achillea millefolium)”. U.S. Forest Service – Celebrating Wildflowers. Retrieved 2024, from https://www.fs.usda.gov/wildflowers/plant-of-the-week/achillea_millefolium.shtml:contentReference[oaicite:96]{index=96}:contentReference[oaicite:97]{index=97}.

Verma, P., Verma, V., & Thakur, R. (2017). “Chemical composition and allelopathic, antibacterial and antifungal activities of Achillea millefolium L. grown in India.” Industrial Crops and Products, 104, 144–150. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.04.046.

Yaghoobi, F., Khalati, F., et al. (2022). “Safety and hemostatic effect of Achillea millefolium L. in localized bleeding.” Hepatology Forum, 5(1), 25–27.

Additional resources: Duke, J. A. (2002). Achillea millefolium. In: Native American Ethnobotany Database. Univ. of Michigan.; Moerman, D. E. (1998). Native American Ethnobotany. Timber Press. (Doc cited via NativeTech and related ethnobotanical compilations); American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (2023). Toxic and Non-Toxic Plants List. ASPCA; C. Kothari (2024). “Yarrow/ Achillea millefolium: Health benefits…” Netmeds Health Library.

Share this post