This is it—the most expansive, layered, and revealing deep dive I've ever done in the Weeds of Wisdom series.

We often walk past dandelions without a second thought. But what if I told you that this common "weed" holds profound teachings for our bodies, our soils, and even our spirits? What if the plant we try so hard to pull out is actually here to heal?

This 70-minute podcast is not just about dandelion—it's about unlearning everything you thought you knew about weeds. It's a full-spectrum journey through its ecological, medicinal, cultural, and vibrational wisdom. After this episode, you’ll never look at a dandelion the same way again.

Let’s reintroduce ourselves to the plant that’s been trying to talk to us all along.

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) – Living Plant Wisdom Profile

Introduction: Dandelion – The Weed That Whispers Wisdom

What if the most misunderstood weed in your garden was actually one of the most powerful allies for soil, body, and spirit? Welcome to one of the most comprehensive explorations ever written on the humble dandelion – a plant so common it’s often overlooked, yet so profound it has quietly nourished ecosystems, healed generations, and inspired mythology across the world.

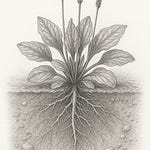

In this Plant Wisdom Profile, we trace dandelion’s journey through botany, medicine, cultural reverence, regenerative soil science, and even vibrational healing. This isn’t just a weed—it’s a master teacher in disguise. From its deep taproot that fractures soil and brings up nutrients, to its ancient use as a “blood cleanser” and its modern reawakening as a metabolic and microbiome ally, the dandelion reveals layer after layer of interwoven wisdom.

Whether you're a homesteader, herbalist, farmer, or someone seeking reconnection with nature’s quiet intelligence, this piece will change how you see that bright yellow bloom forever. It’s time to lean in and listen—because this “weed” has something to say.

Overview & Botanical Profile

Plant: Taraxacum officinale (common dandelion) – a herbaceous perennial in the daisy family (Asteraceae). The Latin epithet officinale means “of the apothecaries,” reflecting its historical medicinal use.

Common Names: Dandelion (from French dent de lion, “lion’s tooth,” describing the jagged leaves). Other names include blowball, puffball (for its seed heads), and in French pissenlit (“wet-the-bed”) referring to its famed diuretic effect. Indigenous languages and cultures have their own names; for example, in Chinese it is pugongying (蒲公英), and some Algonquin communities knew it as a spring blood tonic (greens eaten for health).

Family: Asteraceae (Sunflower or Daisy family), sharing traits like composite flower heads and milky sap with its relatives.

Native Range: Temperate Eurasia (Europe and Asia). Dandelion is believed to have originated in Europe, spreading through Eurasia long before human agriculture. Early European colonists intentionally brought dandelion to North America as a food and medicinal crop.

Current Global Distribution: Now naturalized worldwide, found on every continent except Antarctica. It thrives in temperate regions across North America (all 50 U.S. states and all Canadian provinces), South America, Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and much of Asia. Dandelion readily establishes in lawns, gardens, pastures, roadsides, and disturbed soils, wherever moisture and sun are available.

Physical Description: Dandelion forms a low rosette of deeply lobed, tooth-edged leaves up to 5–45 cm long. It has a stout taproot that can plunge up to 2 meters (6+ feet) deep into soil, sometimes branching and bringing up subsoil nutrients. When cut, the plant exudes a milky white latex sap. In spring and summer it sends up hollow, leafless flower stalks (5–30 cm tall) bearing single bright yellow flower heads composed of many tiny strap-shaped florets. These sunny blooms mature into globe-like seed “clocks” – white puffballs of tufted seeds that disperse freely on the wind. A single plant can produce several thousand seeds annually, and each seedhead carries up to ~180 seeds on average. Seeds germinate easily given light and moisture, and fragments of root can also regenerate new plants. Extremely hardy, dandelion tolerates crowding, foot traffic, mowing, and temperature extremes, even remaining green under snow in milder winters. This humble yet resilient form helps dandelion persist almost indefinitely – individual plants can live 10–13 years in undisturbed sites.

1. Cultural Wisdom (Ethnobotany, Mythology, TEK)

Global Traditions:

Scientific Evidence: Ethnobotanical surveys confirm that Taraxacum officinale has been embraced in folk medicine and cuisine on nearly every continent. For example, it has been used for at least a thousand years in Traditional Chinese Medicine as a heat-clearing, detoxifying herb (known as “Pu gong ying”) for ailments like infections and breast inflammation. In Europe, written records from the 16th century praise dandelion for treating maladies of the liver and spleen. The plant’s introduction to North America is documented in colonial texts; settlers and Indigenous peoples alike began using it as both food and medicine by the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Native American ethnobotanical databases note its adoption as a spring tonic and blood purifier once it naturalized in Indigenous territories. These cross-cultural records demonstrate how Taraxacum seamlessly integrated into healing traditions worldwide.

Traditional / Experiential Wisdom: Across the globe, dandelion earned a place in the kitchen and apothecary through direct experience. In Europe, rural peoples viewed young dandelion greens as a nutritious spring green (“pissenlit” in French folk usage, taken to “clean the blood” after winter) – often eaten fresh in salads or pot-herbed as a cleansing tonic. Europeans also roasted its roots as a coffee substitute when coffee was scarce, and fermented the golden flowers into the classic dandelion wine, a homemade country wine steeped in tradition. In China and Korea, dandelion is both a wild vegetable and a remedy; the leaves are stir-fried or steeped as a tea for their cooling, detoxifying effects, and the whole plant is used to support lactation and resolve abscesses or boils. In Indigenous North American communities, dandelion was incorporated post-contact as a welcomed new medicine: for instance, the Ojibwe and other nations made infusions of the root or leaf for heartburn and as a general tonic, and some First Nations ate the boiled greens to strengthen the blood. In Ayurvedic and Unani (Middle Eastern) medicine, dandelion is appreciated for liver complaints and as a mild laxative, paralleling its European “disorder-remedy” reputation. Around the world, dandelion became a “commoner’s cure” – freely available, trusted for gentle but noticeable effects on digestion, skin conditions, and overall vitality. Farmers and herbalists passed down recipes like dandelion leaf tea for jaundice or simmered dandelion in soup for wellness. This wealth of hands-on wisdom shows a remarkable convergence: whether in a Bavarian village or on the Great Plains, people learned that the “weed” underfoot was in fact a gift – a nourishing food and dependable healer handed to them by the land.

Emerging Hypotheses / Vibrational Theories: Beyond physical uses, many traditions assign energetic qualities to dandelion. Some Native American stories portray dandelion as a resilient spirit – one tale tells of a golden-haired maiden (the dandelion flower) who ages into a white-haired form whose children (seeds) fly with the sighing breath of the South Wind. Such folklore hints at dandelion’s role as a bearer of wishes and continuity, bridging generations. In contemporary flower essence therapy (a vibrational healing modality), dandelion is used to release emotional tension and stored anger in the body – practitioners report that its essence helps dispel inner “tightness” and restore sunny, effortless energy flow. This resonates with traditional views of dandelion as an uplifting presence: for example, its signature bright yellow is associated with the sun and often believed to bring cheer and courage to the spirit. Healers across cultures might say that the plant’s “energy” is one of resilience, joy, and gentle cleansing. These emerging vibrational interpretations, while anecdotal, echo the reverence found in myth – suggesting that the dandelion’s gift is not only chemical but also spiritual, imparting qualities of adaptability, optimism, and the power to thrive through adversity.

Mythology & Symbolism:

Scientific Evidence: The symbolic importance of dandelion is reflected in historical literature and ethnographies, though not measured in labs. Nonetheless, the pervasiveness of dandelion in human stories can be noted: a 2014 educational study highlighted that because Taraxacum exists in so many folkloric traditions, it serves as a relatable tool for teaching science to children across cultures. This indicates how deeply the plant is embedded in cultural consciousness worldwide. Many languages incorporate dandelion’s traits into its name – for instance, the English “dandelion” itself comes from medieval French dent-de-lion (“lion’s tooth”), a nod to leaf shape that became a metaphor for fierce survival. Even without formal “mythology data,” the plant’s recurring presence in art, lullabies, and superstitions is well documented by cultural historians, validating that dandelion is more than botanical fact – it is a cultural symbol.

Traditional / Experiential Wisdom: Dandelions have inspired rich symbolism, folklore, and sacred associations in many cultures. In European folklore, the dandelion is famous as the “wishing flower.” Children (and the young at heart) traditionally blow on the seedhead to make wishes – it’s said that if you can blow off all the tufted seeds in one breath, your wish will come true (and the number of seeds left might even tell how many years until marriage or how many children you’ll have!). Dandelion seeds are also used to tell time in some English traditions – the term “dandelion clock” refers to the idea of blowing the clock to predict the hour by how many puffs it takes to disperse the seeds. In Celtic lore, dandelions were associated with the sun’s power – their golden blossoms represented the sun’s strength, and their habit of closing at night and opening with the morning sun linked them to diurnal cycles and solar worship. People saw them as symbols of faithfulness and happiness, always greeting the day. In Chinese symbolism, the dandelion can represent perseverance (the plant that grows anywhere) and is sometimes included in art as a motif for wishes or as a reminder of life’s transience (the brief bloom and the flying seeds illustrate the impermanence and spread of one’s legacy). Myths and sacred practices also rose around dandelion’s practical uses: In some early monastic gardens in Europe, dandelion was grown as a cherished herb, and it earned nicknames like “Priest’s Crown” (for the bald seed head looking like a tonsured monk) and “Swine’s Snout” (from an old tale observing pigs seeking them out). Culturally, dandelions often symbolize resilience, hope, and the return of life in spring – they are among the first flowers to dot the spring landscape, a bright herald to communities that winter is ending. In countless societies, making tea or salad of the first dandelion greens is a ritual of renewal. Folklore across Europe warned against picking dandelions or you’d wet the bed (a nod to its diuretic power) – a superstition that actually helped protect this useful plant from overharvesting by children. From being the subject of poetry (as in poems that liken the puffball to stars or angels) to featuring in heraldry and festival traditions, the dandelion’s mythic and symbolic tapestry is as abundant as its seeds. Each puff of seeds carries not just future flowers, but human wishes, wisdom, and whimsy, connecting people to childlike wonder and the cycles of nature.

Emerging Hypotheses / Vibrational Theories: Modern nature spirituality and herbal circles often interpret dandelion’s symbolism in energy terms. For example, some view dandelion’s deep taproot as symbolizing groundedness and digging into one’s own soul – an energetic lesson in staying rooted while also spreading one’s gifts freely (as the seeds on the wind). Intuitives claim the plant’s sunny demeanor can energetically brighten the aura, and its airborne seeds teach the wisdom of letting go and trust – that one’s ideas or “seeds” will find fertile ground elsewhere. These are not scientific doctrines but personal insights that align with the mythic narrative: they propose that the spirit of dandelion helps people release burdens (mirroring its physical detox effects) and encourages a cheerful, unyielding outlook. In some New Age and neo-shamanic practices, dandelion is even included in rituals or flower essence blends to invoke its reputed ability to clear emotional stagnation and connect a person with the joy of sunlight. While such interpretations remain speculative, they carry forward age-old symbolic wisdom in a contemporary context, reinforcing the notion that this humble plant is a teacher of resilience and joy on multiple levels.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK):

Scientific Evidence: Field research and ecological surveys provide evidence that traditional land stewards (such as Indigenous farmers or pastoralists) often incorporated spontaneous plants like dandelion into their understanding of ecosystem health. For instance, scientists have observed that dandelion can serve as an indicator plant for certain soil conditions – it favors soils relatively rich in potassium and somewhat deficient in calcium. This aligns with what many traditional farmers noted: an abundance of dandelion in a pasture might signal a need for lime (to raise calcium and pH) or an indication of fertile, potassium-rich soil. Traditional Ecological Knowledge is reflected in these observations. In Alaska, ethnobotanical records show the Gwich’in people recognized that areas with thriving dandelions were good for certain grazing animals, indicating palatable forage. Such TEK observations have been corroborated by modern range science – for example, range studies confirm that dandelion is readily eaten by deer, elk, and other wildlife in spring and is especially prevalent in overgrazed or disturbed sites. Thus, TEK holders effectively identified dandelion’s role as both signal and participant in the ecosystem, knowledge now supported by scientific range ecology.

Traditional / Experiential Wisdom: Traditional Ecological Knowledge sees plants like dandelion as part of a reciprocal system of care between humans and the land. In many Indigenous and local farming traditions, dandelion is not considered a “weed” but a helper: it aerates and loosens hard ground with its taproot, its decaying leaves enrich topsoil, and it provides food for pollinators early in the season. For example, some Native American gardeners allowed dandelions to grow around the edges of their cornfields, understanding that the dandelions would attract bees and other insects that also pollinate crops (and in turn, dandelion’s presence did not significantly harm the corn). In traditional permaculture-like approaches worldwide (even if not called that), farmers observed that dandelions tend to appear in disturbed or depleted soils – rather than immediately uprooting them, wise land stewards interpreted this as nature’s way of healing the soil. Experientially, they noticed that dandelion’s deep roots break up compacted earth and bring nutrients to the surface, so they might let them grow for a season or two before turning them under as green manure. Integration into seasonal cycles was also key: many cultures have seasonal practices involving dandelion harvest that coincide with ecological needs. In spring, harvesting young dandelion greens for food doubles as a thinning that prevents complete takeover of a pasture, striking a balance between use and conservation. Traditional orchardists in Europe would allow dandelions to flourish beneath fruit trees until just before they seed – benefiting from their bloom and then mowing to keep them in check. This practice, guided by experience, prevented competition while utilizing dandelion’s ecosystem services (like attracting beneficial insects and possibly aiding fruit ripening through ethylene gas, a phenomenon European farmers noted intuitively long ago). In essence, TEK teaches stewardship practices that incorporate dandelion rather than eradication: rotational grazing that lets animals eat dandelions (turning a “weed” into forage), the making of “weed teas” and compost from dandelion (returning its minerals to the soil), and the conscious leaving of some dandelion patches as habitat for insects. There are also ethical relationships and ceremonies connected to plants like dandelion. For instance, some herbalists of First Nations background include a small offering (tobacco or prayer) when picking dandelion, even though it’s abundant – acknowledging the plant’s spirit and asking permission. In rural Europe, one might find a tradition of thanking the first dandelion of spring with a wish or a coin left at its base, a gesture of gratitude for the year’s bounty to come. Such practices illustrate TEK’s core principle: a respectful dialogue with the plant. Dandelion, in TEK perspective, is a community member – an ally that appears where needed and responds to how we treat the land, thriving in reciprocity when understood and utilized wisely.

Emerging Hypotheses / Vibrational Theories: In modern regenerative agriculture circles (which often integrate TEK with agroecology), some practitioners speak of a “subtle communication” with weedy pioneer plants like dandelion. This concept, while not fully scientific, echoes TEK’s intuitive grasp of plant roles. It posits that weeds carry messages about the land’s state and can even respond to farmers’ intentions. For example, an emerging hypothesis is that dandelions show up to repair compacted, mineral-deficient soils – their presence is a signal to the farmer to address soil health, either by letting the dandelions do their work or by amending the soil (the idea being that once the soil improves, dandelions naturally recede as they’re no longer “needed”). Some regenerative farmers almost playfully refer to dandelions as “soil doctors” sent by Mother Earth – a vibrational or spiritual way to frame what soil science confirms about nutrient accumulation and soil structure improvement. Additionally, biodynamic farming (an approach that interweaves energetic concepts with TEK) explicitly values dandelion: the Biodynamic Preparation 506 uses buried dandelion flowers to tune the soil’s energetic balance (it is said to help the soil “attract cosmic influences” and manage silica and potassium relationships). This preparation stems from Rudolf Steiner’s hypothesis that plants like dandelion have cosmic roles in the field’s energy matrix. While conventional science doesn’t measure “cosmic forces,” biodynamic farmers report practical benefits such as more harmonious orchard growth when dandelion prep is used – which could correlate with subtle changes in nutrient availability or microbial activity. In summary, emerging paradigms suggest that by reading and working with the energy and signals of dandelion, land stewards can enhance ecosystem health. This vibrational view beautifully dovetails with traditional knowledge: both see dandelion not as an invader to battle, but as a wise and communicative presence – an early volunteer in disturbed ground whose very existence is a guide toward healing the land.

Cultural Disruption & Rematriation:

Scientific Evidence: The history of dandelion’s spread and its shifting perception can be traced through botanical and sociological records. Colonization and modernization dramatically changed human-plant relationships: for instance, colonial records show that European settlers brought dandelion to North America intentionally, but by the 20th century it was being labeled a noxious weed in agriculture and lawns. The impact of this “cultural disruption” is evident in the data: millions of dollars have been spent on herbicides to eradicate dandelions in lawns and crop fields, and yet ecologists note that dandelion persists and even flourishes in modern chemically-managed landscapes, sometimes evolving resistance to herbicides. This suggests a resilient biological response to cultural attempts at suppression. Ethnobotanical scholars also document how the loss of traditional foraging practices (due to urbanization and colonial attitudes that belittled Indigenous knowledge) led to a decline in using dandelion as food/medicine in some populations during the mid-20th century. Only recently, scientific research into wild edibles and herbal medicines has resurged, validating many traditional uses of dandelion and thereby contributing to a rematriation of knowledge – returning respect and legitimacy to what was once dismissed as “old wives’ tales.” For example, clinical studies now investigating dandelion’s diuretic and anti-diabetic effects lend scientific credence to folk uses, helping restore this plant’s reputation as valuable rather than valueless.

Traditional / Experiential Wisdom: Colonialism and modernization disrupted the continuous thread of plant wisdom in many cultures. What happened with dandelion is illustrative: European colonizers spread the plant globally (often unintentionally furthering its range beyond their settlements), yet at the same time, colonial mindset tended to devalue the very plants they brought once “controlled” agriculture took root. Dandelion went from a beloved cottage remedy and common meal in Europe to being scorned as a “pesky weed” in prim lawns and industrial farms. In North America, Indigenous communities who adopted dandelion found that later, government and missionary schools discouraged traditional foraging – children were taught to regard such practices as backward. Thus, a rich body of knowledge about using and coexisting with dandelion was fragmented or lost for a time. Modern landscaping ideals also played a role: the rise of the perfect suburban lawn (often traced to post-WWII culture) demonized dandelions. Many children of the 20th century grew up hearing only that dandelions must be poisoned or plucked out, a far cry from their grandparents who might have picked them for supper or medicine. This shift represents a cultural disconnection from the plant. However, in recent decades a rematriation movement has begun – a return of the plant to cultural prominence and a restoration of respect for ancestral knowledge. Herbalists, foragers, and Indigenous elders are reviving the old recipes and teachings: community workshops now teach urban folk how to harvest dandelion greens safely, how to make dandelion root tincture, and how to appreciate the plant’s role in the ecosystem. Rematriation (a term implying restoring the nurturing, maternal relationship with the Earth and its seeds) can be seen in projects where Indigenous groups reintroduce traditional plants to their food systems. While dandelion is not native to the Americas, some Indigenous chefs and healers include it in decolonized diets as one of the wild greens that sustained people when commodity foods failed – reframing it from “colonizer’s weed” to “ally in survival.” Ethically, land stewards are now pushing back against the chemical warfare on dandelions: campaigns like “No Mow May” in North America encourage homeowners to let dandelions bloom for the bees in spring, thus challenging the culturally imposed aesthetic that a good lawn is a dandelion-free lawn. In some ways, the dandelion has become emblematic of a broader cultural healing: communities planting pollinator gardens now often include dandelions on purpose, and city policies in places like Canada and Europe have moved to ban harmful lawn pesticides, indirectly protecting dandelions. Efforts for restoration or protection of dandelion also occur in more informal ways – for example, seed savers and gardeners have actually developed and shared non-bitter cultivars of dandelion (sometimes called “Italian dandelion,” though that’s often a chicory relative) to encourage people to grow and eat them as they would lettuce. This is a cultural pivot back towards valuing the plant. Heirloom seed exchanges might include dandelion seeds from old homestead lines, ensuring the plant’s genetics and heritage usage are preserved. In essence, after a period of vilification, the narrative is coming full circle: farmers and herbalists are rematriating dandelion by re-integrating it into farms, gardens, and kitchens in a respectful, sustainable way, much as their ancestors once did.

Emerging Hypotheses / Vibrational Theories: The concept of plant rematriation also has a spiritual dimension. Some theorists suggest that as humanity faces ecological and health crises, certain plants (dandelion among them) are “calling us back” to wiser ways. A vibrational hypothesis might say that dandelion’s widespread resurgence – cracking concrete in cities, popping up in organic farms – is not accidental but a response by the Earth to our needs. In this view, dandelion carries an energy of resilience and healing specifically suited for our times, and it’s proliferating now to help remediate both soils and souls. Whether or not one subscribes to that level of agency, it is true that dandelion thrives in disturbed environments, which the modern world has in abundance. The speculative idea here is that dandelion’s spirit is aiding in regenerating landscapes we’ve disrupted (physically and culturally), hence “she” – dandelion as a feminine, life-giving force – is rematriating herself into our lives. This perspective encourages a reciprocal relationship: just as dandelion appears to help heal post-industrial wastelands and nutrient-depleted yards, we are invited to honor and welcome her rather than reject her. Some energy healers even meditate with dandelion, imagining a two-way healing: the plant helping to pull out the “toxins” of modern living (stress, fragmentation) from people, while people consciously protect and propagate the plant. These vibrational theories are poetic and not empirically proven, yet they resonate with many seeking to mend the human-nature divide. It reframes the narrative of dandelion from one of invasive weed to one of returning grandmother – bringing ancient wisdom back to her estranged family. The ongoing cultural shift toward organic land care, herbal medicine revival, and Indigenous knowledge reclamation all support this metaphorical interpretation. In practical terms, it means more people saving dandelion seeds, sharing folk recipes, and teaching the next generation to blow those puffballs and make a wish – a simple childhood act that ensures the continuity of both the species and its wisdom. The reverence and reciprocity embodied in rematriation efforts signal a healing of the disruption: each dandelion allowed to grow in one’s yard or farm is a small victory for cultural and ecological restoration, an acknowledgement that we need our weeds, and our weeds need us, to create a balanced, healthy future.

2. Nutritional Profile & Health Benefits

Macronutrients:

Scientific Evidence: Dandelion greens (the leaves) are highly nutritious for a wild vegetable. According to USDA data, a 100 g serving of raw dandelion greens provides about 45 kilocalories, mostly from carbohydrates (~9.2 g) and fiber (~3.5 g). They contain roughly 2.7 g of protein per 100 g – quite notable for a leafy plant – and only about 0.7 g of fat. The roots, being rich in inulin (a fructooligosaccharide), have a higher carbohydrate content, especially in the fall when they store energy as inulin (which acts as a prebiotic fiber). Scientific analysis shows dandelion’s protein contains a good range of amino acids, and though it’s not a high-protein food by weight, it exceeds the minimum protein requirements for deer and cattle maintenance when grazed fresh. This explains why livestock readily eat it. The fiber in dandelion greens (mostly insoluble fiber) supports healthy digestion and has a mild laxative effect. In terms of energy, dandelion is low-calorie but very filling due to fiber. These macronutrient profiles have been confirmed by multiple analyses and reviews.

Traditional / Experiential Wisdom: Long before lab analyses, people recognized that dandelion was a nourishing food. Traditional diets valued it especially in early spring: the young leaves provided one of the first fresh greens after winter, likely supplying much-needed roughage and a small protein boost when other foods were scarce. Many rural folk would say eating dandelion salad or soup gave them “strength” and helped “get your system going” after winter stagnation – an observation consistent with its fiber (aiding bowel regularity) and nutrient content. The slight bitter taste of the leaves was taken as proof of its potency in stimulating appetite and digestion, a concept in traditional European herbalism (bitter flavors signaling the body to release digestive juices, thereby helping one derive more nourishment from all foods). Healers would encourage weak or convalescent individuals to sip dandelion broth for easy nutrition. In frontier times and during wars, people roasted dandelion roots to make dandelion coffee not just for the taste but as a sustaining warm drink, noting that it “sits kindly in the stomach” – possibly due to inulin and gentle starches that can soothe an inflamed gut. Also, farmers observed that animals browsing on dandelion stayed healthy; for instance, cows allowed to eat dandelion-rich pasture gave rich milk, and old farmers believed the plant’s nutrients contributed to more golden butter (dandelion’s beta-carotenes, indeed, could intensify butter color). Thus, experiential wisdom regarded dandelion not as starvation food but as supplemental nutrition: something that, in small amounts, could fortify the diet. Recipe traditions arose like mixing dandelion greens with fatty foods (bacon in salads, or olive oil dressings) – interestingly, modern science shows that a little fat can help absorb fat-soluble vitamins from the greens. Through such practices, traditional people maximized the macronutrient benefits of dandelion as a wild staple.

Emerging Hypotheses / Vibrational Theories: Nutritionists today sometimes speak of “energetics” of food in parallel to macronutrients. In that frame, dandelion is considered a balancing, light yet sustaining food. The emerging concept of wild plants in the diet suggests that wild greens like dandelion, with their higher fiber and phytochemical content, may help reset modern palates and gut flora – acting almost like a “probiotic ally” by feeding beneficial gut bacteria with inulin and fiber. Some holistic nutritionists hypothesize that incorporating wild edibles such as dandelion could improve metabolic health beyond what their calorie content suggests, possibly by signaling the body through bitter receptors to better regulate blood sugar and appetite (a hypothesis under investigation related to bitter compounds and hormones like ghrelin). From a vibrational standpoint, one might say dandelion’s macronutrient gift is its efficiency and vitality: it packs a spectrum of essentials into a low-calorie package, resonating with the idea of “nutrient density” as energy. This subtle property is being explored as we face modern nutrient-poor processed diets – dandelion stands as an old-new answer, hypothesized to bring not just bulk but a kind of living energy to our meals that could revitalize digestion and assimilation overall. While hard science is still examining these ideas (like the gut-brain effects of bitter greens), integrative nutrition embraces dandelion as a food that feeds not only the body’s calories but its regulatory systems – a macronutrient profile in service of holistic balance.

Micronutrients:

Scientific Evidence: Dandelion leaves are a potent source of vitamins and minerals. They are exceptionally high in vitamin K – providing about 778 µg per 100 g, which is ~650% of the recommended Daily Value. This makes dandelion one of the richest green sources of vitamin K, important for blood clotting and bone metabolism. The greens are also rich in vitamin A (mainly as beta-carotene): 100 g of fresh leaves gives over 500 µg vitamin A (RAE), about 56% DV, and over 5800 µg of beta-carotene. Vitamin C is abundant as well: ~35 mg per 100 g (around 39% DV), which historically would have helped prevent scurvy in early spring diets. Dandelion also provides notable amounts of vitamin E (3.4 mg, 23% DV) and moderate B vitamins like B2 (riboflavin 20% DV) and B6 (15% DV). On the mineral side, dandelion shines with calcium (~187 mg/100 g, about 14% DV) and iron (~3.1 mg, 17% DV). It offers a good amount of magnesium (36 mg, 9% DV) and manganese (0.34 mg, 15% DV). Particularly notable is its potassium content – around 397 mg per 100 g (13% DV) – contributing to the diuretic effect (the high potassium helps replenish what might be lost in urine). Dandelion also contains trace minerals like copper and zinc in small amounts, and it has some folate (7% DV) and choline (6% DV). Collectively, these micronutrient levels rival those of cultivated leafy vegetables like spinach and kale, which is remarkable for a wild plant. Research confirms that both leaves and roots accumulate minerals: field trials found dandelion to significantly accumulate calcium, potassium, sulfur, and even the micronutrient molybdenum from soil. This dynamic uptake translates into mineral-dense tissues.

Traditional / Experiential Wisdom: People may not have listed milligrams of iron or vitamin A in the past, but they had empirical knowledge of dandelion’s micronutrient benefits. For example, many traditional cultures regarded dandelion as a “blood tonic” – in plain terms, something that “builds good blood.” This often referred to treating anemia or weakness. Women, in particular, used dandelion remedies after childbirth or during heavy menstruation; unbeknownst to them, the high iron and vitamin C in the plant likely helped improve iron status and energy. The concept of “spring bitters” in European folk medicine – of which dandelion was a prime example – was tied to curing winter sluggishness and skin issues. Likely, the increase in vitamins (especially C and A) from eating fresh dandelion aided in clearing up skin and improving immunity, validating the practice. Country people noted that dandelion eaters rarely got scurvy or rickets, common deficiencies historically. In rural France and Italy, giving children dandelion salad in spring was said to “strengthen the bones” – an intuitive grasp of its calcium content combined with vitamin K (which we now know is critical for bone health). In indigenous practice, the fact that dandelion had a salty, mineral-rich taste when chewed was a sign of its ability to replenish the body. Healers might give a decoction of dandelion root or leaf to someone recovering from a long illness to “restore minerals” – essentially a herbal electrolyte solution thanks to potassium and sodium. The flowers, though not consumed as much, were occasionally brewed into a tea for headaches; some speculate this might be due to their magnesium and manganese content supporting relaxation. Across diverse cultures, a bowl of dandelion greens with some fat (like bacon drippings or ground sesame, depending on region) was recognized as one of the most nutritious dishes available from the wild, often credited with improving eyesight (vitamin A) and “purifying” the blood (likely via its nutrient and antioxidant content). This collective wisdom, refined by taste and results, meant that even when other wild edibles were available, dandelion held a special place as a health-giving green.

Emerging Hypotheses / Vibrational Theories: In modern nutrition therapy, there is a growing interest in “food as medicine”, and dandelion is stepping into that spotlight as a micronutrient powerhouse. Some holistic practitioners refer to it as a natural multivitamin. An emerging hypothesis in regenerative health circles is that the complex of micronutrients in dandelion works synergistically in the body. For example, the combination of vitamin C with iron in the leaf is ideal for iron absorption (nature packaged them together, whereas in supplements they must be combined deliberately). This synergy suggests that consuming dandelion might correct micronutrient imbalances more gently and effectively than isolated pills. Vibrationally, some herbalists speak of “mineral energy” – the subtle effect of a plant that is rich in earth elements. Dandelion, with its deep roots mining the earth, is thought to carry a grounding, strengthening energy that corresponds to its mineral content. One theory is that because dandelion accumulates minerals like calcium, iron, and potassium at levels above what the surrounding soil might suggest, it may also contain co-factors (like phytonutrients) that guide those minerals’ utilization in our bodies. Scientists are indeed investigating phytochemicals that improve mineral bioavailability. So, the hypothesis is that dandelion’s micronutrients are highly bio-accessible – our bodies easily recognize and absorb them, perhaps due to accompanying plant acids or flavonoids that act as chelators. Another emerging area of interest is how wild micronutrient profiles could aid in chronic disease prevention: for instance, epidemiological patterns show populations that consumed bitter wild greens (dandelion among them) had lower rates of certain deficiencies and possibly better metabolic health. This spurs questions like, could reintroducing wild micronutrient-rich foods combat modern micronutrient malnutrition and even lifestyle diseases? While research is early, some functional medicine experts are using dandelion in protocols to support liver detox (requiring lots of vitamins and minerals as co-factors) and to replenish patients low in iron or calcium but who cannot tolerate supplements. The vibrational side adds that because dandelion’s nutrients are derived from resilient growth in varied conditions, they carry an adaptability that can communicate to our cells – teaching our bodies to utilize nutrients under stress. Such ideas remain metaphoric, but they encourage a view of food and herb not just as a sum of parts but as a holistic package engineered by nature. Dandelion’s micronutrient bounty, therefore, is seen not only as numbers on a chart but as an integrated tonic, fine-tuned over millennia, to strengthen and balance the human body in ways we are still uncovering.

Bioactive Compounds:

Scientific Evidence: Beyond basic nutrients, Taraxacum officinale is loaded with diverse phytochemicals that contribute to its medicinal effects. Modern phytochemistry has identified sesquiterpene lactones as one signature group – bitter compounds like taraxacin and taraxacoside concentrated in the roots and leaves. These lactones are thought to stimulate digestion (hence the bitter taste) and have demonstrated anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities in cell studies. Dandelion also contains various triterpenoids and sterols such as taraxasterol, β-sitosterol, stigmasterol, and lupeol. Taraxasterol in particular has garnered attention for anti-inflammatory properties and potential liver-protective effects in research. Another key category is phenolic acids and flavonoids: Dandelion is rich in caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid, chicoric acid, and flavonoids like luteolin, apigenin, quercetin, and chrysoeriol. These compounds are potent antioxidants; for instance, chlorogenic and chicoric acids contribute to dandelion’s observed antioxidant and antidiabetic effects by modulating glucose metabolism and combating oxidative stress in studies. Polysaccharides are another crucial component: the root stores up to 40% of its weight as the fiber inulin, which acts as a prebiotic and also gives dandelion gentle laxative and blood sugar-modulating properties. Inulin and other fructo-oligosaccharides in dandelion root can improve gut microbiota composition, as shown in some animal studies. Dandelion’s leaves and flowers contain carotenoids (giving the yellow color), including lutein and zeaxanthin, which benefit eye health. The plant also yields small amounts of essential oils and saponins that may contribute to its diuretic effect and antimicrobial action. A comprehensive 2023 review summarized that dandelion’s therapeutic potential stems from a “wide range of bioactive compounds, including sesquiterpenoids, phenolics, flavonoids, coumarins, sphingolipids, and more,” collectively yielding antibacterial, antioxidant, and anti-rheumatic activities. To highlight a few specifics: Taraxacum extracts show anti-cancer potential partly via luteolin and luteolin-7-glucoside, which induced cancer cell apoptosis in lab experiments. Meanwhile, taraxasterol and related terpenes have shown liver-protective effects in mice by reducing liver enzymes and inflammation. Such findings validate that dandelion isn’t pharmaceutically bland – it’s a cocktail of active phytochemicals.

Traditional / Experiential Wisdom: Practitioners of old may not have named “chlorogenic acid” or “taraxasterol,” but they had an intuitive grasp of these components through the plant’s taste and effects. The bitter milky sap of dandelion was a key signature in folk medicine – bitterness signaled the presence of those lactones, and healers associated that with stimulating bile flow and detoxification. European apothecaries in the 17th-19th centuries would speak of dandelion’s “active bitter principle (taraxacin)” as the ingredient that “opens the liver’s obstructions,” directly correlating to what we now attribute to sesquiterpene lactones’ choleretic effect (increasing bile secretion). Likewise, the diuretic property was so pronounced that many languages named the plant for it (e.g., pissenlit in French). People surmised there was a “salt” or “spirit” in dandelion that flushed the kidneys – today we understand compounds like potassium salts and caffeic acid derivatives contribute to that diuretic action. Traditional herbalists also used the whole plant synergy: they would combine root and leaf in decoctions to get both soluble fibers and bitters. For instance, a common remedy for a sluggish liver was dandelion root tea – now known to deliver inulin (feeding gut flora and possibly reducing cholesterol) along with taraxasterol (supporting liver metabolism). Doctrine of signatures sometimes guided usage: the bright yellow of the flower and the bile-like bitterness suggested it could treat “yellow” conditions like jaundice – and indeed, dandelion has been used as a jaundice remedy across Eurasia. The sticky white latex of the stem was applied to warts and skin growths, a practice validated somewhat by modern observation that the latex contains compounds that can irritate and potentially dissolve warts (some lactones and enzymes). Moreover, dandelion’s anti-inflammatory and cleansing reputation likely comes from the combined action of flavonoids and phenolics. Herbalists found that compresses of dandelion leaf helped soothe skin eczema or acne; unknown to them, the plant’s antioxidant flavonoids were reducing oxidative stress and inflammation in the skin. Another experiential clue was how dandelion preparations rarely caused side effects and could be taken over long periods – a sign that its complex mixture of compounds is generally gentle and balanced (for example, it provides potassium while acting as a diuretic, preventing the electrolyte depletion that pharmaceutical diuretics can cause). In essence, through careful observation, traditional healers tapped into dandelion’s pharmacopeia of bioactives: using bitters for digestion, poultices for inflammation, teas for kidney and liver health, etc., aligning well with what we know about its phytochemistry today.

Emerging Hypotheses / Vibrational Theories: Current herbal theorists are exploring how dandelion’s bioactive compounds might interact with the body in dynamic ways. One emerging idea is the concept of the “entourage effect” – that the many compounds in dandelion work in concert to produce a greater effect than isolated constituents. For example, while one flavonoid might be a moderate antioxidant, in the presence of others plus vitamins (like A and C in the plant), the total antioxidant capacity is significantly higher. This synergy is being investigated through whole-plant extract studies, some of which show robust anti-cancer or anti-inflammatory results that single compounds don’t fully replicate. From a more esoteric perspective, vibrational herbalism would say dandelion’s diverse chemistry reflects a holistic healing energy – it doesn’t target just one organ or pathway but rather supports the entire terrain of the body (much as the plant itself improves the whole soil ecosystem where it grows). Some hypothesize that dandelion’s compounds even have a selective intelligence, such as potentially inducing apoptosis (cell death) in cancer cells while protecting normal cells. Early lab research provides some support: dandelion root extract induced death in leukemia and melanoma cells but not in healthy cells in vitro, suggesting a nuanced mechanism possibly due to multiple compounds hitting multiple targets. Another emerging hypothesis involves dandelion’s bitter compounds and gut receptors: there’s interest in how lactones like taraxacin might activate bitter taste receptors in the gut and lungs, leading to systemic anti-inflammatory effects (an area of research connecting gut bitter receptors to immune responses). Vibrationally, one could say dandelion “communicates” with the body, tuning various systems towards balance – a poetic way to describe multi-target pharmacology. The concept of plant intelligence finds a case study in dandelion’s latex: recent science noted that the latex contains compounds that protect the plant from insect pests and microbial attacks. Herbalists speculate that when we ingest small amounts of this latex (say from a tincture), it might have an antimicrobial effect in our gut or bloodstream, assisting our immunity akin to how it protects the plant. It’s a hypothesis requiring more study, but it aligns with traditions that used dandelion for infections and blood cleansing. Lastly, in the realm of subtle energy, the variety of bioactive compounds is sometimes likened to musical chords – dandelion’s many chemicals form a “chord” that resonates with the body’s organs (bitters with liver, inulin with pancreas, flavonoids with blood and heart, etc.). While these analogies aren’t testable in a lab, they encourage a comprehensive view: Taraxacum officinale is a sophisticated natural pharmacy, and we are only beginning to decode the full score of its bioactive symphony. This drives a modern hypothesis that re-incorporating such whole-plant medicines into health care could address complex chronic conditions better than single-target drugs, thanks to the multi-faceted interplay of compounds – a very old idea coming full circle with new science.

Medicinal Uses & Clinical Evidence:

Traditional preparations: For centuries, dandelion has been prepared in myriad forms to support health. Teas and infusions are among the oldest methods – steeping the dried leaves or roasted roots in hot water. Traditional Chinese Medicine has used dandelion tea (often combined with other herbs) for over 2,000 years to treat stomach problems, appendicitis, and breast issues like inflammation or lack of milk flow. European folk medicine favored dandelion leaf tea as a “spring tonic” to flush the kidneys and gallbladder; it was common to drink a cup daily for a week or two in spring to “purify blood.” Salves and poultices were another preparation: bruised fresh dandelion leaves or a mash of the roots would be applied to skin – to soothe skin eruptions, insect stings, or even joint pains. Some Indigenous North American remedies included chewing fresh dandelion and placing it on skin to relieve bee stings or nettle rash (the anti-inflammatory and anti-itch effects could be attributed to the plant’s phytochemicals). In Eastern Europe, a dandelion flower oil infusion was made by infusing the yellow flowers in oil under the sun for days; this oil, rich in triterpenes and flavonoids, was then used as a massage oil for sore muscles and arthritic joints, a practice validated by many who feel it alleviates stiffness (perhaps due to mild analgesic compounds in the flowers). Tinctures (alcohol-based extracts) have long been part of Western herbal pharmacopeia: the entire plant or specific parts (root for liver, leaf for kidneys) are soaked in alcohol to extract potent constituents. A dandelion root tincture is a time-honored remedy for liver congestion, sluggish digestion, and skin conditions like acne or eczema, which by lore are tied to “liver heat.” Modern herbalists continue this practice, dosing a few milliliters of tincture before meals to stimulate bile production and appetite. Historically, syrups and wines made from dandelion were also medicinal: dandelion wine, aside from being a country beverage, was taken in small cordial glasses as a digestive and mood uplifter. A honey or sugar syrup of dandelion (sometimes called “dandelion honey” when flowers were cooked with sugar) was used as a cough remedy – the sweet base soothing the throat and dandelion’s compounds providing gentle expectorant and anti-inflammatory effects. These preparations often came with specific seasonal or situational uses: spring for cleansing teas, summer for skin-healing poultices, autumn for harvesting roots to make strong tinctures to store over winter. All of these traditional preparations aim to capture dandelion’s multifaceted medicinal qualities in accessible ways, and many remain in use in folk medicine today.

Modern herbal insights & pharmacological actions: Contemporary research and clinical observations have shed light on how dandelion exerts its effects, often confirming traditional claims. One of the best-known uses – as a diuretic – has scientific backing: a human trial in 2009 found that an extract of fresh dandelion leaf increased urinary frequency and volume significantly for a short term, aligning with centuries of anecdote about “pee-the-bed” properties. Unlike pharmaceutical diuretics, dandelion does this without depleting potassium; in fact, its high K content may actually supplement this electrolyte. Clinically, naturopathic doctors might recommend dandelion leaf tea or tincture for mild hypertension or edema for this reason. Hepatoprotective (liver-protecting) and choleretic (bile-stimulating) actions are another area of modern focus. Animal studies have demonstrated that dandelion root and leaf extracts can protect the liver from toxic insults (like carbon tetrachloride exposure or high-fat diets), resulting in lower liver enzyme levels and less fatty accumulation. This correlates with its traditional use as a liver tonic. Herbalists now incorporate dandelion root in protocols for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease or sluggish gallbladder function, often alongside other herbs. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects have been confirmed in numerous in vitro and in vivo studies: dandelion extracts have been shown to down-regulate pro-inflammatory cytokines (like TNF-α and IL-6) and up-regulate antioxidant defenses. Clinically, this could translate to benefits in inflammatory conditions – for instance, herbal practitioners see improvements in chronic skin issues (acne, psoriasis) when using dandelion internally, likely due to systemic anti-inflammatory effects. Metabolic and endocrine benefits are another modern insight: studies indicate dandelion can improve lipid profiles (one study noted lowered triglycerides and improved HDL in mice on a high-fat diet given dandelion) and might have a mild blood sugar-lowering effect by enhancing pancreatic beta-cell function and increasing insulin sensitivity. While not a primary herb for diabetes, it is often included in supportive formulas. Taraxacum is also being investigated for antiviral and immunomodulatory properties: lab experiments showed dandelion extracts can inhibit influenza and even block binding of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to receptors. In practice, some herbal doctors used dandelion as part of herbal blends during viral infections for its broad immune-supportive role. One burgeoning area is cancer research: remarkable lab results demonstrate dandelion root extract inducing apoptosis in leukemia cells and melanoma cells while sparing normal cells. There’s even a case report of dandelion tea contributing to a remission in a blood cancer patient, though this is anecdotal. The first phases of clinical trials are underway to test dandelion root extract in cancer patients (e.g. in Canada for drug-resistant leukemia), driven by these promising preclinical data. Pharmacologically, these actions are attributed to the synergy of dandelion’s compounds: e.g., luteolin and chicoric acid contribute to anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory pathways by modulating signaling (like NF-κB pathway), while inulin improves gut health, indirectly affecting immune regulation. In modern herbal practice, dandelion is considered a “cholagogue, diuretic, mild laxative, and nutritive”, often recommended for conditions like: water retention, kidney stones (as a flushing agent), poor digestion, constipation (due to its bitter and fiber content), eczema and acne (addressing internal toxic load), and as supportive care in arthritis (via its anti-inflammatory and diuretic action reducing swelling). Commission E (the German herbal regulatory authority) approves dandelion for restoring appetite and treating dyspepsia, reflecting scientific consensus on its digestive benefits. Further clinical evidence comes from integrative medicine: e.g., trials combining dandelion with other herbs found improved outcome in tonsillitis in children, and animal studies suggest it could help in weight management by inhibiting pancreatic lipase (similar to how some obesity drugs work). As these insights grow, more health professionals are embracing dandelion – some functional medicine practitioners even call it “the herbalist’s swiss army knife” for metabolic syndrome, since it addresses multiple facets (inflammation, blood sugar, cholesterol, liver function). Importantly, modern use is informed by both evidence and tradition: for instance, using fresh leaf juice as a diuretic (evidence-backed) or using the root for cancer support (evidence emerging but tradition long-standing for tumors and boils). This integration keeps alive the practical knowledge that a cup of dandelion tea or a dropper of tincture can have measurable, positive impacts on physiology – something both old herbwives and new scientists agree upon.

Case in point: A recent comprehensive review tallied at least 12 distinct medicinal properties of dandelion documented in scientific studies: diuretic, liver-protective, anti-colitis, immune-modulating, antiviral, antifungal, antibacterial, anti-arthritic, anti-diabetic, anti-obesity, antioxidant, and anticancer. The most robust evidence among these is for its antioxidant, hepatoprotective, and anticancer effects. This breadth validates why traditional herbal systems used one plant for so many ailments – dandelion truly has polyvalent actions.

Safety & Contraindications: Dandelion is generally very safe and gentle, especially as a food, but modern understanding highlights a few considerations. Allergies: People with allergies to ragweed or other Asteraceae plants (chamomile, chrysanthemum, etc.) might react to dandelion, since it contains similar allergenic sesquiterpene lactones. Such reactions are rare but can manifest as contact dermatitis (from handling the plant; cases of children getting skin rashes from playing with dandelion stems are recorded) or, in extremely rare cases, mouth/throat itching if eaten raw. Patch tests on sensitive individuals confirm dandelion latex can cause rash – so those known to have plant allergies should introduce it cautiously. Drug Interactions: Because dandelion can act as a diuretic, it may add to the effect of prescribed diuretics (potentially causing excessive water loss or altering blood pressure). It’s wise to monitor blood pressure or electrolytes if someone is taking both. Its blood sugar-lowering tendency could also add to hypoglycemic drugs’ effect, so diabetic patients should use it under guidance and watch blood glucose. One significant interaction is with certain antibiotics or drugs metabolized by the liver: high inulin and flavonoids, dandelion extract can inhibit cytochrome P450 enzymes (notably CYP3A4 and CYP1A2 in some studies). For instance, a kidney transplant patient had elevated levels of immunosuppressant drugs when drinking dandelion tea, suggesting interference with drug metabolism. Though not common, it’s a caution for those on narrow-therapeutic-index meds (like warfarin, where vitamin K content is also an issue; large amounts of dandelion greens could antagonize anticoagulants due to that high vitamin K). Pregnancy and Lactation: Dandelion is food, so moderate use (like occasional teas or salads) is considered safe during pregnancy – in fact, as a gentle source of vitamins and to relieve mild edema. However, very strong doses or tinctures should be taken with care. Traditionally, dandelion was used to promote lactation (it’s a galactagogue in TCM), and some women still drink it postpartum. There’s no evidence of harm, but scientific data are limited, so most sources list dandelion as likely safe in pregnancy/lactation in dietary amounts, with no known risk other than allergy. Digestion: The bitter and high-fiber nature can cause mild stomach upset or heartburn in some individuals, especially if taken in excess or on an empty stomach – basically the digestive juices it stimulates can cause slight discomfort or acid reflux in sensitive people. Starting with small doses can mitigate this. Kidney or gallbladder issues: Because dandelion increases bile flow, those with blocked bile ducts or gallstones should use caution – a strong choleretic like dandelion could precipitate pain or gallstone movement. Similarly, while its diuretic action can help prevent kidney stones, someone with existing kidney disease or stones should consult a doctor before using high amounts, just to ensure it’s appropriate. Notably, some older case literature mentions dandelion leaf might exacerbate heartburn in susceptible individuals (owing to increased stomach acid), and there was a case of a woman developing oxalate crystals in urine (digital necrosis) from consuming 10–15 cups of dandelion tea daily for months – an extremely high intake far beyond normal use, highlighting that “too much of a good thing” can indeed be harmful. Dandelion, like many leafy greens, contains some oxalates, so mega-dosing is discouraged. Regulatory status: In many countries, dandelion is regulated as a dietary supplement or herbal medicine. It’s approved in the Pharmacopoeias of China, Europe, and others, attesting to its recognized safety. That said, labeling must not claim to cure diseases – e.g., in the U.S., one cannot market dandelion products claiming “treats diabetes” without proper approval. Another consideration: Dandelion foraged from lawns can be contaminated by pesticides or animal waste; thus, a safety guideline is always to harvest from clean, chemical-free areas to avoid ingesting pollutants. Summarizing contraindications – avoid high-dose dandelion if: you have known plant allergies, you’re on critical meds like blood thinners (without medical advice), or you have acute biliary obstruction. Use with caution if: on diuretics or diabetic meds (monitoring required), or if pregnant just stick to moderate amounts. For the vast majority, moderate use of dandelion in food or tea form is very well tolerated. In fact, Taraxacum is often praised for its lack of toxicity – it does not damage organs and has an excellent safety profile even at relatively high extracts, as evidenced by traditional long-term use and modern toxicology studies (which find it has a high LD50 in animal models, meaning low acute toxicity). The biggest risk might simply be an upset stomach or a mild rash, which is a small price for its benefits. Thus, dandelion stands as a safe, effective herbal ally when used wisely – but as always, respect the plant’s potency and pay attention to your body’s responses, integrating both traditional cautions and modern findings for the safest experience.

3. Soil & Ecosystem Roles (Ecological, Agricultural, Regenerative)

Soil Building & Nutrient Management:

Scientific Evidence: Dandelions play a notable role as natural soil improvers. Their deep taproots penetrate hard, compacted soils, creating channels that improve aeration and water infiltration. Studies have found dandelion roots can reach depths of over 6 feet (2 m) in loose soils, which helps break up pan layers and loosen the earth. This effectively “drills” into the subsoil, and when the roots eventually decay, they leave behind organic matter deep down and pathways for other roots or earthworms to follow. Dandelion has been identified as a classic dynamic accumulator plant: it draws up nutrients from deeper soil and concentrates them in its tissues. For instance, research funded by SARE (Sustainable Ag Research) showed that dandelion accumulates significant amounts of potassium, calcium, sulfur, and magnesium, often at concentrations far above the average plant – in one analysis, it had a bioaccumulation factor of 36 for K (meaning 36 times the soil concentration) and also above-average levels of Ca and micronutrients like copper and sodium. Another survey of wild plant mineral content confirms that dandelion is rich in iron, phosphorus, and trace minerals as well. When dandelion leaves and roots die or are turned into the soil, these nutrients are released, enriching the topsoil for other plants. Moreover, field observations in regenerative farms note that dandelion growth correlates with improved topsoil crumb structure – likely because their decaying root casts help bind soil aggregates and their presence fosters microbial life. Indeed, some experiments indicate that soils with dandelion have higher microbial biomass and earthworm activity (as worms are attracted to the nutrient-rich, easily decomposed dandelion matter). Dandelion leaves have a low C:N ratio and “low fibrosity” (they break down more easily than, say, grass leaves), which means they compost readily, returning nutrients quickly to the soil. Garden Organic in the UK reports that dandelions are relatively high in nitrogen, calcium, copper, and iron compared to common pasture grasses, and their tissues rot fast in compost. Farmers have empirically noticed that adding dandelions to compost piles can speed up decomposition – possibly due to enzymes or a favorable nutrient balance that “activates” microbial breakdown (hence some call them compost activators). Additionally, the presence of dandelion indicates certain soil conditions: agronomists classify it as a weed of fertile, often neutral to alkaline soils (preferring pH >7), and it often shows up in overgrazed pastures where compaction and nutrient imbalances occur. This indicator aspect means that when dandelions appear in profusion, it’s a clue that soil might be compacted or lacking certain nutrients like calcium (as dandelion thrives in lower Ca, high K conditions). Remediation can involve letting the dandelions grow to do their work, or amending soil (with lime, for example) to shift conditions. Either way, dandelion is actively participating in nutrient cycling: one study noted that dense stands of dandelion could produce up to 97 million seeds per hectare annually; while that’s a weed statistic, think of it conversely – that is a tremendous biomass generation, drawing nutrients from soil and if that biomass is recycled in situ, depositing them back on the surface as a green manure.

Traditional / Experiential Wisdom: Farmers and gardeners have long had a mixed but insightful relationship with dandelions in soil. Traditional European farmers might say, “If you have dandelions, your soil is not all bad,” recognizing that these plants often appear on moderately fertile, workable land (as opposed to extremely acidic or waterlogged soils where they struggle). In small homesteads, people noticed that digging up a dandelion brought up black, friable earth clinging to its roots – a sign that the root was improving the soil texture. Permaculturists and old-time gardeners often refer to dandelion as a “nature’s tiller” or “earth nail” (as it is called in Chinese, referencing the way it nails into the ground). They observed that over a season, a patch of hard ground peppered with dandelions would become easier to dig; the plant literally pries open the soil. This knowledge led to experiential practices: some farmers would intentionally leave dandelions in their fields during initial years of pasture improvement, letting them condition the soil before reseeding with desired crops. As early as the 19th century, it was noted in farming manuals that allowing some “weeds” like dandelion in rotations could be beneficial to soil structure – although they didn’t have the term “dynamic accumulator,” they effectively described the concept. Compost-makers historically included “weeds” like dandelion in their heaps – a 19th century French gardening guide suggests chopping weeds such as dandelion into the compost to “enrich it with potent salts.” Gardeners also made “manure tea” or “weed tea” by fermenting dandelions in water (often with nettles and comfrey) – the resulting brew was a potent liquid fertilizer for plants, indicating those nutrients had leached out into the water. This age-old practice (still used by many organic gardeners) is testament to how valued dandelion’s nutrient content was for feeding crops. There is also a bit of folklore: some farmers claimed that where dandelions grow, the soil is reclaiming its fertility. For instance, on worn-out cropland, the first flush of wild growth often includes dandelion – people took that as a sign the land was healing. In the realm of integration, traditional small-scale farmers often tolerated a certain threshold of dandelions, saying they “keep the soil from going sour.” Interestingly, this might tie to dandelion’s effect of cycling calcium and reducing surface crusting, which could ward off some soil acidification. In stony or thin soils, shepherds noticed dandelions seemed to accumulate soil around them (wind-blown dust catches at the rosette and eventually builds up humus under it), essentially creating little islands of richer soil. All these observations fed into stewardship: experience taught that dandelions are helpers in moderation – too many might compete with crops (so you’d weed some), but having them scattered in an orchard or pasture was seen as beneficial. Farmers also exploited dandelion’s presence for nutrient management indirectly: they’d let animals graze dandelion patches, knowing those animals are essentially harvesting minerals and converting them to manure elsewhere. The dandelion is thereby a connector, pulling deep minerals up for livestock to eat and deposit across the field. Permaculture wisdom today echoes this practice by encouraging letting chickens or foraging animals onto areas with abundant dandelion to naturally spread the wealth. In summary, traditional know-how recognized dandelion as a sign of workable, recoverable land and even as an ally to improve that land, leading to a collaborative approach: using it as green manure, as compost ingredient, or simply as a tolerated co-plant that behind the scenes was fertilizing the soil.

Emerging Hypotheses / Vibrational Theories: In regenerative agriculture and soil science, new theories are developing about how plants like dandelion communicate and manage nutrients in the soil. One emerging idea is the concept of “phytoremediation and mineral mining” on farms: planting or allowing dynamic accumulators such as dandelion to address specific soil deficiencies. Some farmers are experimenting with sowing dandelion intentionally on calcium-poor soils to pull up calcium and then slashing the foliage to mulch in place, effectively using dandelion as a self-driven fertilizer pump. While not common yet (because dandelions usually volunteer on their own), it’s a reversal of mindset that is gaining traction – turning a weed into a cover crop. Another hypothesis under research is that dynamic accumulators not only add nutrients but can mobilize “locked” nutrients. Dandelion roots exude compounds (like certain acids) that might chelate and free up phosphorus or micronutrients that other plants can’t access. There’s evidence that dandelion can increase the availability of phosphorus in pastures by accessing forms of P unavailable to shallow-rooted grasses, and this has sparked interest in multi-species pasture mixes for nutrient cycling. On the vibrational side, some soil healers speak of dandelion’s energetic field strengthening the soil’s life-force. Biodynamic philosophy, for example, posits that dandelion (used in Prep 506) helps the soil “bring in cosmic silica” – practically, this means it’s thought to help soil organisms and plants better regulate the uptake of silica and other elements. Whether or not one believes the cosmic aspect, biodynamic farmers swear that using dandelion preparations yields richer, more structured soil. A subtle hypothesis is that dandelion’s presence might influence soil pH micro-locally by drawing up alkalizing minerals (like calcium and magnesium) – effectively leaving the topsoil slightly sweeter when it decays. Gardeners anecdotally claim that patches formerly thick with dandelion become more favorable to sensitive crops afterwards, as if the soil was “tempered.” From a systems view, emerging agroecology highlights the mycorrhizal and microbial relationships: Dandelion is known to form arbuscular mycorrhizal associations, serving as a host that maintains fungal networks even when main crops are absent (like in a fallow field). One theory is that having dandelions overwinter in a field could preserve mycorrhizal fungi which then rapidly colonize spring crops, boosting their nutrient uptake. This is supported by research noting dandelion as an “overwintering host” for mycorrhiza that benefits subsequent plantings. Additionally, an interesting bio-indicator suggestion is being tested: if dandelion tissues are analyzed, they might reveal what minerals the soil is high or low in (since they concentrate certain ones). This could become a farmer-friendly way to gauge soil fertility by “consulting the weeds.” Vibrationally, the presence of healthy dandelions might also indicate a soil with a balanced energy – neither too acidic nor too waterlogged, but an environment where life forces are active (since dandelion can thrive in human-tended zones). Some regenerative farmers half-joke that dandelions sing to the soil – implying that they stimulate microbial and earthworm activity by providing them good food and habitat. Indeed, a recent observation in a no-till regenerative field was that earthworm castings were often concentrated around the base of dandelion plants, hinting that worms are feeding on their fallen leaves and perhaps cohabiting in the root channels. So one could say dandelion invites the “soil herd” (microbes, worms, insects) to work, setting the stage for richer soil. In conclusion, both measurable science and more abstract theories converge on the understanding that dandelion is a soil caretaker. Far from being just a competitor for crop nutrients, it often adds and redistributes nutrients, improves structure, and fosters an environment where the soil’s living community can thrive – making it a quiet but powerful agent of soil regeneration in the right context.

Biodiversity & Wildlife Support:

Scientific Evidence: Dandelions contribute significantly to farmland and wild ecosystem biodiversity. They are often one of the earliest and longest-blooming flowers in temperate climates, providing a crucial food source for pollinators. Research in the U.K. and US has found that dandelion ranks among the top pollen sources for bees in early spring. One study noted it as the fourth most important pollen source in certain landscapes, after willow, meadowsweet, and blackberry. While dandelion pollen is relatively low in protein compared to some plants (honey bees generally prefer pollen from fruit blossoms when available), studies show that honey bees and native bees readily consume it and benefit from it, especially in early spring or monoculture areas lacking other flowers. Importantly, a 2016 study reported that honey bees feeding on dandelion in spring did not reduce their pollination of neighboring fruit crops – effectively debunking the worry that dandelions distract bees from orchards. In fact, having dandelions in bloom at the same time as fruit trees can increase overall pollinator presence in the area. Beyond bees, dandelions support a variety of insects: at least 93 insect species (including 52 species of Lepidoptera larvae) are documented to feed on or pollinate dandelion. For example, butterfly and moth larvae (such as certain tiger moths and tortrix moths) eat dandelion foliage. The flowers attract hoverflies (Syrphidae), which not only pollinate but whose larvae prey on aphids, thus benefiting pest control. Studies in meadows show that removing dandelions leads to lower abundance of certain beneficial predatory insects, likely because those insects rely on dandelion nectar when prey is scarce. Dandelions also support mycorrhizal fungi networks, linking with species like Glomus and Pythium in the soil, which can indirectly increase plant biodiversity by improving soil fungal diversity. In terms of vertebrates, numerous herbivores utilize dandelion. Scientific observations confirm that domestic livestock like sheep and cattle preferentially graze dandelion where available, due to its palatability and high nutrient content. It’s a “preferred food” for sheep in mountain meadows and readily eaten by cattle on prairie pastures. Wildlife usage is impressive: sharp-tailed grouse in the prairies feed heavily on dandelion flowers in spring (fecal analyses in North Dakota showed up to 96% dandelion content). In Nevada, sage grouse diets in spring are dominated (82%) by dandelion when available, indicating it’s a critical forage plant for these birds post-winter. Deer and elk browse dandelions eagerly in spring and summer – studies in the Rockies show higher deer foraging on sites with abundant dandelion, particularly on disturbed or harvested forest sites where dandelion colonizes. Bears have been documented to eat dandelions: in Yellowstone, grizzly bears consume leaves, stems, and flower heads extensively in June, and in Alberta, black bears target young dandelion growth in spring for its high protein and energy (dandelion constituted a dominant species in spring bear scats). Smaller mammals benefit too – pocket gophers feed on dandelion roots in mountain grasslands, and rabbits and groundhogs commonly nibble the foliage. The seeds of dandelion, though wind-dispersed, end up as food for birds: species like goldfinches, sparrows, and other seed-eating birds will eat the small seeds either directly from the puffball or off the ground. Pigeons and doves have been recorded eating the leaves in winter or early spring when little else is green. Even amphibians and reptiles indirectly benefit – by supporting insect populations that they feed on, and by creating microhabitats (the shade of a dandelion rosette can keep soil moist and cool, aiding earthworms and insects which then feed frogs or lizards). Scientifically, it’s clear that Taraxacum officinale often acts as a keystone food resource during specific seasonal gaps: early spring for pollinators and late spring for certain birds and bears emerging from hibernation. Although one wouldn’t call dandelion a keystone species in the classical sense (ecosystems don’t collapse without it), in human-altered environments it arguably serves a keystone-like function by holding pollinator and herbivore populations when other resources are scarce.