Living Plant Wisdom Profile: Horsetail (Equisetum arvense)

Horsetail (Equisetum arvense) is a living memory of Earth’s deep past—an evergreen whisper from the Paleozoic forests that once blanketed the planet long before flowering plants or humankind appeared. Today this humble, jointed stem still pushes up through riverbanks, orchard rows, and vineyard margins, carrying with it stores of silica, ancestral resilience, and a quiet invitation to remember nature’s original design.

This Living Plant Wisdom Profile is more than a catalog of facts; it is a bridge between worlds: modern science and Indigenous tradition, regenerative farming practice and subtle plant energetics. Within these pages you will find firmly rooted evidence—clinical studies on bone health, field trials on fungal resistance—alongside the experiential wisdom of elders who gathered horsetail at dawn for healing teas and the emerging hypotheses of biodynamic stewards who stir its essence into preparations that fortify entire fields.

May this guide serve you—farmer, herbalist, land steward, or curious life-long learner—as a practical manual and a source of reverent wonder. Let horsetail’s ancient rhythm remind us that true regeneration springs from partnership with living beings who have walked the Earth far longer than we have.

Overview & Botanical Profile

Plant (Scientific Name): Equisetum arvense L. – field or common horsetail.

Common Names: Field horsetail, common horsetail, scouring rush, snakegrass, horsetail fern, mare’s-tail (US/UK), bottle-brush, meadow-pine, pine-grass, foxtail-rush, horse pipes, devil’s guts, and others. (The Latin Equisetum means “horse bristle,” referencing its coarse, jointed stems.)

Family: Equisetaceae (the horsetail family); Equisetum is the only living genus in this ancient lineage (subclass Equisetidae). Horsetails are considered “living fossils” dating back over 300 million years.

Native Range: Circumboreal (circumglobal in northern latitudes). Native to temperate and arctic regions of the Northern Hemisphere – including most of Europe, Asia, and North America (north to ~83°N). It thrives in cool, moist climates and disturbed soils.

Current Global Distribution: Now widespread beyond its native range; introduced in parts of Mexico, South America, Africa and New Zealand. In North America it grows from Alaska (beyond the Arctic Circle) southward to Texas. It is not listed as threatened and is often considered invasive or a weed in many regions.

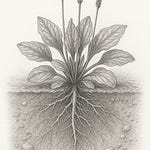

Physical Description: Perennial, non-flowering fern ally with hollow, jointed stems. In spring it sends up brown, spore-bearing (fertile) stems without chlorophyll, 10–25 cm tall. After releasing spores, these die back and are replaced by green, sterile stems 10–90 cm tall (often ~30–40 cm) bearing whorls of needle-like side branches. The stems are rough to the touch due to very high silica deposits in their walls. (See image below.) Stems are photosynthetic, with tightly reduced leaves forming inconspicuous sheaths. The extensive underground rhizome network (often penetrating soil to ~6 feet deep) allows the plant to spread and tolerate diverse conditions.

(Scientific Evidence) Horsetail’s two-part life cycle and morphology: spring’s brown spore cones (white tips) are followed by taller green stems with whorled branches. The stems are impregnated with silica, giving them an abrasive “scouring” texture. These jointed, hollow stems grow from a deep rhizomatous root, making horsetail exceptionally persistent.

1. Cultural Wisdom (Ethnobotany, Mythology, TEK)

Global Traditions:

Historical and Indigenous usage (medicine, food, ceremony): (b) Native American tribes (e.g. Iroquois) used horsetail herb to alleviate headaches, bleeding and bone ailments; it has been employed for wound poultices, diuresis (kidney/bladder cleansing), and as a general tonic. Traditional European herbalists (since Roman/Greek times) used it to stop bleeding, heal ulcers/wounds, and relieve lung and kidney issues. (a) Modern science confirms horsetail’s use as a diuretic and source of silica (a micronutrient for bone/skin). (c) Some esoteric traditions ascribe horsetail protective and energizing qualities, using it in rituals for strength and purification, though these uses lie outside mainstream science.

Integration into agricultural and seasonal cycles: (b) In traditional agrarian calendars, horsetail signals spring and moist soil conditions; spring shoots were harvested (often around full moon or May) to make tonics and preserved for year-round use. (a) Scientifically, fertile stems appear early in spring before green growth, providing one of the first available herb harvests. (c) In biodynamic gardening, horsetail’s lunar/sun influences are invoked (e.g. harvesting under specific moon phases) as part of rhythmic planting wisdom.

Mythology & Symbolism: (b) Folk traditions admire horsetail for its resilience and fertility. It has symbolized strength and durability (e.g. “resilience,” “longevity,” “vitality” in various folklores). Its bristly, tail-like appearance connects it to horse symbolism, and some cultures honor it as a talisman to ward off harm. (a) Practically, its name means “horse tail,” reflecting its bristly form. (c) Spiritually, some herbalists believe horsetail “rejuvenates” subtle energies and use it in essences or charms for protection or resolve, although such interpretations remain largely anecdotal.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK): (b) Many indigenous cultures recognize horsetail’s role in wetlands and riparian areas. They observed it as a soil stabilizer and water indicator, often using it in stewardship of waterways. For example, tribes have used horsetail as a cleansing agent in purification ceremonies (Japanese tea rituals with horsetail for utensil purification; North American rites linking it to water purification). (a) Ecologically, horsetail does stabilize soil and regulate moisture – its deep roots and spreading habit bind banks and pump nutrients upward. (c) Its long memory as an ancient plant invites metaphoric “listening” and reciprocity with the land in some holistic land-care philosophies.

Cultural Disruption & Rematriation: (b) Colonialism and modern development have often displaced horsetail-rich habitats and their cultural use. For instance, traditional gathering sites have been lost to construction and agriculture. This disruption means some communities have limited access to this medicine and experience a loss of related knowledge. (c) Efforts to “rematriate” the plant involve habitat restoration, re-establishing wetlands, and sharing indigenous stewardship practices to ensure horsetail populations (and associated traditional knowledge) continue.

2. Nutritional Profile & Health Benefits

Macronutrients: (a) Horsetail is primarily valued for minerals and phytonutrients rather than macronutrients. The sterile stems have roughly 10–14% protein and some fiber when dried, but very low fat. It provides modest carbohydrates (mostly as roughage) and small amounts of protein (some amino acids). (b) In folk use, it’s not eaten as a food crop; instead its “nutritional” value is seen in its richness in minerals and silica, not calories.

Micronutrients: (a) A standout is its silica content – up to ~25–60% of dry weight. Horsetail accumulates silica in stems, which correlates with its bone-health effects. It also contains vitamins (notably vitamin C and B1), and trace minerals: potassium, calcium, manganese, iron, sulfur, magnesium, zinc, chromium, selenium and phosphorus. (b) Indigenous practices recognize its mineral load: for example, using it as a tonic for bone and connective tissue health (attributed to its silica).

Bioactive Compounds: (a) Rich in antioxidants (flavonoids like quercetin, kaempferol, luteolin, apigenin, etc.), phenolic acids and phytosterols. Contains the alkaloid equisetine (a thiaminase enzyme). (b) Traditional herbalists note its astringent tannins and healing mucilage; (c) some modern authors attribute anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial effects to its phytochemicals, though clinical evidence is limited. Importantly, the thiaminase can deplete vitamin B1, especially if fed to animals or overused in humans.

Medicinal Uses & Clinical Evidence:

Traditional Preparations: (b) Horsetail has long been made into tea, tinctures, infusions, and poultices. Fresh or dried stems are steeped as a tea for kidney/bladder support and as a general tonic. Aided by legends, elders prepared concentrated succus (fresh plant juice) or alcohol tinctures (e.g. brandy macerated with spring shoots) for bone and wound healing. Topically, poultices of crushed stems or infused oils were used on wounds and inflammations to staunch bleeding. (a) Modern herbal medicine still uses horsetail preparations (mainly sterile-stem extracts) as diuretics (for urinary tract disorders) and as silica supplements for bone/skin. Laboratory and animal studies show horsetail extract inhibits bone resorption and stimulates bone formation, supporting its traditional use in osteoporosis and wound healing. (b) Clinically, it’s applied in folk medicine for urinary stones, cystitis, arthritis and skin conditions, consistent with its diuretic and anti-inflammatory reputation. (c) Emerging theories propose horsetail essences or vibrational remedies for “root strengthening,” but these lack scientific validation.

Safety & Contraindications: (a) Horsetail is generally safe in moderate, short-term use as tea or extract. However, its thiaminase activity means long-term use can cause vitamin B1 (thiamine) deficiency; potassium supplementation may be needed if used as a diuretic. It can increase bleeding risk (anticoagulant effect) and blood pressure, so caution is advised in people with hemorrhagic conditions or hypertension. (b) In folk wisdom, one limits a horsetail cure to ~2 weeks on, 1 week off. (a) High consumption has caused toxicosis in grazing livestock (horses especially) due to thiaminase, so it’s unsuitable as forage. (c) There are no major regulatory prohibitions for culinary/herbal use, but quality control is essential to avoid contaminants (heavy metals accumulate in horsetail).

3. Soil & Ecosystem Roles (Ecological, Agricultural, Regenerative)

Soil Building & Nutrient Management: (a) Horsetail rhizomes and deep roots pump nutrients from groundwater up into biomass. Field observations show E. arvense actively transports phosphorus, potassium and calcium from wet subsoil to the surface, enriching riparian soils. As the plant dies back, its silica-rich ash remains, gradually increasing soil mineral reserves. (b) Permaculturists use chopped horsetail as a compost activator or mineral additive; this is traditional knowledge based on its mineral content. (a) Its rhizome network also aerates soil, and decaying stems add organic matter (though high silica means slower decomposition). (c) Quantum-biology speculations suggest horsetail may interact with soil microbes via subtle energetic signals, but this remains unstudied.

Biodiversity & Wildlife Support: (a) Horsetail stands provide cover and habitat in wetlands and disturbed areas. Its presence often indicates moist, undisturbed soils (an ecological indicator). It stabilizes banks and offers microhabitats for invertebrates and amphibians. (b) Some traditional agroecosystems tolerated horsetail as a sign of healthy low-nitrogen soil, using its stems in cattle bedding or fodder sparingly (local knowledge). While not a palatable forage (toxic to many animals), occasional grazing by insects (sawfly larvae, certain beetles) or use as occasional feed (goats, sheep) have been noted. (c) It does not flower, so no pollinators rely on it, but its archetypal presence links prehistoric biodiversity (as a descendant of Paleozoic flora) to current ecosystems.

Succession & Ecosystem Stabilization: (a) Horsetail is a pioneer species on disturbed, especially wet sites. It tolerates flooding and poor soils, often colonizing newly deposited riverbanks and dunes. Studies in Great Lakes regions found E. arvense among the first plants to stabilize eroded bluffs. Its extensive roots hold soil in place and prevent erosion during heavy rains. (a) In forests, horsetail can appear in open understory after disturbances, contributing to groundcover. (c) Some biodynamic farmers believe horsetail “early spring emergence” sends signals of regeneration to the ecosystem, but this is a philosophical interpretation.

Companion Planting & Pest Management: (a) Horsetail is not typically a mutualistic companion (it’s more often a tough weed). However, its silica-rich foliage deters fungal pathogens when used as a spray. Gardeners find that adding horsetail tea to foliar sprays can help suppress powdery mildew and rust on susceptible crops. (a) It is used as a biodynamic preparation (BD #508) specifically for fungal disease prevention. (b) In traditional polycultures, horsetail was sometimes tolerated near damp fruit trees to help keep humidity-regime balance or provide mulch. (c) There’s an emerging idea that growing horsetail near potted plants infuses them with subtle “silica energy,” but this remains conjectural.

4. Bioenergetic Field (Quantum Biology & Vibrational Roles)

Energetic Signature (Flower Essences, Biodynamic Uses): (c) In biodynamic agriculture horsetail is the basis of Preparation 508, a fermented field spray used to strengthen plant immune response. It is applied to fields (in very dilute form) to build resistance to fungal diseases. (a) Scientifically, the active agent is silica (as soluble mono-silicic acid) which fortifies plant cell walls. (c) Herbalists also use horsetail flower essences or homeopathic tinctures, attributing to it a vibration of resilience and purification (though these effects are beyond current scientific validation).

Quantum Biological Hypotheses (Light, Electromagnetic Fields): (c) Some propose horsetail’s high silica might interact with light (e.g. UV capture by silica bodies) or terrestrial electromagnetic fields, hypothesizing that it tunes into earth energies. This is speculative; no empirical studies exist on horsetail electromagnetic biofields.

Microbial & Energetic Signaling: (c) A novel theory suggests plants communicate via light or bioelectrical signals in the soil. Horsetail’s robust microbial associations (especially with wetland fungi and bacteria) hint that it could partake in such networks. For example, fermenting horsetail releases nutrients for microbes, which may “train” a field’s microbiome. (a) Practically, we know fermented horsetail tea promotes beneficial soil bacteria (e.g. Lactobacilli, Bacilli), enhancing plant-microbe signaling in the rhizosphere.

Hypothetical Field Effects: (c) In some land-based spiritual traditions, horsetail’s persistence and ancient lineage make it a symbol of regenerative energy. It is sometimes used in permaculture ceremonies (for example, tossing horsetail tea into wells for “water memory”). These ideas are part of a vibrational worldview and not established by science.

5. Animal Nutrition & Veterinary Applications

Animal Benefits & Uses: (a) Horsetail is not a common feed, due to its thiaminase content. It is generally toxic to grazing livestock (especially horses) if consumed in quantity. (b) However, in ethnoveterinary practice, diluted horsetail extracts have been used externally: for example, farmers have bath-treated hoof rot in cattle or horses with horsetail infusion (recognizing its antifungal effect). (a) Its silica can benefit laying hens (as a natural source of minerals for eggshell strength, though this is experimental use). (c) In homeopathic tradition, very dilute horsetail is sometimes given as a remedy for urinary problems in animals, but again evidence is anecdotal.

Preparations/Methods: (a) A common remedy is an Equisetum tea or decoction (dried stems boiled and cooled) used as a foot soak for hoof infections. (b) In small-scale farming, ground horsetail stem powder can be sprinkled in stalls to absorb moisture (akin to diatomaceous earth) and prevent mold. (c) A vibrational approach is to “etch” silverware with horsetail juice for use in livestock feeding bowls, an esoteric practice believed to impart energetic properties (no scientific data).

6. Practical Regenerative Applications (Hands-On Systems)

Garden Applications:

FPJ/FPE Recipes & Application: (a) Fermented horsetail tea (Biodynamic Preparation 508) is made by filling a container with fresh horsetail, covering with water and fermenting ~10–14 days. The resulting brew (diluted ~1:10–1:20) is applied as a foliar spray to prevent fungal diseases. (b) A quick hot-water infusion can also be used: for example, simmer 1 cup dried horsetail in 4 cups water for 10 minutes, cool and spray on plants to combat powdery mildew. (c) Some gardeners incorporate raw horsetail into botanical compost extracts (adding molasses and fermenting for beneficial microbes, per Korean Natural Farming) to capture its minerals.

Compost Activation & Mulch Usage: (b) Crushed horsetail stems can be added to compost piles or the garden as a mineral-rich mulch. (a) Its silica and micronutrients enrich the compost; additionally, as a fibrous biomass it helps retain moisture in soil. (c) Traditional organic practices once held that leaving some horsetail around rejuvenates the soil for the following crop, a belief now being re-examined scientifically.

Companion Planting Guidelines & Seasonal Timing: (b) Horsetail tolerates full sun to shade. It should not crowd out favored crops, so manage it by shallow digging or shading with mulch/nitrogen-rich cover crops. (a) For beneficial use, thin patches at crop planting time; spray companion plants with horsetail tea at the first sign of mildew. (c) Harvest sterile stems in late spring/early summer when silica is highest (e.g. 8–10 inches tall in May–June) for preparations.

Orchard Applications:

Guild Formation & Pest Management: (b) Horsetail is not typically used in fruit-tree guilds, but its presence in orchards can be leveraged. For example, a ground spray of horsetail tea (BD 508) can protect young fruit trees from blights and fungal spots. (a) Its silica boost may harden leaves of roses and orchard trees, helping them resist pests. (c) Anecdotally, some fruit growers tuck horsetail fronds near tree roots at bloom to “stabilize” the energy of the orchard.

Soil Improvement Strategies: (a) In low-fertility orchard soils, introducing horsetail is generally discouraged; rather, soil should be remineralized through compost and cover crops. However, composting horsetail trimmings from a moist site can recycle its minerals back into the orchard. (b) Historically, orchard keepers might incorporate small horsetail cuts into manure to enrich it.

Water Dynamics Integration: (a) Because horsetail thrives in wet ground, its presence signals irrigation needs. Strategically, planting drainage-grass or clover can manage moisture, leaving horsetail in wetter orchard corners as a natural wetland indicator. (c) Some agroforestry planners use horsetail in constructed wetlands to purify runoff from orchards, leveraging its nutrient uptake and fungal-filtering traits.

Vineyard Applications:

Mid-row Planting Benefits: (b) While not a common cover crop, horsetail can be allowed to grow between vine rows in very wet sites, stabilizing soil. It competes for moisture, so it must be managed. (a) Row sprays of horsetail tea (especially the biodynamic fermented preparation) are valued in organic viticulture; they are applied shortly before budbreak and during the growing season to suppress powdery and downy mildews.

Disease Management Roles: (a) Scientific trials show horsetail-derived formulations (often combined with reduced sulfur) dramatically cut grape mildew incidence. In one Italian study, foliar applications of E. arvense extract plus sulfur resulted in virtually 0% powdery mildew on treated vines versus ~40–60% on untreated controls. This confirms biodynamic vintners’ practice of using horsetail tea as a preventive fungicide.

Applications in Low-Vigor Zones: (a) Horsetail can colonize vineyard corners with poor fertility or poor drainage. In such spots it may persist and even suppress vine vigor. (b) Some growers harvest horsetail from these low-vigor spots for making spray teas, turning a weed problem into a fertility treatment. (c) There is emerging interest in using horsetail root extracts as a potential soil inoculant to improve stressed soils, though research is preliminary.

7. Emerging & Underexplored Applications

Novel Medicinal & Nutraceutical Potentials: (c) Recent research explores horsetail’s antioxidants (flavonoids) for potential anti-inflammatory and anti-diabetic nutraceuticals. Its silica is being extracted for use in bone-health supplements and beauty products (for hair, skin, nails). (a) Laboratory studies suggest antibacterial, antiviral or anti-cancer compounds may be present (e.g. oleanolic and betulinic acids), but human trials are lacking. (c) Seed companies are investigating horsetail genetic diversity for climate resilience traits and niche health-crop development.

Innovative Agricultural Applications: (c) Equisetum’s silica-rich biomass is under study as a natural fungicide/fertilizer pellet (akin to biochar). Its extracts might be developed into biodegradable crop protection products. (a) Because it bioaccumulates metals, it could be used in phytoremediation of polluted soils or water (an aspect of soil management and climate adaptation). (c) Some innovators are testing horsetail fibers for growing media or erosion-control mats.

Sustainable Industrial & Craft Opportunities: (c) Traditionally, horsetail stems were used to polish metal and wood; modern artisans experiment with them as natural scourers or in herbal crafts (e.g. homemade pot-scrubbers or brushes). (a) The plant’s high silica content makes its ash a potential raw material for specialty glazes or cement additives. (b) Ethnobotanists note its dye potential: boiled stems yield a green-gray dye for textiles. (c) Emerging crafts include distilled horsetail eau de vie (inspired by other botanicals) and horsetail-infused salves or beers.

Climate Resilience & Carbon Farming Potentials: (a) Horsetail’s deep rhizomes store carbon belowground, and its perennial growth contributes to long-term soil carbon, aiding carbon farming. (b) Its tolerance of saline or drought-stressed soils (e.g. coastal dunes) makes it useful in climate-adaptation planting for land stabilization. (c) Some carbon farming strategists propose planting horsetail in riparian buffers to sequester nutrients and protect waterways under climate change. Its role as a stabilizer and nutrient-pumper aligns with agroecological climate resilience models.

8. Practical Applications & Revenue Streams (Farmstead Perspective)

Raw & Minimally Processed Products: Horsetail can be marketed fresh (spring shoots for niche culinary uses) or dried for teas and supplements. (a) Dried horsetail herb is sold as a medicinal tea or capsule for bone and urinary health (reflecting its silica/diuretic uses). (b) Freeze-dried or powdered sterile stems could be labeled as a trace-mineral supplement (e.g. “silica powder” for gardeners or herbalists). (c) Some small farms are developing horsetail sap (succus) as a concentrated herbal tonic – a craft product sold by the ounce.

Living Fertilizer Line: (a) A farm could produce Horsetail FPJ (fermented plant juice) or FPE (fermented plant extract) as part of a natural fertilizer line. These liquid products harness the plant’s silica and nutrients for foliar sprays. (b) Custom soil amendments might include compost teas enriched with horsetail or rock powders to simulate its mineral profile. (c) These living fertilizers can be marketed as organic, biodynamic, or regenerative inputs, especially to high-value orchards and vineyards.

Animal-Related Products: (b) Value-added horse/pet care items: for example, dried horsetail in hoof powder blends to help prevent hoof fungal infections (leveraging its traditional hoof-rot remedy). (b) Handmade herbal wound salves or liniments containing horsetail extract can be offered for livestock and pets (playing on its styptic and astringent reputation). (a) As noted, care is needed to label that it is for external use only (to avoid thiamine-deficiency in animals).

Craft & Value-Added Goods: (c) Edible/Hospitality: Horsetail-flavored spirits or bitters (like herbal vodka infusions) are experimental crafts. (b) Natural dyes: craft kits for “plant dyeing” may include horsetail for green-gray shades. (b) Fiber crafts: dried stems (buffered of silica) might be woven into rustic wreaths or natural brushes. (c) Biochar or ash from horsetail can be sold for ceramics/glazing or soil remineralization projects.

Agritourism & Educational Offerings: (b) Farms can host workshops on herbal medicine making, featuring horsetail identification and preparation. (c) Guided “forage & use” tours focusing on wetland plants can include horsetail ecology and crafting. (a) Educational materials could tie in science: e.g., demonstrating silica uptake or microbial activity in horsetail ferments (appealing to agriscience enthusiasts).

Seed & Plant Commerce: Equisetum arvense does not produce true seeds, but plant materials can still be sold. (b) Nurseries might offer horsetail rhizome divisions or live potted plants (noting its invasive potential). (a) While not seed-propagated, spores can be a novelty product for educational kits on plant life cycles. (c) Emphasis on Equisetum “stewardship stock” (sustainably harvested starter clumps) could be part of a native-plant nursery niche.

9. Practical Set-Up Timeline

Season Activities & Recommendations

Spring

(b) Harvest: Collect early fertile shoots (just emerging) for medicinal tinctures or teas; leave majority of plant to grow. (a) Soil: Prepare sites where horsetail will be managed or encouraged (e.g. shady, moist ground); apply fermented horsetail tea to saplings and seedlings to boost resistance (especially at bud break). (c) Planting: Sow any companion cover crops; note horsetail’s spore release means wet patches may seed more horsetail.

Summer

(a) Maintenance: Apply compost tea or FPJ (including horsetail tea) during the growing season to soil and as foliar spray, targeting fungal pests. (b) Use: Harvest additional sterile stems for drying (tea/herb uses) or fermenting. (c) Control: Mow or pull horsetail from unwanted areas; transplant clumps to intended garden spots.

Autumn (Fall)

(b) Clean-up: After frost kills back the stems, cut plants down; compost or dry stems for winter use (silica residue remains). (a) Soil: Incorporate chopped decayed horsetail into compost piles to enrich minerals for next spring. (c) Preparation: Begin brewing winter’s stock of horsetail tincture (e.g. soak spring harvest in alcohol).

Winter

(b) Reflection: Plan garden layout incorporating horsetail knowledge; share practices with community. (a) Processing: Continue fermentations (FPJ/FPE) started in late autumn; filter and store for early spring use. (c) Education: Update research on E. arvense, design any experiments for next season (e.g. test its effect on seed germination or soil tests).

10. Compliance & Safety Notes

Harvesting Guidelines: Collect aboveground sterile stems (green portion) rather than roots or older plant material, to avoid excess alkaloids. Harvest sustainably: take only a portion of any patch, and disturb soil minimally (horsetail roots regenerate rapidly). Avoid polluted sites, as horsetail bioaccumulates heavy metals (it’s used as a bioindicator for soil toxins).

Food Safety & Handling: Handle fresh horsetail gently – wash thoroughly to remove sediment and insects. Dry clean or batch-boil to reduce thiaminase activity before consumption. Label herbal products clearly (e.g. “for external or limited internal use”). Keep horsetail-based food/drink away from infants and those with nutrient deficiencies unless professionally guided.

Regulatory Considerations: In most regions horsetail is unregulated as an herbal ingredient, but marketed supplements should comply with local herbal product rules (e.g. labeling of contraindications). Note that in New Zealand and some Pacific islands horsetail is listed as an invasive species, so its cultivation may be controlled there. Always ensure organic or sustainable certification if advertising ecological claims (since horsetail’s weed status can conflict with “crop” status). If used as a pesticide substitute, it may be exempt or limited by organic standards.

11. Experimental Designs & Farmer-Science

Experiment: Effect of Horsetail Tea on Powdery Mildew in Cucurbits – Compare untreated squash vs. squash sprayed weekly with fermented horsetail tea.

Design & Methodology: Use randomized block design in a home garden or farm plot. Apply horsetail tea (BD 508 style, 1:10 dilution) to treatment plants, water-only to controls. Ensure equal sun/water conditions.

Metrics & Tools Needed: Assess disease severity (% leaf area infected) with a simple rating scale weekly. Measure yield (fruit count/weight) and plant vigor. Record soil moisture and nutrient levels (basic soil test kit) to check any nutrient differences. Use a refractometer or silica test on leaves to detect silicon uptake. Data collection over 8–12 weeks.

Another idea: Horsetail Soil Amendment Trial – Compare plots with horsetail-added compost vs. standard compost. Measure soil structure (percolation test), nutrient levels, and crop growth.

Experiment: Bone Health in Poultry Supplemented with Equisetum – Following the Tufarelli study, repeat with local hens.

Design: Two groups of hens, one fed normal feed, the other supplemented with 1% horsetail powder in feed.

Metrics: Eggshell thickness (micrometer), calcium content in eggshell (ICP or chemical assay), hen health indices. Required tools: caliper, basic lab (or send samples to extension lab), production records.

12. Wisdom Carried Forward (Reciprocity, Ethics, Stewardship)

Ethical Relationship & Reciprocity: Honor horsetail as a healer and helper. In practice, this means harvesting mindfully (gratitude offerings, e.g. a libation of water or tea returned to earth) and never taking the whole patch. (b) Many herbalists teach giving thanks or prayers to plant spirits before harvesting, asking permission for its gift. (c) Practitioners also sometimes “biodynamize” horsetail preparations with a blessing or intention to amplify its benefit.

Cultural Restoration & Seed Sovereignty: Recognize the role of indigenous and folk traditions in keeping horsetail knowledge alive. Support seed sovereignty by exchanging Equisetum rhizomes freely (since it cannot be patented) and including it in heirloom medicinal gardens. (b) In areas where native peoples used horsetail, encourage community medicine-making programs to restore its traditional uses. (c) Promote the idea of “wildcrafting reciprocity” – e.g., for every section of horsetail harvested, propagate another piece nearby to ensure continuous lineage.

Personal Reflection & Intuitive Insights: Horsetail teaches patience and persistence; it reminds us that some of the oldest wisdom comes from humble plants. Growers might journal about lessons from horsetail (its cycles, resilience) to inform their own regenerative practices. (a) Practically, gardeners note that even when horsetail seems invasive, it signals something important about the land (wetness, mineral balance). Balancing its role – as both a garden ally and a weed – offers insights into working with nature’s rhythms rather than against them.

13. Reflection & Wisdom Insights

Horsetail embodies resilience and renewal, bridging ancient ecosystems and modern cultivation. It offers the tangible gift of silica and healing compounds (scientifically validated) while inspiring respect for nature’s tenacity. “As the plant whispers through its silicon threads, we learn of strength and healing,” is how some stewards describe its energy.

Practically, key takeaways include: (a) harness horsetail’s minerals through teas and compost to strengthen soils and plants; (b) employ it judiciously as a natural fungicide; (c) approach it with reverence as both a persistent weed and a valuable medicinal herb. Its life cycle reminds us that adaptation (spring spores to summer green) and patience (rhizomes deepening) are central to ecological wisdom. Embracing horsetail in the landscape and farm is to honor a lineage stretching back to Earth’s Carboniferous past, applying that legacy to regenerate our future.

Bibliography & References

Scientific Sources: Peer-reviewed studies on Equisetum arvense (e.g. bone density studies; agronomy trials), botanical texts and extension articles, modern phytochemical analyses.

Ethnobotanical & Indigenous Knowledge: Published ethnographies and traditional medicine sources (e.g. Densmore, Herrick, archival texts; Native American herbal compendia), plus oral histories (as collected in folk journals and organic farming newsletters).

Agricultural Resources: Organic/farm guides and biodynamic literature (e.g. Biodynamic Preparations manuals, regenerative gardening articles), plus government plant databases (USDA Forest Service; state extension publications). These have been cited inline as shown.

Share this post