Burdock (Arctium minus) – Comprehensive Living Plant Wisdom Profile

Introduction

In a world eager for quick fixes and pharmaceutical promises, the humble burdock root stands as a quiet elder — thorny yet healing, ancient yet deeply relevant. What looks like a common weed is, in truth, a plant ally revered by healers, farmers, and mystics across generations and continents.

Burdock (Arctium tomentosum) carries a multidimensional wisdom: from its detoxifying roots that nourish the blood and liver, to its burrs that inspired Velcro, to its mythic presence in folklore and ritual.

This guide is not meant to tell you what to do with burdock — it’s here to spark your curiosity. Whether you're a regenerative farmer, a wildcrafter, a healer, or a seeker of ancestral connection, what follows is a layered exploration. Each section offers a new lens: scientific, cultural, energetic, and deeply practical.

Let this journey ground you in relationship — to plant, to place, and to the subtle wisdom woven through nature’s design.

Table of Contents

Cultural Wisdom (Ethnobotany, Mythology, TEK)

Indigenous, folk, and spiritual relationships with burdock.Nutritional Profile & Health Benefits

Macronutrients, micronutrients, and therapeutic potential.Soil & Ecosystem Roles (Ecological, Agricultural, Regenerative)

Soil indicators, phytoremediation, and pollinator support.Bioenergetic Field (Quantum Biology & Vibrational Roles)

Lunar timing, vibrational resonance, and plant consciousness.Animal Nutrition & Veterinary Applications

Uses in livestock care, wildlife support, and animal wellness.Practical Regenerative Applications (Hands-On Systems)

Intercropping, dynamic accumulators, and companion planting.Harvesting, Processing & Storage Tips

Techniques for root digging, burr removal, drying, and fermenting.For Subscribers only past this point

only $5 a month to support this research :)

Culinary & Daily Use Recipes

Broths, stir-fries, burdock pickles, and herbal tea blends.Fermentation & Herbal Formulations

FPJ/FPE recipes, tinctures, syrups, oxymels, and poultices.Testing & Research Ideas

DIY field trials, nutrient cycling, and microbial observations.Potential Market & Community Applications

Herbal products, regenerative storytelling, and education models.Plant Communication, Myth, and Ceremony

Dreamwork, ritual, symbolic meaning, and intuitive connection.Closing Reflections & Personal Integration

Weaving knowledge into practice and forming deeper relationships.

Overview & Botanical Profile

Plant: Arctium minus (Hill) Bernh., commonly known as common burdock or lesser burdock. It is a biennial herbaceous plant in the Asteraceae (daisy) family. Burdock is native to Europe and parts of Asia (including the Middle East and North Africa). It was accidentally introduced to North America, where it’s now widespread across most of the continent (present in nearly all U.S. states and Canadian provinces). In many regions it is considered an invasive or noxious weed due to its aggressive growth and prolific seeding.

Common Names: Common burdock, lesser burdock, bardane (French). Folkloric names include beggar’s buttons, clot-bur, sticky back, and Happy Major. In Japanese cuisine the root is known as gobo, and it has been traditionally used as a vegetable. These diverse names reflect the plant’s clinging burs and its global presence (Europe, Asia, and the Americas).

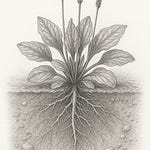

Physical Description: Arctium minus in its first year forms a low rosette of large, heart-shaped leaves up to 30–60 cm long. The leaves are deep green above and whitish downy beneath, with long fleshy petioles that have a reddish tinge. In the second year, the plant bolts a coarse branched stem 1–2 m tall (3–6+ feet). It bears round, thistle-like flower heads that are purple (occasionally pink or white), about 1.5–2.5 cm across, composed of many tubular florets. Each flower head is encircled by a bur-like involucre of hooked bracts. When mature, these dry into the familiar burs that easily latch onto fur and clothing, serving as the seed dispersal mechanism. The burs contain dark, ridged seeds (achenes) ~5–6 mm long. Burdock’s taproot is thick and deep (often 30–90 cm or more in loose soil), brown on the outside and whitish within. The root of first-year plants is fleshy (like a slender parsnip) and stores nutrients (notably inulin), whereas second-year roots become woody as the plant flowers.

(Scientific Evidence:) Botanists note that a single burdock plant can produce up to 15,000 seeds, and those seeds can remain viable in soil for years. This, combined with the tenacious taproot, makes established burdock patches hard to eradicate. The hooked burs famously inspired the invention of Velcro: in 1941 a Swiss engineer, George de Mestral, examined burdock burrs sticking to his dog’s fur under a microscope and realized their hook-and-loop design could be mimicked in a fastener. This biomimicry story highlights burdock’s unique place at the intersection of nature and technology.

1. Cultural Wisdom (Ethnobotany, Mythology, TEK)

Global Traditions:

Traditional / Experiential Wisdom: Burdock has been respected in folk medicine across many cultures. Historical records from Europe (since the Middle Ages) praise burdock for its “blood-cleansing” and detoxifying properties. European herbalists brewed burdock root tonics to purify the blood and used the root or seeds for ailments like arthritis, gout, kidney stones, and skin conditions. In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), burdock (especially the seeds, called niúbàngzĭ) is used to expel “toxins” and treat sore throats, colds, and rashes by dispersing wind-heat. The roots and leaves in TCM are considered nutritive and are used to “cool” and detoxify the blood, often to improve skin health (e.g. eczema, acne). In Japan and Korea, burdock root (gobo) is a common vegetable; beyond its nutritional value it is believed to build strength and vitality. A Japanese folk adage claims burdock supports longevity, and gobo soup has been traditionally recommended to “prevent cancer, cure diabetes, lower blood pressure, and even cure hangovers” (reflecting folk observations of its health benefits). Across South and East Asia, the plant’s tonic and anti-inflammatory properties have been integrated into healing systems for centuries.

Burdock’s use as a healing food and medicine spans the globe: ancient Greek physicians, Ayurvedic practitioners in India, and healers in the Middle East all found uses for it. In fact, burdock’s reputation as a “universal purifier” appears in disparate cultures. Scientific Evidence: Modern ethnopharmacology notes that many of burdock’s traditional uses have biochemical basis – for example, its diuretic action (noted by European folk healers) helps the body eliminate wastes, aligning with the “blood purification” concept. Also, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory compounds in the plant give credence to its use for arthritis and skin diseases.

Indigenous North America: Traditional Wisdom: Although burdock is introduced to the Americas, many First Nations and Native Indigenous tribes adopted it into their healing repertoire. Ethnobotanical records show at least 14 tribes used burdock medicinally. For instance, the Chippewa (Ojibwe) made a cough medicine from burdock leaves and used an infusion of the root for stomach pain. The Meskwaki (Fox) gave a decoction of burdock to women in labor as an analgesic to ease childbirth pain. The Potawatomi brewed the roots into a beverage as a “blood medicine” to fortify and cleanse the blood. Several other tribes, from the Iroquois to the Cherokee, similarly employed burdock roots or seeds for treating ailments like rheumatism, venereal disease, and skin eruptions. These applications show a remarkable convergence with Old World uses, suggesting Indigenous healers keenly observed the plant’s effects and incorporated it as a naturalized medicine once it appeared on their lands.

Burdock also entered folk cuisine of some Indigenous groups – for example, some nations reportedly cooked the young stalks or roots as food, likely after learning from European settlers. Across Africa (where Arctium species are less common), burdock isn’t prominent in traditional medicine, but in North Africa (where it grows) it has been used similarly as in Mediterranean Europe for skin and digestive issues. Latin American herbal traditions (post-Columbian) also picked up burdock, calling it e.g. lampazo in Spanish, used as a depurative herb.

Integration into Agricultural & Seasonal Cycles: Traditionally, people understood burdock’s biennial cycle and timed their usage accordingly. Farmers and foragers in Europe and Asia would harvest first-year roots in autumn or early spring (when energy is concentrated in the root). This seasonal knowledge ensured the roots were tender and rich in nutrients (older roots turn fibrous). In Japan, burdock has long been cultivated as a crop; the seeds are sown in summer, and the first-year roots are dug in late autumn before they become too fibrous. Traditional farmers incorporated burdock into rotational cycles – for example, planting it on field edges or fallow plots as a temporary crop that also helped break up soil. In some regions of Europe, burdock was a “kitchen garden weed” – tolerated or even planted in corners for use as food or medicine. Its presence was also tied to the seasonal calendar: Experiential Wisdom: Spring burdock greens and stems were eaten as one of the first bitter greens (to stimulate digestion after winter), and autumn roots were dug for hearty stews and remedies to prepare for winter. In East Asian farming, burdock’s robust growth made it a fitting summer crop; farmers would intercrop it or use it after small grains. Notably, burdock’s flowering in midsummer signaled time to cut the stalks (preventing burs from seeding everywhere) – a task often woven into the agricultural routine to keep the plant’s spread in check while still benefiting from its uses.

Mythology & Symbolism:

Myth & Folklore: Despite its wide use, burdock has relatively sparse formal mythology, yet rich folkloric symbolism. In parts of Europe, burdock was associated with protection and cleansing. Folk healers and witches hung burdock burs or leaves by doorways and windows to ward off evil or lightning. In Germanic folklore, burdock was called “Thor’s plant” (e.g. Toënnersbladen in some dialects), linking it to Thor, the thunder god. This reflects the belief that burdock could protect homes from lightning strikes – possibly because of its sturdy, grounded nature or simply a mythic association. In Victorian Language of Flowers, burdock symbolized “tenacity” or “importunity” (because of how the burrs cling obstinately) as well as “touch-me-not” (a humorous warning of its sticky burs). Indeed, children in Britain sometimes played a courting game: throwing burdock burrs at someone – if the burr stuck, it was said that person loved you back! Thus, burdock burrs became tokens in a rustic love divination ritual (albeit a prankish one).

Folklore often casts burdock as a mischievous character: English writers dubbed it “the mischievous plant” or a “robber” for how it “steals” wool from sheep and tangles in travelers’ cloaks. Yet simultaneously, the plant earned respect for its virtues; medieval European herbals by writers like Hildegard of Bingen mention burdock favorably. Hildegard (12th century Germany) even hinted at burdock’s use for treating tumors, well ahead of her time – a prophetic insight later mirrored by the use of burdock in some anticancer herbal formulas (e.g. the Hoxsey formula in the 20th century).

Symbolic Meanings: Because burdock persistently attaches itself via its burs, it came to symbolize persistence and clingy love. One old nickname “Love Leaves” for burdock alludes to its heart-shaped leaves and its tendency to stick to passersby, as if the plant “loves” you so much it won’t let go. Another curious name “Philanthropium” (from Greek “loving mankind”) was sometimes applied to burdock, perhaps tongue-in-cheek for the burs’ habit of sticking to people. In magical traditions, burdock root is used in protective magic – for example, carrying a piece of root in a sachet or pocket charm was thought to ward off negativity or even gossip. Modern pagan practitioners note that since burdock in herbal medicine cleanses toxins and negative humors, magically it’s seen as cleansing bad energy and offering protection. Burdock’s earthy, hearty energy is often described as grounding: it “anchors” one’s spirit, much as its deep root anchors it in the earth. Some folklore also links burdock to abundance – in parts of Eastern Europe, motifs of burdock appear on folk embroidery and even old flour sacks as symbols of plenty and resilience.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK):

Ecological Role & Stewardship: Indigenous and local peoples have long observed how burdock behaves in the wild. TEK observations note that burdock thrives on disturbed soils – it often appears around old homesteads, animal pens, or floodplains. First Nations elders, for instance, might note that where the land was disturbed by settlers or livestock, burdock moves in, performing an ecological healing role by covering bare soil and breaking up hard ground with its roots (much like other pioneer plants). Traditional Wisdom: Some Indigenous stewards regarded plants like burdock as “Earth’s bandages” – emerging on wounded land. While not native, burdock in North America still found a niche in disturbed ecosystems, and knowledgeable foragers would harvest it to prevent it from overwhelming an area while gleaning its benefits. Traditional gatherers often had an ethic: “harvest in a way that benefits the ecosystem.” In practice, for burdock this meant digging some roots (which thins the population and loosens soil) and cutting flowering stalks for use before seeds set, to curtail its rampant spread. Such practices align with modern invasive species management, showing TEK’s intuitive understanding of balance.

In its native Eurasian habitats, burdock was part of the natural cycle in forest clearings and along riverbanks. European peasants observed that after two years, burdock yields to later successional plants – its role is temporary soil improvement and providing food for wildlife (and people) in those first years. This understanding is reflected in old European farming lore: burdock’s big leaves were plowed under as green manure occasionally, recognizing their nutrient value. Farmers noticed that burdock leaves, when they rot, enrich the soil and that fields where burdock grew vigorously one year might have better fertility the next (a hint at its dynamic nutrient accumulation).

Ethical Relationships & Practices: Some Indigenous TEK incorporates ceremony even with introduced plants. It’s documented that Anishinaabe or Cree healers, for example, when using burdock (an introduced “weed”), would still offer tobacco or prayers to honor the plant’s spirit – treating it with the same respect as native medicinal plants. They taught that all plants, whether indigenous or newcomer, have a spirit and purpose. This respectful stance is an important aspect of TEK: rather than simply labeling burdock a weed, traditional wisdom finds a relationship with it. Ethical harvest guidelines (still relevant today) included: take only what you need, leave some roots to continue the line, and try not to scatter the burs in unwanted areas. Some communities even found uses for the burs – e.g. stuffing woven baskets with burs to catch fleas or using burs as a natural fiber for craft (taking advantage of their hooks), which doubled as a way to neutralize their spread.

Cultural Disruption & Rematriation:

Impact of Colonialism/Modernization: The story of burdock in North America is intertwined with colonial history. Burdock likely arrived with European settlers – possibly in contaminated seed or feed, or attached to livestock wool and clothing. As such, its spread coincided with the displacement of native plants and cultures. Some Native American herbal knowledge was disrupted by colonization, and burdock’s introduction is a small chapter of that upheaval. Because it was foreign, some indigenous herbalists learned of burdock’s uses through cross-cultural exchange (with settlers or later via ethnobotanical literature) rather than ancestral knowledge. In a sense, burdock’s takeover of disturbed lands can be seen as part of the ecological disruption of colonization – it often outcompeted native plants that indigenous peoples relied on. For example, burdock invading a meadow might suppress native thistles or wild roots that were traditionally harvested. Similarly, in Europe, modernization reduced reliance on wild plants like burdock; by the 20th century it was often eradicated as a nuisance in “modern” agriculture, leading to loss of folk knowledge about using it.

However, burdock also became a plant of the people in tough times. During periods of scarcity (e.g. war or famine in Europe/Asia), burdock root was a vital wild food – an accessible nourishment when crops failed. As industrial agriculture and “weed-free” monocultures spread, burdock was marginalized as an undesirable weed, symbolizing how modern practices can undervalue resilient wild plants.

Rematriation & Restoration: “Rematriation” refers to restoring the sacred relationship between plants and people, often in an Indigenous context. While burdock is not originally native to the Americas, some Indigenous-led herbal circles include it in discussions of healing the land and community. Rematriation here might mean teaching younger generations the uses of burdock rather than simply spraying it with herbicide. Across North America, herbalists and permaculturists are “rehabilitating” burdock’s reputation – from invasive weed to valuable ally. For example, community gardens now sometimes allow a controlled burdock patch for education and harvest. Some First Nations are incorporating introduced medicinal plants like burdock and dandelion into healing programs, acknowledging that these plants have become part of the landscape and can contribute to community health.

In its homeland (Europe/Asia), there’s been a resurgence of interest in burdock as well. Urban foragers and traditional food enthusiasts in Europe are reclaiming burdock recipes, and small farms are once again growing burdock root for markets (especially to meet demand in Asian cuisine and herbal medicine). This revival is a form of cultural restoration – reconnecting with the ancestral knowledge of a plant that was nearly forgotten in the rush of modernization.

Efforts for Protection: Although burdock is not endangered (quite the opposite), “protection” in this context means preserving its knowledge. Ethnobotanical organizations and elders are recording the stories and uses of burdock so that this wisdom isn’t lost. There is also a gentle movement to protect burdock’s niche in agroecosystems: rather than eradication by chemicals, some farmers opt for balanced control, using livestock or manual removal in key areas but leaving burdock in wild margins where it supports pollinators and has soil benefits. This shift reflects a more reciprocal approach: understanding that even a weed can play a role, and finding a harmonious coexistence.

In summary, burdock’s cultural journey is one of a maligned weed being re-recognized as a gift. Through rematriation of plant knowledge and regenerative land practices, people are once again listening to what burdock has to teach – about resilience, adaptability, and the potential healing in even the most humble of plants.

2. Nutritional Profile & Health Benefits

Macronutrients: Scientific Evidence: Burdock root is a low-calorie, high-fiber food. A 100 g portion of raw burdock root provides only about 72 kcal. It consists primarily of carbohydrates (~17.3 g/100g), much of which is in the form of inulin and other non-starch polysaccharides. Inulin is a soluble fiber (a fructan) that acts as a prebiotic, supporting gut flora. The fiber content (~3.3 g per 100g) contributes to laxative effects and improved digestion. Protein is low (about 1.5 g/100g) and fat is minimal (0.15 g). The root has no cholesterol and very little natural sugar. Essentially, burdock root’s macronutrient profile is akin to a starchy root vegetable but with more fiber and less digestible carbohydrate than a potato or carrot. This makes it filling yet gentle on blood sugar. Traditional Wisdom: In times of scarcity, burdock root’s carbohydrates (largely inulin) were a sustaining energy source. However, because inulin isn’t broken down into glucose rapidly, it was often noted that diabetics could consume burdock safely in moderate amounts (modern science confirms inulin’s benefit in blood sugar regulation).

Micronutrients: Scientific Evidence: Burdock root contains a spectrum of vitamins and minerals in modest amounts. It is particularly notable for its potassium content – ~308 mg per 100g (about 6–7% of daily value). Potassium supports heart and muscle function, and burdock’s high K with almost no sodium is favorable for cardiovascular health (traditional herbalists used it as a gentle blood pressure aid). The root also provides small but useful quantities of magnesium (~38 mg, ~9% DV), manganese (~0.23 mg, 10% DV), calcium (~41 mg, 4% DV), iron (~0.8 mg, 10% DV), and phosphorus (~51 mg, 7% DV). Trace elements like zinc, selenium, and copper are present in minor amounts. In terms of vitamins, burdock root has several B vitamins: notably pyridoxine (B6) (~0.24 mg, 18% DV) and some folate (~23 µg, 6% DV). It also contains vitamin E (0.38 mg) and vitamin C (~3 mg) in small quantities. While not a powerhouse of vitamins, these contribute to its overall nutritional tonic effect. Traditional/Experiential Wisdom: People considered burdock a spring “cleanser” and strengthener, likely because of this mix of minerals – it “feeds the blood.” For example, the presence of iron and B6 can indeed support blood health and energy, aligning with folk use as a “blood builder.” The potassium contributed to its folk use as a diuretic (helping kidneys flush out waste and maintaining electrolyte balance). Moreover, traditional diets valued burdock root soup or tea as a remedy for weakness or convalescence, implicitly tapping into its mineral content for replenishment.

Bioactive Compounds: Scientific Evidence: Burdock is rich in phytochemicals that have medicinal activity. Key compounds include polyphenols (especially caffeoylquinic acid derivatives like chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, and cynarin), lignans such as arctiin and its aglycone arctigenin, and flavonoids like quercetin and luteolin. The root contains an array of phenolic acids – one study detected at least 17 different phenolics in burdock root powder. These contribute to strong antioxidant capacity: indeed, burdock root extracts can scavenge free radicals and have demonstrated significant in vitro antioxidant activity. Inulin, while a fiber, also acts as a prebiotic and can influence metabolism (it’s known to help reduce blood sugar and cholesterol levels). The seeds (burdock fruit) contain lignans like arctigenin which have shown anti-inflammatory and anticancer properties in research. Burdock leaves have sesquiterpene lactones (which can be antimicrobial but also can cause contact dermatitis in some people – more on safety later). Another notable compound is plant sterols (like sitosterol) which may contribute to cholesterol-lowering effects. The root’s bitter constituents stimulate digestion (hence classed as an “alternative” or metabolic tonic in herbal terms). Overall, burdock’s bioactive profile explains many of its health effects observed by traditional practitioners.

Medicinal Uses & Clinical Evidence:

Traditional preparations (teas, salves, tinctures): Traditional Wisdom: Burdock has been lauded as one of the best “blood purifiers” in Western folk medicine. Typically, the dried root is used to make a decoction (tea) – simmering the roots to extract the bitters and inulin. Such teas were taken to treat skin problems (eczema, psoriasis, acne), arthritis, gout, and as a general detoxifier in spring. Burdock root decoction, sometimes combined with dandelion, is a classic blend for skin eruptions and liver support. The seeds (called “burdock burrs” or Niu Bang Zi in TCM) were traditionally crushed and steeped to make a tea for sore throat, colds, and measles rash (as a diaphoretic and anti-inflammatory). Poultices of fresh burdock leaves or a salve from burdock root oil have been used on skin lesions, boils, burns, and bruises – old English herbal lore describes applying burdock leaves to draw out infection and reduce swelling. In culinary medicine, eating burdock (in soups, stews, pickles) was believed to build strength, improve appetite (the bitterness stimulates digestion), and relieve chronic constipation. Native American remedies, as noted, included cough syrups from the leaves and various decoctions for pain and blood ailments.

Modern herbal insights & pharmacological actions: Scientific Evidence: Modern studies have begun validating many of these uses. Burdock root indeed has anti-inflammatory effects: extracts have been shown to inhibit inflammatory mediators, which supports its efficacy in arthritis and skin inflammation. It also exhibits antibacterial and antifungal activity – burdock leaf extract can inhibit oral microbes and possibly skin pathogens. One clinical study found that burdock root tea improved the inflammatory status and oxidative stress in patients with knee osteoarthritis, lending evidence to its traditional use for rheumatism. Burdock’s inulin content and polyphenols contribute to its observed antidiabetic effect: animal studies show burdock root extract can lower blood glucose and improve lipid profiles. For example, in one rat study, burdock extract given to high-fat-diet rats reduced their weight gain and blood cholesterol levels significantly. Another study in ulcer-induced rats found burdock’s anti-inflammatory properties promoted faster gastric ulcer healing.

Perhaps most exciting is burdock’s potential in cancer adjunct therapy. The lignan arctigenin from burdock seeds has demonstrated the ability to inhibit tumor cell growth, including showing potent activity against pancreatic carcinoma cells in experiments. Arctigenin and related compounds may induce cancer cell apoptosis and inhibit metastasis (ongoing research is exploring this for cancers like pancreatic, breast, and liver). In fact, burdock is one of the four herbs in the famous Essiac formula (a North American herbal cancer remedy), chosen for its anti-tumor and detoxifying reputation. While large clinical trials are lacking, these phytochemicals justify further research into burdock as a nutraceutical. Additionally, burdock has shown hepatoprotective effects in lab studies – it can protect liver cells from toxic damage (e.g. one study found burdock extract helped prevent acetaminophen-induced liver injury in mice, likely through its antioxidant action).

In dermatology, burdock’s historical use for skin diseases is supported by its anti-inflammatory and possibly hormone-balancing effects (useful in acne). A small human study found a burdock root extract could improve signs of photo-aging in skin, possibly due to enhancing dermal matrix components. Overall, the clinical evidence (though still emerging) aligns well with the broad traditional uses: burdock is an alterative (metabolic tonic) that gently aids various systems – digestive, urinary, integumentary – in cleansing and restoration.

Safety & Contraindications:

Allergies: Scientific Evidence: Burdock is generally safe for most people when consumed as food or mild tea. However, it belongs to the daisy family (Asteraceae), and individuals allergic to ragweed, daisies, or chrysanthemums could have allergic reactions. Handling burdock leaves or burrs can cause contact dermatitis in sensitive individuals. The large leaves have fine hairs and some lactones that may irritate skin – wearing gloves during harvest is recommended if you have sensitive skin. If burdock burrs or “pappus” hairs contact eyes or mucous membranes, they can cause significant irritation (even infection) – an important caution for foragers and farmers.

Drug Interactions: Burdock’s root has diuretic effects and can modestly lower blood sugar. Therefore, those on diuretics or diabetes medications should use caution, as burdock might potentiate these effects (leading to more urination or hypoglycemia). Also, burdock’s blood-thinning potential hasn’t been well-studied, but as a precaution, some herbalists advise discontinuing high-dose burdock before surgery. Burdock can bind to heavy metals (it’s used in some chelation formulas), so theoretically it could affect absorption of minerals or medications if taken simultaneously – spacing doses is prudent.

Pregnancy and Children: Traditional Wisdom: Old herbals often cautioned that strong alteratives like burdock should be used in moderation during pregnancy. While there’s no documented harm in normal food use, out of an abundance of caution many sources advise pregnant women to avoid medicinal doses of burdock due to its uterine stimulant potential (not conclusively proven, but emmenagogue effects are possible given its influence on hormones and blood flow). Similarly, children under 2 years old are often advised not to ingest burdock remedies, as their systems are more delicate and the effects on them haven’t been studied. Topical use of burdock leaf poultices on pregnant women’s lower abdomen is also discouraged (though historically it was sometimes used to ease delivery by Meskwaki women late in labor, this is not recommended without professional guidance).

Toxicity: Importantly, burdock is not poisonous – all parts are edible in some form. There is a caveat: burdock is sometimes confused with deadly nightshade (Atropa belladonna) or belladonna lily by untrained foragers, since young burdock leaves can resemble certain large leaves. Misidentification has led to poisoning in rare cases. Thus, correct ID is crucial. Only harvest burdock if you are sure of the plant’s identity (the woolly leaf underside and burs are key giveaways). Another safety point: burdock’s burs have caused trauma if ingested by animals – e.g. livestock or dogs nibbling seedheads can get the spines stuck in their mouth or throat. For humans, this isn’t usually an issue, as we don’t eat the burs, but one should remove any burs before drying plant material for tea (they’re not typically used internally in Western preparations; TCM uses the cleaned seeds inside the burs).

Side Effects: Burdock’s diuretic effect means it can cause increased urination – so staying hydrated is advised. Occasionally, people report mild digestive upset (loose stools or gas) when consuming a lot of burdock, likely due to the inulin fermenting (a common effect of high-fiber inulin-rich foods, similar to Jerusalem artichoke). Starting with small doses allows the gut to adjust. In very high amounts, burdock could deplete electrolytes (from urination) or lower blood sugar too much – so moderate intake is key. Summary: used as a food or in moderate therapeutic doses, burdock is quite safe. One must simply be mindful of allergies, medication interactions, and not consuming contaminated plants. It’s wise to source burdock from clean soil (avoid roadsides or polluted areas) because the plant may uptake heavy metals from contaminated ground – this is a general wildcrafting rule for any deep-rooted herb.

In closing, burdock stands as a nourishing herb-food with a remarkable safety profile and a breadth of benefits, bridging nutrition and medicine. It carries a legacy as a gentle yet potent healer, confirmed by both traditional experience and modern science.

3. Soil & Ecosystem Roles (Ecological, Agricultural, Regenerative)

Burdock is not only valuable to humans; it also plays distinct roles in soil health and ecosystems. As a pioneering weed, it often colonizes disturbed ground, and in doing so, it can influence soil structure, nutrient cycles, and biodiversity.

Soil Building & Nutrient Management

Influence on Soil Structure and Fertility: Scientific/Regenerative Insight: Burdock’s deep taproot acts like a natural “subsoiler” or biological plow. It can penetrate hard, compacted soils, creating channels that later become pathways for water and root penetration of other plants. When the taproot dies or is harvested, it leaves behind an organic tunnel that improves aeration and drainage. This can help alleviate soil compaction in degraded areas. Regenerative farmers often notice that where burdock (and similar taprooted pioneers) grow, the subsoil is brought closer to the surface. Burdock roots draw up minerals from deeper layers – calcium, iron, magnesium – accumulating them in the plant tissue. When the plant dies back, those minerals return to the topsoil via decomposed roots and leaves, thereby enriching the topsoil (a concept known as “dynamic accumulation”). Experiential Wisdom: Homesteaders have observed that burdock tends to grow in high-nitrogen soils (often near livestock areas or compost heaps), and its presence can indicate fertile soil. Paradoxically, it further fertilizes the soil by mining nutrients and adding biomass. Early permaculturists list burdock as a potential dynamic accumulator of Iron (Fe) and perhaps other micronutrients. While formal science on dynamic accumulators is ongoing, anecdotal farm observations support that chopping and dropping burdock leaves returns those mined nutrients to upper soil layers in plant-available forms.

Composting Benefits and Nutrient Cycling: Practical Application: Burdock’s large leaves (which can reach over a foot long) and fleshy stems provide excellent green matter for composting. They break down fairly readily (especially if chopped) and contribute a good carbon/nitrogen mix – green burdock material is nitrogen-rich and moist, helping to heat up compost piles. Traditional farmers in some areas would intentionally collect burdock leaves during summer weeding and layer them into manure piles to boost compost microbial activity (the mucilage and sugars in the plant can feed compost microbes). Burdock’s tendency to grow in nutrient-rich spots means it often absorbs excess nitrates; by composting those plants, the nitrates are redistributed in a more stable form. There is also an allelopathic advantage: unlike some weeds, burdock doesn’t release persistent toxins that could harm compost; to the contrary, its decomposition is benign. Regenerative tip: You can make a potent compost tea or liquid fertilizer by steeping burdock leaves in water – gardeners use this “weed tea” to capture soluble nutrients (especially potassium and calcium from the leaves) and apply it to crops. In Korean Natural Farming, farmers create Fermented Plant Juice (FPJ) from wild weeds like burdock, precisely to harness their nutrient content and growth hormones. For example, mixing chopped burdock leaves with brown sugar and fermenting yields a liquid rich in enzymes and minerals that can be diluted and sprayed as a foliar feed or soil drench (a practice widely used by KNF practitioners to boost soil fertility in a natural way). Thus, burdock contributes to nutrient cycling by taking up nutrients that might otherwise leach away, then readily giving them back through human-facilitated composting or natural decay.

Microbial Life (Fungal/Bacterial Relationships): Scientific Perspective: Burdock, like most Asteraceae, forms associations with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) in the soil. These symbiotic fungi colonize burdock’s roots, extending far into the soil and aiding in phosphorus uptake, in exchange for plant sugars. By hosting mycorrhizae, burdock can actually improve the local soil microbiome – AM fungi networks can connect to other nearby plant roots as well, potentially aiding neighbouring plants. In ecosystems, burdock’s mycorrhizal associations help initiate soil life in disturbed areas. Additionally, the carbohydrates exuded from burdock roots (including simple sugars and perhaps inulin fragments) feed soil bacteria. Observationally, one finds rich microbial activity around burdock roots – the rhizosphere has increased microbial biomass, which contributes to soil aggregation and nutrient transformations. Emerging Hypothesis: There is speculation in regenerative circles that burdock’s inulin might fuel beneficial fungi and actinomycetes that help break down organic matter. Although specific research on burdock’s microbiome influence is limited, we know that wherever a large taproot decays, it creates a hotspot for soil organisms (earthworms often follow decaying root channels). Indeed, after a burdock root rots, one often finds earthworm castings in the cavity – evidence that soil fauna are utilizing the organic matter. This points to burdock serving as a “compost in place”: it grows, accumulates biomass and nutrients, and if left or slashed, it decomposes in situ, feeding a whole web of microorganisms.

Mycorrhizal Relationships and Partnerships: Scientific Evidence: As noted, Arctium minus likely participates in the common mycorrhizal network (CMN) of an ecosystem. This means burdock could be sharing nutrients with other mycorrhizal plants through fungal hyphae. In pasture settings, for example, burdock might indirectly benefit nearby grasses or clover by improving soil tilth and hosting fungi that also connect to those forage roots. Some regenerative farmers observe that after a few years of allowing burdock (and then removing it), the subsequent crops in that spot perform better – possibly due to the legacy of improved fungal networks and organic matter. Burdock does not have special nitrogen-fixing partners (like legumes do), but it can work in tandem with such plants: for instance, one might find burdock growing amidst clover or vetch; the clover fixes nitrogen, the burdock mines minerals – together they enrich the soil. In certain studies of invasive Asteraceae, robust mycorrhizal symbiosis has been linked to their success in new territories. Burdock’s vigorous growth in North America could partly be due to hooking up with ubiquitous AM fungi to exploit soil resources efficiently.

In summary, burdock acts as a pioneer soil engineer, improving structure and recycling nutrients. While farmers often curse it as a weed, a regenerative lens sees burdock as an ally in restoration – a plant that appears to heal damaged soils by aerating, mulching (with its own leaves), and feeding the unseen soil life.

Biodiversity & Wildlife Support

Supported Species (Insects, Animals, Fungi): Although burdock isn’t a classic pollinator plant like wildflowers, it does provide for a variety of creatures. Its purple florets produce nectar and pollen that attract bees and other insects. Scientific Observation: Burdock is noted to be visited by bumblebees, honeybees, miner bees, and leaf-cutting bees which collect its pollen and nectar. These pollinators help fertilize the burdock, and in turn get a late summer food source (burdock flowers mid to late season, when some other sources may wane). Butterflies and moths also visit; notably, the Painted Lady butterfly (Vanessa cardui) uses burdock as a host plant – its caterpillars will feed on burdock foliage. (The Painted Lady is famous for using thistles and related plants; burdock, being thistle-like, is on the menu for its larvae). Other lepidoptera such as the Ghost Moth or certain Hawk moths may also nibble burdock leaves.

For larger wildlife, burdock’s role is mixed. Deer or moose have been known to browse young burdock leaves occasionally (the young leaves are not too spiny and provide some moisture and protein). Livestock like cattle or horses will graze burdock leaves if nothing better is available (the leaves are not toxic, just bitter). In fact, some farmers note their sheep and goats will eat burdock leaves readily – goats sometimes strip burdock plants of leaves (avoiding the spiny burrs). This can actually be a useful biological control and simultaneously a nutritional supplement for the animals (burdock leaves contain minerals and chlorophyll that can benefit livestock health, though in large quantities they might taint milk as noted later).

Birds: The relationship with birds is a double-edged sword. On one hand, burdock thickets provide shelter for small birds and the dried burs in winter might trap snow and create insulated microhabitats for overwintering insects (which birds could eat). There are anecdotal reports that some birds like goldfinches or sparrows will peck at burdock seed heads to eat the seeds. However, the burs also pose a hazard: tiny birds or bats can get entangled in the super-sticky burr clusters. It’s recorded that small birds (like kinglets or warblers) have died by being snared in burdock burrs when they brush against them. This unfortunate aspect is something conservationists in some areas manage by removing burdock from critical bird habitats. Larger mammals – bears, wolves, etc. – aren’t particularly interacting with burdock except perhaps getting burrs caught in fur (which, while annoying to them, does assist seed dispersal).

Fungi: As a decaying plant, burdock likely supports decomposer fungi. Its big fleshy taproot is a feast for soil fungi once it dies. One might find mushrooms (from genera like Pythium or Fusarium – not beneficial, but part of decomposition) colonizing a dead root. But also, beneficial Trichoderma or other soil fungi may feed on it. Burdock doesn’t have a known specialized fungus (no rust or mildew that’s unique – though it can get powdery mildew on leaves). In sum, burdock supports a micro-ecosystem: insects in its flowers, herbivores on its leaves, and microbes in its root zone.

Role as Keystone or Indicator Species: Burdock is not typically considered a keystone species in ecosystems (it’s often an introduced opportunist). However, in certain disturbed ecosystems, it functions as a temporary keystone by being one of the first robust life forms to occupy barren ground, thus enabling succession. For instance, on an abandoned farm lot, burdock might dominate initially, providing ground cover and biomass, and then give way to shrubs and trees – in that initial phase, it can be critical for preventing erosion and providing habitat (even if minimal) where none was before. As an indicator, burdock often signals rich soil with high nitrogen. If burdock proliferates in a pasture, it might indicate over-manuring or nutrient buildup (common around livestock yards). It also indicates disturbance – seeing lots of burdock in a natural area suggests the soil was disrupted (by flooding, human activity, or overgrazing). In that sense, land stewards might read burdock’s presence as a sign to adjust management (for example, if burdock invades a pasture, it may mean the grasses were weakened by overgrazing, opening the door for burdock).

While burdock doesn’t specifically “support” a large number of species the way a true keystone like oak or pine might, it does play a modest yet meaningful part in biodiversity. Pollinators benefit, some herbivores benefit, and even its pesky burs can disperse seeds of itself and accidentally other materials (burs can carry little bits of organic matter or hitchhiking seeds of other plants, inadvertently aiding their spread too).

In regenerative farming, one could intentionally allow a few burdock to flower on the margins to increase pollinator forage diversity. The purple blooms are quite attractive to insects, and having different bloom times (burdock often blooms later in summer) helps sustain pollinators through the season. Permaculturists sometimes mention burdock in “insectary strips” – though you wouldn’t want it to seed everywhere, managed flowering can be part of a pollinator strategy.

Overall, in an ecosystem context, burdock is a transient but beneficial player: a nurse plant for soil recovery and a resource for certain insects and animals, albeit with some management challenges due to its burrs.

Succession & Ecosystem Stabilization

Role in Ecological Succession: Scientific/Observational: Burdock typically appears in the early to mid stages of succession. It thrives on disturbed ground – think of landslides, clear-cuts, overgrazed pastures, or abandoned lots. In the first year or two after disturbance, annual weeds and pioneer perennials colonize; burdock, being biennial, often establishes in the first year (rosette stage) and then dominates in the second year when it flowers. Its broad leaves can shade out smaller annuals, thus preparing the site for more perennial cover. However, burdock itself is not a long-term competitor in closed communities – as shrubs and trees grow, burdock populations diminish due to shading and litter accumulation. This means burdock’s natural role is to stabilize and enrich soil in the interim between bare ground and more permanent plant cover. Its large canopy leaves protect the soil from erosion by intercepting raindrops and shading the ground. Its root, as described, breaks up hardpan and improves infiltration. In doing so, burdock facilitates conditions for other plants. After a couple of cycles of burdock, the soil often has more organic matter (from decayed burdock) and channels for woody plants to take root. You might observe, for example, on an abandoned field: year 1 ragweed and lamb’s quarters, year 2 burdock and thistles, year 3 young saplings starting to pop through the dying burdocks – by year 5, burdock is much reduced as brambles or young trees overtop it. So burdock is a “covering nurse” that helps the successional trajectory. Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Indigenous observers would see that after a wildfire or clearing, broadleaf pioneers like burdock (where present) help Mother Earth heal by quickly covering open soil. It’s doing the work of ecosystem stabilization in those early years.

Impact on Water Cycles and Erosion: Burdock, with its taproot, can significantly improve water infiltration. The root channels water deeper into the subsoil, reducing surface runoff. In areas where burdock grows densely on slopes (say, roadside embankments), it can help hold the soil together with its root network and reduce erosion. The large leaves also slow down water flow and act almost like mulch when they die back. Emerging Observation: Some permaculture practitioners note that burdock’s presence increases moisture retention in soil – partly because the shade from its canopy reduces evaporation, and partly because its decaying matter increases the soil’s sponge-like qualities. In a small way, burdock contributes to recharging groundwater by funneling rain into its root holes. On the flip side, burdock in riparian zones (stream sides) might trap sediment around its bases, building soil. However, if burdock dies off en masse, there could be a lot of dead matter that, if not succeeded by others, could temporarily expose soil. But nature usually has overlapping cycles to avoid that gap.

It’s interesting that in drought conditions, burdock often wilts less than shallow annuals – its deep root taps moisture reserves. This makes it somewhat drought-resistant and means it can keep living root in soil during dry spells, which helps maintain soil structure and microbial life when other plants have withered. Once rains return, burdock rapidly sends up new growth, aiding the recovery of vegetation cover.

In conclusion, burdock’s successional role is as a pioneer and soil conditioner. It helps stabilize a site until longer-lived perennials take over. By improving soil fertility and structure, it essentially works itself out of a job – making the site attractive for other plants that eventually shade it out. From a regenerative agriculture standpoint, understanding this role lets us mimic or utilize burdock intentionally. For example, after decompacting a patch with burdock for 2 years, one might then plant a fruit tree or perennial crop in that improved spot (perhaps after removing the burdock or letting it naturally cede). This mimics natural succession but directed toward a productive species.

Companion Planting & Pest Management

Companion Benefits and Polyculture Roles: Burdock is not a common intentional companion plant in gardens (due to its size and weedy nature), but in a wild or permaculture setting, it can have some complementary interactions. For shallow-rooted plants (like lettuce, most herbs, or even young trees), burdock can act as a “dynamic accumulator companion”. For example, one might allow some burdock at the edge of a garden bed; its roots pull up nutrients which nearby plants can access through the shared mycorrhizal network or when leaves drop and decompose. Burdock’s big leaves can provide partial shade to shade-tolerant companions in hot weather. One could imagine interplanting a few burdock on the west side of heat-sensitive crops to give afternoon shade. Historically, some gardeners planted burdock with vining plants like squash – the squash could climb over the burdock or use it as living trellis support (the burs might make that complicated, though!). In Japan, burdock is grown in rows much like carrots; it doesn’t co-plant with other crops in the same row due to its size, but farmers sometimes plant quick crops (radishes, greens) between widely spaced burdock rows early on, since burdock’s initial rosette leaves have some space between before they fill in.

In orchard guilds, burdock can be a beneficial understory in the early establishment years. For instance, around a young fruit tree, a burdock plant or two at the drip line could mine nutrients and share them. Its broad leaves suppress competing grasses (acting as living mulch) and can be chopped and dropped to continually mulch around the tree. Some permaculturists include burdock in tree guilds with the warning to prevent seeding. Because burdock is biennial, one strategy is to let first-year rosettes grow near an orchard tree and then cut them before they flower the second year, leaving the root to decompose in place – effectively serving as a short-term nutrient pump and then yielding space to the tree as it grows. Burdock’s compatibility tends to be better with perennial systems than annual veggie rows, given its robust nature.

As a companion in pasture, interestingly, moderate burdock presence can benefit other forage: the partial shade might keep some grass greener in summer and the root channels can improve pasture soil for deeper-rooting forages. But too much burdock is obviously a pasture problem as animals avoid dense stands.

One potentially positive pairing is burdock with nitrogen-fixing cover crops. If one sows clover or vetch in a disturbed area and allows existing burdock to remain, the clover fixes nitrogen which burdock uses to grow huge, and burdock brings up minerals that the clover can benefit from – a complementary nutrient partnership. This combination can rapidly improve soil (though one might then remove burdock after a cycle to let the clover or desired plants fully take over).

In summary, while burdock is usually seen as a competitor, in a designed polyculture it can play the role of miner, mulcher, and protector for a limited time. The key is managing its aggressive traits (size and seeding) so that it assists rather than overwhelms its companions.

Natural Pest and Disease Deterrent Uses: Burdock is not known for strongly repelling many pests (unlike, say, marigolds repel nematodes, or alliums repel some insects). It has no noted companion effect like “keeps bugs off neighbors.” However, there are a few interesting notes:

Trap crop potential: Burdock’s large, coarse leaves may attract certain pests as an alternative host. For example, some gardeners report that aphids sometimes cluster on burdock leaves (especially if the plant is lush with nitrogen), which could draw them away from more delicate crops. Similarly, cabbage worms or leaf beetles might chew burdock instead of vegetable greens if given the choice. If used intentionally, one could plant a burdock on garden margins to lure pests and then dispose of that plant, thus protecting main crops. This is speculative but fits trap-crop logic.

Physical pest control: The sticky burs have been thought to catch crawling insects. Folklore suggests scattering dried burdock burs around root crops to deter rodents or insect larvae, as they might get spines in their noses or find movement difficult (though evidence is slim, it’s a creative idea).

Disease considerations: Burdock can host powdery mildew, and possibly root rot fungi, but these are generally not the same species that attack fruit or veggies (except powdery mildew is ubiquitous). So it’s not a major disease spreader. In fact, by improving air flow and drying out upper soil, its presence might indirectly reduce some fungal diseases in a field. Conversely, dense burdock foliage could harbor moisture-loving slugs or snails underneath – so in that sense it might increase slug pressure near delicate plants.

One pest-deterrent use that is documented historically: burdock leaf poultice or ointment was applied on livestock to keep flies away from wounds (the smell and bitterness might deter flies from laying maggots on sores). Farmers would bind burdock leaves on horses as a natural fly repellent and cooling pack. This doesn’t directly affect plant pest management but is a clever farm use.

Weed suppression: On the flip side, burdock’s sheer size can suppress other weeds. If you have a patch where you don’t mind burdock, it can outcompete more problematic weeds like poison ivy or certain thistles. It’s easier to pull out (in early stages) than some perennials, so letting burdock take over then removing burdock might be easier than dealing with a mix of tough weeds. Essentially using burdock as a biological fallow cover crop – it covers ground and then you remove it to plant something else in cleaner soil.

In conclusion, burdock is not a classic companion plant, but it can be integrated thoughtfully for its soil benefits and minor pest interactions. It’s a plant that demands respect in cultivation – if you treat it as a short-term team member and remove or cut it before it misbehaves (goes to seed), it can provide services in a polyculture. Many regenerative farmers might still opt for less aggressive dynamic accumulators (like comfrey) as companions, but burdock has the advantage of being native to many soils (in the sense of thriving without fuss) and is easily propagated by seed. As long as its pest (weed) potential is managed, burdock can indeed be part of a productive plant guild, offering its deep-reaching, nutrient-pumping, soil-tending talents to the benefit of other plants and the system as a whole.

4. Bioenergetic Field (Quantum Biology & Vibrational Roles)

Beyond its physical and ecological presence, burdock is often ascribed certain energetic or vibrational qualities in holistic traditions. While these aspects are more speculative and experiential, they add a layer to understanding burdock as a living being in relationship with its environment.

Energetic Signature (Flower Essences, Biodynamic Uses)

Flower Essence (Experiential/Vibrational Wisdom): In the realm of flower essence therapy – a vibrational healing modality – Burdock Flower Essence is valued for its grounding and cleansing energy. Practitioners say it addresses emotional patterns, especially deep-seated anger and negativity that have “stuck” in one’s energy field. The logic is analogical: just as burdock’s burrs stick tenaciously, so can old anger stick to a person. Burdock essence is believed to help “unstick” these emotional burrs. For example, Tree Frog Farm’s flower essence description notes that Burdock essence helps release anger tied to past wounds or authority figures, and assists in letting go of toxic attachments (even metaphoric “toxic heavy metals” in one’s energy). It’s considered protective and nurturing – “supporting us through dark times”, helping one find light in the darkness, as one essence maker poetically put it. Many see its energetic signature as aligning with the root chakra (Muladhara), given its strong root, offering stability, security, and a sense of being anchored to Earth.

In emotional healing rituals, burdock root is sometimes carried or worn to ward off negativity and to help one set healthy boundaries (since the plant clearly defines its space and doesn’t easily let go once attached!). Some also correlate burdock with the planet Jupiter in herbal astrology – Jupiter being expansive and nourishing. Indeed, one herbalist called burdock “Jupiter’s plant” for its growth and abundance, claiming it brings a stabilizing, nourishing force to the body and spirit.

Biodynamic Uses: In traditional biodynamic agriculture (Steiner’s system), burdock is not one of the primary compost preparations; however, biodynamic farmers recognize burdock’s value. Some might include burdock leaves in compost piles to introduce its energy, or make fermentations akin to biodynamic “teas.” There’s a concept of “peppering” weeds in biodynamics (burning their seeds and spreading the ash to deter them energetically); burdock as a weed could be managed this way, but also one could harness its energy by using its ashes for soil if wanting to impart burdock’s grounding quality to a field. Additionally, certain biodynamic practitioners use burdock root in homeopathic form for supporting soil microbial life or plant immunity (anecdotal practices). Burdock is sometimes mentioned as having an affinity for the planetary force of Saturn as well, due to its earthy, contracting qualities. While these correspondences vary by practitioner, the key is that burdock is seen as energetically purifying and anchoring.

Overall, its energetic signature in various modalities is one of cleansing negativity, restoring balance, and providing grounded strength. People and environments that feel “toxic” or imbalanced are thought to benefit from the subtle introduction of burdock’s energy – be it through planting the actual plant to soak up geopathic stress or using its essence in vibrational healing.

Quantum Biological Hypotheses (Light Interaction, Electromagnetic Fields)

Light & Bio-photonic Interaction: Every green plant interacts with light on a quantum level through photosynthesis. While burdock may not have any special claim here, one could ponder its large leaves and rapid growth: they capture copious sunlight and convert it into biomass efficiently. Emerging Hypothesis: Some esoteric plant researchers suggest that burdock, with its broad leaves, might have a strong bio-photonic field, meaning it could emit a notable amount of ultraweak light (bio-photons) as a result of its metabolic processes. Bio-photons are a field of study in quantum biology examining how cells may communicate via tiny light emissions. If burdock indeed has high antioxidant activity, it might also mean it manages oxidative stress well, which correlates with lower random photon emission and more coherent light output. This is speculative, but intriguing: burdock could thus be a plant that contributes a coherent light frequency to its environment, perhaps influencing neighboring organisms.

Electromagnetic Fields: All living organisms generate subtle electromagnetic fields (EMFs). A plant like burdock, with a deep root in the ground and a wide leaf span above, could act like a biological antenna, connecting earth and sky energies. One might hypothesize that burdock’s taproot conducts electrical impulses (from soil microbes, perhaps) upward, and its leaves, acting as plates, release some energy into the air. There is research showing plants emit ELF (extremely low frequency) signals during growth or distress. It’s not far-fetched that burdock’s growth—rapid and forceful—could produce measurable electrical potentials in soil (e.g., as its roots uptake ions). Traditional lore: In dowsing and earth-energy mapping, some say that big taproot weeds often sit on energetic ley lines or underground water veins, possibly attracted to those subtle currents. Burdock might then indicate spots of geomagnetic anomaly or serve to balance them.

To be clear, mainstream science hasn’t documented special EM properties for burdock in particular. But vibrational healers might say that if you sit quietly by a burdock patch, you can feel a kind of subtle hum of the earth’s energy being drawn in and radiated out. It’s described as a grounding vibrational field—likely because burdock anchors physically and thus maybe energetically anchors chaotic frequencies around it.

Microbial, Mycorrhizae & Energetic Signaling

Microbial Communication: There’s growing acknowledgment that plants and microbes communicate chemically and perhaps electrically. Burdock’s root exudates (sugars, amino acids, etc.) certainly send chemical signals that attract beneficial microbes. Emerging Theory: Could burdock also be involved in a kind of electro-chemical signaling network in the soil? Mycorrhizal fungi are known to transmit signals between plants, akin to a “wood-wide web.” If burdock is connected to this network, it may help relay distress signals or nutrient availability signals among plants. For example, if one part of the community is attacked by pests, some studies show connected plants can ramp up defenses—burdock might partake in such information exchange when present.

Additionally, burdock’s known ability to uptake heavy metals hints that it might change soil redox conditions (as it absorbs positively charged metal ions). This redox change can produce tiny electric gradients. Soil bacteria respond to electric fields; thus, burdock could indirectly shape microbial behavior through micro-electrical shifts around its rhizosphere. It’s subtle and not well-studied, but plausible.

From a vibrational insight perspective, some farmers talk about certain weeds “calling in” specific microbes needed to heal the soil. Burdock might call in, say, Actinobacteria to break down tough organic matter, or particular mycorrhizae that release phosphatase enzymes. This is essentially a co-evolutionary communication: the plant provides food for microbes that in turn provide what the plant (or the soil) needs. On an energetic level, one could say burdock orchestrates a little community around its root via vibrational resonance—perhaps its root hairs vibrate at frequencies that stimulate microbial enzymes (this is speculative but interesting to imagine in quantum biology terms).

Mycorrhizal Network & Subtle Signals: Within a mycorrhizal network, there may be not just chemical signals but also electrical impulses (recent research suggests fungi can transmit impulses reminiscent of nerve signals). A burdock integrated into such a fungal network could be seen as a node that transmits signals—for instance, if the burdock experiences drought stress, an impulse might travel through fungi to other plants, “warning” them to conserve water. If such processes hold true (still under research for many plants), then burdock, by virtue of its strong fungal ties, is a participant in the quantum-connected ecosystem where information (in the form of electrical/chemical oscillations) flows through the community. It’s almost an underground “internet” with burdock as both client and server.

To ground this in reality: Think of how burdock quickly senses and responds to the environment—fast growth when nutrients abound, or quick wilting when it’s very dry. These responses aren’t isolated; neighboring plants can detect changes in burdock’s chemical output. On a quantum level, even the rapid movement of ions in burdock’s tissues during these responses generates tiny magnetic fields, which theoretically could be detected by sensitive organisms nearby. It’s a fascinating frontier to consider that our “weeds” might be both communicators and translators of environmental conditions, maintaining ecosystem coherence.

Hypothetical Field Effects (Subtle Energy Fields & Regeneration)

Subtle Energy Fields: Many holistic land stewards believe plants emanate a vital field (often called an aura or morphogenic field) that can influence the environment. Burdock’s field, by most accounts, is robust, earthy, and resilient. Some intuitives describe stepping into a patch of burdock as stepping into a kind of fortifying energy. It feels like a safe, grounded space. This could be why historically people associated it with protection. If one subscribes to Rupert Sheldrake’s morphic field theory, one might say burdock has a strong morphic resonance of “resilience and purification,” and when you bring burdock into a degraded landscape, it may help imprint that pattern of resilience onto the land’s field, aiding overall regenerative processes in ways beyond physical soil amendment.

Regeneration Influence: In the subtle realms, burdock is sometimes said to help “detoxify” an area energetically, not just physically. For example, if land has seen trauma (pollution, war, neglect), planting burdock or allowing it to grow could assist in clearing negative energies. This mirrors its physical clearing of toxins from soil or body. Healers might even perform rituals with burdock on land: such as sprinkling burdock seed or making a burdock root brew to pour on the ground with prayers, as a way to cleanse curses or stagnant energies. These are vibrational or spiritual practices, of course, but they underline the perceived special role of burdock as a cleanser and restorer at all levels.

Some biodynamic farmers anecdotally report that land with burdock feels “calmer” or that animals grazing near burdock patches are oddly less stressed (could be because they nibble on it and get medicinal benefits, or perhaps an energetic soothing effect). While hard science can’t measure “stress fields,” in animal husbandry, if something consistently calms livestock, it’s notable.

Hypothesis: Burdock might contribute to a coherent energy field in a polyculture that supports regeneration. Imagine a field with a diversity of plants including burdock: each plant contributes its vibrational note. Burdock’s note could be a deep bass line, stabilizing the melody. Without it, maybe the field feels more chaotic. With it, there’s a certain order introduced. This is analogous to how in ecology, diversity including some strong structural species yields a more resilient system. Perhaps in the energetic dimension, including a plant like burdock yields a more cohesive life-force field that fosters regeneration of life.

It’s all quite hypothetical, but it demonstrates the holistic way we can view a plant: not just as a sum of chemical processes but as an integrated part of the landscape’s visible and invisible dynamics. Burdock, once only considered a stubborn weed, emerges in this view as a kind of energy worker plant, rooting out what is unhealthy and anchoring new vitality.

(Emerging Vibrational Theories): While concrete evidence for these subtle roles is limited, they align beautifully with burdock’s overt characteristics. Its ability to remove toxins, both in soil and herbal medicine, parallels the lore that it removes “toxic influences” energetically. Its firm anchoring root and persistent burrs parallel the idea of helping one hold ground and release stuck patterns. Thus, even if one approaches these ideas with skepticism, the metaphorical truth is strong: burdock teaches resilience and release. Whether via quantum fields or simple presence, those who work closely with burdock often report feeling more grounded and “clear” – perhaps that is burdock’s subtle gift, inviting both land and people to regenerate by clearing out what doesn’t serve and strengthening what does.

5. Animal Nutrition & Veterinary Applications

Burdock isn’t just for humans and soil – it also has applications in animal health, both as feed and as herbal medicine for livestock and pets.

Livestock Forage: Experiential Wisdom: While farmers often consider burdock a pest in pastures, many animals will eat burdock leaves opportunistically. Goats and sheep, known for their weed-chomping abilities, often nibble on young burdock foliage. Goats in particular seem to strip burdock plants of leaves (they’ll even eat tender stems) and generally avoid the burrs and tough parts. The leaves, especially when young, contain protein and minerals comparable to other forage – though they are quite bitter and fibrous when mature. Some shepherds note that sheep “love burdock leaves” and will readily eat them in late summer when grass is low. This provides a natural control of the weed and a mineral-rich browse for the flock. Cattle and horses will graze first-year burdock rosettes to some extent. In fact, an old dairyman’s tale says a bit of burdock in the pasture can be beneficial as a spring tonic for cows, owing to its high mineral content and diuretic effect (keeping their kidneys healthy after winter). However, too much burdock in a cow’s diet can flavor the milk with a bitter, wild taste. This is documented: if dairy cows ingest burdock in quantity, it may taint milk and dairy products – likely due to the volatile compounds and bitter principles transferring. Therefore, farmers usually control burdock to prevent that.

From a nutritional perspective, burdock leaves could be likened to a “free-choice mineral supplement” for livestock, given their concentrations of potassium, calcium, etc. Animals often have instinct to chew certain plants when they need those minerals. There are anecdotal accounts of horses, for instance, deliberately seeking out burdock leaves when they have skin issues or are shedding coat – perhaps an intuitive use since burdock supports skin health and metabolism.

Herbal Supplement for Animals: Traditional Veterinary Uses: In folk veterinary medicine, burdock has been used for various animals:

Horses: Burdock root is a popular component in herbal blends for horses, especially for skin conditions (like eczema or dull coat) and for “blood cleansing.” Herbalists call it an alterative for horses – improving overall metabolism and helping with arthritis or laminitis inflammation. It’s often fed dried, about 15–30 grams daily for an adult horse. This is said to support liver function and digestion in horses. Many equine supplement companies sell burdock root powder as part of detox or skin formulas. One equine herbal reference states: “burdock root is an excellent blood purifier and healing herb for skin conditions” in horses. Horse owners use it for cases of rain rot, scratches (mud fever), or chronic skin allergies – both by feeding and applying washes of burdock tea to the skin.

Caution: Horse safety – Burdock burs are a physical hazard to horses. If burs get tangled in manes or forelocks, they can rub into the horse’s eyes causing ulcers. Also if horses inadvertently eat the burrs in hay, they can develop mouth lesions and excessive salivation. Thus, while the herb is healing, the plant’s seeding structures are problematic. Horse pastures are usually kept burdock-free for this reason, but harvested root or leaves (sans burs) are fine.

Cows and other ruminants: Historically, farmers didn’t usually bother treating cows with herbs like burdock (they might simply remove toxic plants and let the cow’s diet be medicine). However, there are instances in ethnoveterinary records of using a strong burdock leaf poultice on cow mastitis (inflamed udder) to draw out heat and infection. Burdock’s anti-inflammatory and antibacterial qualities could ease mastitis – fresh leaves would be warmed and bandaged onto the udder. For internal use, a tea of burdock root might be given to a cow after calving to help cleanse the uterus and blood – akin to how it’s given as a postpartum tonic for humans. Goats and sheep could similarly benefit: one might mix a bit of burdock root decoction into their water as a spring tonic or to help with skin parasites (burdock’s sulfurous compounds can make the skin less hospitable to lice or mange mites when consumed).

Pigs: Pigs, being omnivores, will root up burdock and eat the roots. In a way, they self-harvest a nutritious tuber. Small-scale farmers have observed pigs eating burdock roots with relish when they encounter them. Those roots provide fiber and prebiotics, perhaps supporting healthier digestion in the pig. Some farmers intentionally toss burdock roots (leftover from weeding) to their pigs as a natural deworming aid – the idea being that burdock’s bitterness and cleansing action might help expel internal parasites or at least improve gut health. This is anecdotal, but aligns with herbs like burdock often being part of traditional deworming blends for livestock.

Preparations and Methods:

For feeding: The easiest way to give burdock to animals is dried root powder mixed into feed. For instance, a horse or cow can have 1–2 tablespoons of burdock root powder in its grain ration daily over a few weeks as a health supplement. For smaller animals (goats, sheep), a teaspoon or two is sufficient. The root can also be given as a tincture (alcohol extract) dripped into the mouth, but for large animals this is less practical except under guidance.

For topical use: A strong burdock tea or infusion of the root and/or leaves can be made (by boiling 50g of herb in a liter of water) and applied as a wash to skin conditions on animals. It’s gentle and helps with hot spots, rashes, or fungal infections. Some natural farmers combine burdock with other herbs like calendula and thyme to make a livestock wound spray.

For poultices: Fresh burdock leaves can be slightly crushed and warmed, then applied under a bandage to, say, a horse’s swollen leg joint or a cow’s infected wound. The leaf’s moisture and compounds help draw out fluids and reduce swelling (much like how plantain or comfrey are used).

In feed mixes: Burdock root is often included in herbal feed mixes with things like garlic, kelp, nettle, and flaxseed for an all-purpose health boost. In chickens, for example, finely chopped fresh burdock leaves can be mixed into scratch grains occasionally. Chickens will pick at it; it might support their immune health and act as a mild vermifuge.

Case Example (Traditional Vet Use): A 19th-century farm journal might mention using “burdock leaves boiled in lard” to make an ointment for horses’ skin eruptions or for soothing the udders of cows. And indeed, modern Amish farmers still use an ointment known as “B&W” (Burns & Wounds) that often includes burdock leaf for treating livestock wounds, showing the continuity of herbal vet practices.

Observations of Impact: Many horse owners who supplement with burdock root report improvements such as a shinier coat, less sweet itch (allergic dermatitis) and better joint flexibility. On the flip side, one must ensure animals do not choke on burs or get entangled. There have been instances of birds or small pets (like long-haired cats or dogs) getting burdock burs stuck in fur – requiring careful removal (hence one might consider burdock “pesty” to pets in that context!). However, those same burs historically were used to rid dogs of fleas: one remedy involved brushing a dog with a bunch of burdock burrs, which would snag fleas and their eggs from the fur (imagine a natural Velcro comb).

In summary, burdock as animal medicine is an extension of its human use: a gentle detoxifier, skin healer, and nutritive tonic. It’s a great example of how “weeds” can be reframed as multi-species remedies on the farm. Through prudent use, burdock can improve livestock health holistically – though farmers remain cautious of its physical nuisance (burrs) and ensure it’s given in controlled ways.

From the perspective of the animals themselves, they often self-medicate if given access: many a goat has eaten burdock when feeling unwell, and horses will seek it out if browsing hedgerows containing it. This hints that animals intuitively recognize burdock’s benefits (as part of zoopharmacognosy). Facilitating that – by drying roots for winter or allowing some burdock in pasture margins – can be part of an ethical, natural animal care regime on regenerative farms.

6. Practical Regenerative Applications (Hands-On Systems)

Burdock offers numerous practical uses for farmers, gardeners, and land stewards looking to work with nature. From on-farm fertilizers to pest control to soil improvement strategies, here’s how burdock can be harnessed in various systems:

Garden Applications

Fermented Plant Juice (FPJ) / Fermented Plant Extract (FPE) Recipes: Practical Wisdom: Burdock’s vigorous growth and nutrient-rich biomass make it an excellent candidate for making homemade liquid fertilizers. A simple FPJ recipe from Korean Natural Farming using burdock might go as follows: Collect young burdock leaves (and even tender stems) – aim for ~1 kg of plant material. Chop it finely and mix with ~0.5–1 kg of brown sugar (1:1 ratio by weight). Place in a jar loosely covered. Over about 7 days, the mixture will liquefy as osmosis draws the plant juices out and fermentation begins. The resulting dark liquid can be strained; this is the FPJ. Burdock FPJ is packed with growth hormones (gibberellins, etc.) and minerals from the plant, and farmers use it diluted (usually 1:500 to 1:1000 in water) as a foliar feed or soil drench. Benefits: This FPJ can stimulate plant growth, improve soil microbial activity, and is essentially a way to capture and redistribute the “essence” of burdock’s accumulated nutrients. Gardeners report that using an FPJ made from wild weeds like burdock and dandelion gives their veggies a noticeable boost in vigor – likely due to micronutrients and phytohormones present. Fermented Extracts: Another method is making an anaerobic plant extract (often called fermented plant juice in some contexts) by submerging burdock leaves in water (optionally with a bit of molasses) and letting it ferment for a couple of weeks. The liquid is then used as liquid fertilizer around plants. Because burdock leaves have a decent N content, this ferment can act as a mild nitrogen source and soil conditioner.