Beneath the humble pink-purple blossoms of red clover lies a story as expansive as the meadows it brightens. Once a modest European wildflower, Trifolium pratense has journeyed with farmers, healers, and pollinators across continents, fixing nitrogen in tired soils, sweetening the diets of bumblebees, and lending its gentle estrogen-like compounds to generations of women seeking balance.

Today, this “living green alchemist” is enjoying a renaissance in regenerative fields and herbal cups alike. Plant it, and it stitches degraded earth back together with deep taproots and microbial partnerships; steep it, and it delivers a mineral-rich tonic once prized as a spring cleanser and skin ally. From Vermont’s state emblem to Cherokee lung tonics, from medieval crop rotations to modern menopause studies, red clover keeps proving that a single plant can nourish land, livestock, and people in one elegant sweep.

As you read on, let this profile reveal how a seemingly ordinary legume became a bridge between ancient folklore and cutting-edge soil science, inviting us to rethink what abundance really looks like when we partner with nature’s quiet overachievers.

Overview & Botanical Profile

Plant: Trifolium pratense L. (Red Clover)

Common Names: Red clover, purple clover, meadow clover, cow grass, bee-bread clover (among English names). Known as trèfle rouge (French), Rotklee (German), trébol rojo (Spanish), etc., reflecting its global presence.

Family: Fabaceae (Pea family – the legume family).

Native Range: Old World origin – native to Europe, North Africa, and temperate Asia (from the British Isles and Mediterranean across to Mongolia and the Himalayas). It thrived in meadows and open woodlands of its native range.

Current Global Distribution: Now naturalized and cultivated worldwide in temperate regions. Brought to the Americas by European settlers in the 1500s, it is found throughout North America and other continents as a forage and cover crop. Red clover is the state flower of Vermont and was even designated a national flower of Denmark, symbolizing its cultural spread.

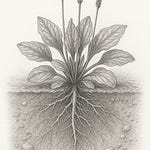

Physical Description: A short-lived perennial herb (often biennial) that grows 20–80 cm tall. Stems are erect or ascending and usually hairy. Leaves are alternate and trifoliate (three leaflets), each leaflet oval (1–3 cm long) with a distinctive pale “V” mark across the green surface. Stipules at the leaf bases are conspicuous and taper to a point. Flowers are borne in dense, rounded heads ~2–3 cm across, each head containing many tubular florets of rosy-purple color (occasionally white). The blossoms are fragrant and nectar-rich, attracting bumblebees and other long-tongued bees. Red clover develops a deep taproot (up to 1 m) in its first year, with branching lateral roots in upper soil layers. This root system helps break up soil, tolerate mild drought, and support nitrogen-fixing bacteria in root nodules. Pods are small and contain 1–2 seeds each. Overall, red clover appears as a lush, mat-forming wildflower with soft hairy leaves and vibrant pinkish-purple blooms nodding above the foliage.

1. Cultural Wisdom (Ethnobotany, Mythology, TEK)

Global Traditions:

List and compare all world regions using this plant: Red clover has been embraced in Europe, Asia, and the Americas as both a nourishing fodder and a healing herb. In its native Europe, it was one of the first plants intentionally cultivated by early farmers (Scientific Evidence: historical records) – medieval and early-modern European farmers sowed clover to reinvigorate fallow fields and feed livestock. It became a cornerstone of crop rotation (the famous “clover and turnip rotation” of 18th-century England) due to its soil-enriching abilities and abundant forage. European folk medicine also valued red clover blossoms in teas and syrups for “purifying the blood” and treating skin ailments, a practice later carried to colonial North America (Traditional Wisdom).

As red clover spread globally, other regions integrated it into their healing modalities. Russian herbalists adopted it for skin health and respiratory complaints. In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), red clover (known via later introduction) has been used as a cooling, detoxifying herb, sometimes applied for skin conditions or as part of formulas to “remove heat and toxins” (Experiential Wisdom). In India and the Middle East, where it was introduced through trade, it’s less prominent in classical texts but has entered local herbal practice in recent times for women’s health (menopausal comfort) and as a gentle expectorant. Indigenous North American peoples began using red clover after its introduction by Europeans; for instance, it was adopted by some tribes as a tonic and ingredient in healing teas (often supplementing or replacing native clovers and alfalfa-like plants in their pharmacopeia). Despite being non-native, First Nations healers recognized its virtues: the Cherokee employed red clover blossoms in teas for coughs, as a febrifuge (to reduce fever), a gynecological aid, and as a “blood medicine” to cleanse the system. The Iroquois similarly used it as a pulmonary remedy, and the Meskwaki included clover in certain healing rituals (Ethnobotanical Knowledge). On the Great Plains and in the West, where it was introduced via pasture seed, some tribes like the Cheyenne incorporated clover into their herbal repertoire for colds and sore throats (showing how quickly Traditional Ecological Knowledge can adapt to new plants). Meanwhile, in modern Western herbalism, which draws from European and Native traditions, red clover is commonly taken as a nutritive “alterative” (blood cleanser) and gentle estrogenic herb for women – demonstrating a blend of global influences.

Historical and Indigenous usage (medicine, food, ceremony): Traditional uses of red clover show remarkable overlap across cultures, emphasizing its role in both diet and medicine. As a food, young clover greens have been eaten in salads or as cooked potherbs in Europe during lean times, and red clover sprouts (analogous to alfalfa sprouts) are consumed as a vitamin-rich food in contemporary health diets (Emerging practice). More significantly, red clover was primarily utilized medicinally. In European folk medicine, red clover blossom tea or syrup was a well-known remedy for coughs, bronchitis and whooping cough, due to its expectorant and relaxant effects. Traditional herbalists also used it topically and internally for skin diseases like eczema, psoriasis, and rashes – earning its reputation as a blood purifier that “cools” and detoxifies the body. For instance, the eclectic physicians of 19th-century America included red clover in formulas for psoriasis and cancerous lesions; an extract of the flowers was applied to cancerous ulcers and growths in the folk oncology of that era (notably it became one ingredient in the infamous Hoxsey cancer remedy). Indigenous Americans post-contact found similar uses: the Southeastern Cherokee brewed red clover blossoms in tea to treat fevers, kidney inflammation (Bright’s disease), and as a general women’s medicine for menstrual and postpartum needs. The Iroquois used a decoction for whooping cough, and the Southern Ute made a sweet red clover syrup as an abortifacient and also smoked dried clover leaves for asthma relief – a fascinating cross-cultural convergence with Old World practices (smoking clover or other herbs for respiratory complaints). It’s worth noting that many Indigenous names for clover translate to “medicine for blood” or “meadow medicine,” indicating how quickly its healing potential was recognized. Ceremonially, red clover did not attain the sacred status of native plants like sage or sweetgrass, but some healers incorporated it into sweat lodge teas and purification rites given its cleansing repute (Experiential Wisdom). Overall, historical usage paints red clover as a gentle, nourishing herb used in teas, poultices, salves, and syrups to treat a wide array of conditions – from constipation to rheumatism – often in combination with other herbs. This breadth of use, in both indigenous and European contexts, highlights red clover’s role as a pan-cultural “general tonic.”

Integration into agricultural and seasonal cycles: Culturally, red clover has long been entwined with seasonal rhythms of farming communities. In Europe, it was traditionally sown in early spring (often mixed with small grains) or frost-seeded at the end of winter, making use of spring rains for germination. Farmers observed that clover fields flourish in the cool, moist seasons and could be cut for hay by early summer. By Midsummer, clover haying was a community event – cutting the fragrant, purple-flecked fields at peak bloom for winter fodder. Its inclusion in crop rotation meant that every few years a field “rested” in clover, usually following an exhausting cereal crop; this practice was integrated into the seasonal cycle of soil rejuvenation. For example, in the traditional four-course rotation, clover was planted under a cereal in spring, grew through summer after grain harvest, overwintered, and then was plowed under in the following spring – connecting multiple seasons in one integrated cycle. Many peasant farming calendars included clover sowing and plowing dates alongside religious festivals, underscoring its importance. In North America, a custom called “clovering the land” each fall or spring became part of sustainable farm management before synthetic fertilizers (Farmers’ Wisdom). Even today, regenerative farmers time red clover planting and incorporation with the seasons: sowing in spring or late summer, mowing in mid-season to encourage regrowth, and turning it under before planting heavy feeders. Seasonally, red clover’s growth pattern made it useful as a cool-season cover – greening up early in spring, maintaining cover in autumn, and surviving mild winters. Some cultures also associated clover with weather lore: for instance, a bumper clover bloom was said to portend a hot summer or indicate when to expect the first cut of hay. Integration into seasonal ceremonies was less direct, but clover fields often featured in rural life rituals (e.g. May Day garlands sometimes included wildflowers like clover). In an agricultural sense, red clover’s lifecycle taught farmers when to sow and when to reap in harmony with nature’s timing – a practice now being rekindled in permaculture and biodynamics (where planting calendars consider the best season and even moon phase for sowing legumes). The cyclical appearance of red clover – sprouting with spring thaw, blooming at the height of summer, setting seed by fall – made it a phenological indicator as well: beekeepers, for example, would note when clover started blooming to set out hives, and pastoralists would gauge pasture readiness by clover growth. Thus, red clover has been woven into the seasonal tapestry of traditional farming, symbolizing renewal in spring and abundance in summer.

Mythology & Symbolism:

Symbolic meanings, myths, sacred practices, folklore: The clover plant (including red clover) carries rich symbolism in various cultures. Perhaps most famously, the three-lobed clover leaf was imbued with sacred meaning by ancient and medieval peoples. In Greco-Roman lore, clover’s triad of leaves was linked to triple goddesses (like the Fates or the Triple Hecate). The Druids of Celtic Britain held clover (likely including the red variety) as a charm against evil: carrying a clover blossom or leaf was believed to ward off witches and ill spirits (Mythic Tradition). Early Irish Christian myth then intertwined with this pagan symbolism – St. Patrick famously used the shamrock (a clover, typically white clover) as a teaching symbol of the Holy Trinity (Father, Son, Holy Spirit), and hence clover became a sacred plant of Ireland. Red clover, with its striking pink blossoms, was sometimes called “Saint Patrick’s flower” in folk songs, and if a rare four-leaf clover was found among the patches (regardless of clover species), it was considered an extraordinary omen of good fortune. An Irish medieval rhyme encapsulates this belief: “One leaf for fame, one for wealth, one for a faithful lover, one for glorious health.” Each of the four leaves in a lucky clover was thus assigned a blessing – and finding such a clover was akin to a magical boon. Red clover’s frequent presence in hay meadows meant rural folk often encountered these “lucky clovers,” feeding a robust folklore around them. In some European folk customs, clover wreaths were made for Midsummer’s Eve and hung on barns to protect livestock from fairy mischief.

In Wiccan and contemporary pagan practice, red clover is seen as a herb of protection, love, and prosperity (Vibrational folklore). Witches and cunning folk would strew clover in the corners of the home or stable to guard against hexes. Likewise, red clover worn or carried was thought to attract a loving partner – an association with Venusian energy perhaps due to its gentle pink color and honey-sweet nectar. This gave rise to clover being included in some love sachets and potions in European folklore. Another symbolic aspect is resilience and vitality: clover’s ability to thrive in poor soil and return each spring made it a symbol of vital life-force and promise. The language of flowers in the Victorian era assigned red clover the meaning of “industry” or “be industrious,” referencing how bees industriously gather from it and how it diligently improves soil (Symbolic Insight).

There are also instances of clover appearing in myths and literature: In one tale, clovers were believed to bloom most richly where fairies danced the previous night, connecting the plant to fairy lore. Another folk belief held that carrying a red clover blossom in your pocket would ensure success at work and keep you safe on journeys. Symbolically, the color red-pink of its flower was sometimes associated with the heart, leading to an idea that red clover could bring emotional healing or courage when worn. This crosses into the realm of subtle symbolism: modern flower essence practitioners consider red clover essence helpful for maintaining calm in collective crises (preventing panic – see Bioenergetic section), so in a sense red clover symbolizes inner peace amid chaos.

In summary, through myth and lore, clover (red clover included) has come to symbolize good luck, protection, sacred trinities, and harmonious balance. From ancient triune goddesses to Christian Trinity to folk magic, the humble three-part clover leaf carries deep archetypal meaning. Red clover’s prolific blossoms, nourishing to bees and livestock, reinforce its image as a prosperity and nurturing charm – a plant that brings blessings to both land and people. Even today, a field of blooming red clover evokes feelings of hope, abundance, and natural grace, echoing the layers of mythos it has accrued over millennia.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK):

Ecological roles and stewardship practices: Within Indigenous and traditional farming communities, knowledge of red clover’s ecological role developed where the plant became available. Although Trifolium pratense is not originally a North American native, First Nations farmers and healers quickly observed its beneficial impact on the land (Experiential TEK). They noticed that where clover grew, soils were richer and plants around it grew more robustly the following season – essentially recognizing its nitrogen-fixing ability long before scientific explanation. For example, Cherokee farmers in the 19th century, integrating European-introduced crops, observed that corn planted after a clover cover yielded better (an insight aligning with ancient European practice). This became part of a stewardship practice: rotating fields into clover pasture to let the soil “rest and breathe.” Traditional ecological knowledge thus began to include “clover as healer of the Earth.” An old agrarian saying encapsulates this: “Clover and Mother Earth are sisters – one feeds the other.” By this wisdom, farmers understood that by planting clover they were feeding the soil, and in return the soil would feed the people in subsequent years (Reciprocal TEK practice).

In terms of stewardship, traditional farmers exercised practices such as saving clover seed from the healthiest patches, and inoculating the soil (even if indirectly) by moving a bit of soil from an established clover field to a new field – essentially transferring the rhizobial bacteria (folk inoculation). This mirrors modern advice to inoculate clover seed with Rhizobium bacteria. Some indigenous gardeners, after seeing clover’s effect, would call it “green manure” in their own language and make a point to lightly till it in as an offering to the earth. Traditional European smallholders had similar practices: they would plow under the clover at a certain stage (“ploughing in the red bloom”) to maximize its soil enrichment, timing this by phenology (e.g. when oak leaves reached a certain size). This demonstrates a form of TEK where timing and technique (when to cut, when to turn, how much to leave for regrowth) were refined over generations.

Ethical relationships and ceremonies: While red clover may not have a specific sacred ceremony in older indigenous culture (given its non-native status), modern herbalists and seed keepers have folded it into ethical harvesting and planting practices. Many practitioners treat red clover as a respected living being – asking permission before harvesting and offering gratitude after, consistent with indigenous harvesting ethics (Reciprocity). For instance, herbalists might leave an offering of tobacco or a silent prayer in a clover patch after gathering blossoms for medicine, acknowledging the plant’s spirit. In community gardens, some incorporate clover seeding into ceremonies of restoration – literally casting clover seeds in a ritualistic manner while voicing intentions to heal the land. This can be seen as a new TEK-informed ceremony: using clover as a symbol and agent of regeneration.

Furthermore, indigenous-led agroecology projects today often emphasize ethical relationship with all cover crops: grow them not just for utility but out of respect for how they support the whole ecosystem. In this sense, farmers speak of “letting the clover do its work” and not forcing it. For example, rather than mowing it to stubble immediately, a steward may decide to let it bloom fully so pollinators feast, even if it means slightly less biomass for soil – an ethical trade-off valuing the ecosystem. Traditional ecological principles advocate such balance. There are also accounts of elders instructing that when clover is used to heal degraded fields, one should “thank the clover and return the favor” – meaning, once the clover’s purpose is served, allow some of it to reseed or find it a new home instead of simply destroying it all. This reflects a reciprocal ethos in line with TEK: the plant helps us, we ensure its continuation.

Overall, emerging TEK around red clover emphasizes stewardship practices like crop rotation, seed saving, minimal chemical input, and mindful harvesting. By observing red clover’s interactions (with soil, insects, other plants), traditional practitioners develop guidelines – e.g. “don’t plant corn until the clover has bloomed twice” or “always leave some clover in the corners for the bees.” Such guidelines, though simple, encode ecological understanding akin to scientific knowledge: that clover needs time to fix nitrogen, that pollinators need habitat, etc. This blend of observation, ethics, and practice constitutes a living TEK for red clover, continually enriched by both indigenous wisdom and farmer experience.

Cultural Disruption & Rematriation:

Impact of colonialism or modernization: Red clover’s story is intertwined with colonial agriculture – it was deliberately carried to new continents by colonizers, aiming to impose European farming models. This had mixed impacts. On one hand, the introduction of red clover by Europeans in the Americas and elsewhere disrupted native plant communities: red clover occasionally escaped cultivation and became invasive in certain sensitive ecosystems (e.g. parts of Alaska, where it can naturalize along roadsides and compete with native flora). In these cases, colonial introduction of clover (and aggressive European grazing practices) altered successional patterns and nutrient cycles, sometimes hindering native species that were adapted to low-nutrient soils – a form of ecological disruption. For instance, botanists observed that on some disturbed prairie sites, heavy sowing of clover delayed the re-establishment of native grasses and wildflowers due to the clover’s soil nitrogen enrichment favoring other weeds. Thus, a plant introduced as an agricultural boon could become a conservation challenge, illustrating unintended consequences of colonial plant transfers.

On the other hand, the decline of traditional multi-species agriculture and the rise of industrial monocultures in the 20th century meant that red clover usage itself was disrupted. As synthetic fertilizers became widespread, many industrial farms abandoned clover rotations, causing a loss of knowledge about cover cropping. This “modernization” sidelined clover and other cover crops, contributing to soil degradation that traditional rotations with clover would have mitigated. In a cultural sense, mid-century farmers were encouraged to see clover as a “weed” in pristine monoculture lawns and grain fields – a sharp turn from earlier generations that cherished clover in pastures. Chemical weedkillers and intensive tillage regimes reduced clover prevalence on farmland for several decades, eroding the intimate farmer-clover relationship that had existed. This can be seen as a cultural disruption of agro-ecological wisdom: the quiet wisdom of nurturing soil with clover was overshadowed by the short-term convenience of chemical N (Scientific Perspective). Additionally, colonial attitudes often dismissed indigenous cover crop analogs and forbade their use, further disrupting local agro-ecosystems. For example, Native American practices of interplanting nitrogen-fixing beans or groundnuts were supplanted by European clover cropping initially, and then that too was supplanted by pure chemical approaches – a double disruption of sustainable practices.

Efforts for restoration or protection (Rematriation): In recent times, there is a concerted movement to “rematriate” the land with regenerative plants like red clover, bringing back the feminine, life-giving principles of agriculture (hence “rematriation” rather than repatriation). This involves restoring the use of cover crops and reviving traditional knowledge in farming. Across North America and Europe, organic and regenerative farmers are once again planting red clover under grain crops or in fallow fields to rebuild soil health, effectively re-learning and protecting the old wisdom. Programs by organizations like SARE (Sustainable Agriculture Research & Education) have actively promoted red clover cover cropping, funding research and farmer-led trials to refine its use. This is a form of cultural restoration – re-integrating clover into standard practice and thus preserving the agricultural heritage that values biodiversity.

In indigenous communities, rematriation also means re-introducing beneficial plants in a way that respects cultural context. While red clover isn’t a pre-colonial native, some Native-led community gardens and food sovereignty projects do incorporate red clover as a bridge plant – an introduced helper that can heal depleted reservation lands. For example, a Navajo agroecology project might sow red clover on damaged pastures to restore nitrogen and invite pollinators, framing it as an act of healing guided by indigenous principles of reciprocity (the clover is welcomed as a sister helper rather than an invasive outsider). In this nuanced way, even a colonial-introduced plant can be part of decolonizing land care, if used with intention and respect.

From a conservation perspective, efforts to protect wild clover species and meadows indirectly benefit red clover as well, since it often grows alongside other clovers. Some remnant wildflower meadows in Europe that include red clover are now conserved for their biodiversity and historical value, acknowledging the plant as part of cultural natural heritage.

“Rematriation” also extends to seed sovereignty. There is a push for farmers to save their own red clover seed or source it from local, non-corporate seed producers, preserving regionally adapted strains. Initiatives like community seed libraries often include red clover due to its importance – giving farmers and gardeners free access to grow and propagate it. By doing so, communities reduce dependence on commercial hybrids or seeds treated with fungicides, and keep alive heirloom lines (for instance, older varieties like ‘Kenland’ red clover, developed in Kentucky in the 1940s, are maintained by seed savers as they are well-suited to certain climates). This reclamation of seed stewardship is very much in line with rematriation values: returning the seeds to the hands of the people and the earth.

In summary, after a period of disruption, cultural and agricultural leaders are restoring the honorable place of red clover on the land. They do this by educating new generations about cover crop benefits, by blending scientific findings with traditional know-how, and by fostering an attitude of respect for this humble yet powerful plant. Red clover is once again being seen as an ally in healing soil and community – truly a form of wisdom coming full circle. The efforts to reintegrate red clover signify healing not just of soil fertility, but of cultural memory: they rekindle an ancient partnership between farmers and the Earth, where red clover plays a vital, living role.

2. Nutritional Profile & Health Benefits

Macronutrients (protein, fats, carbohydrates):

Red clover offers notable nutritional value, especially as a forage plant. Like many legumes, it is protein-rich: the dried herbage contains about 15–20% crude protein on average, with fresh young growth at the higher end (even up to ~22% protein under ideal conditions). This high protein content makes red clover hay and pasture an excellent source of amino acids for livestock (Scientific Evidence). In fact, red clover’s protein is somewhat less soluble in the rumen than alfalfa’s, meaning more “bypass protein” for the animal (a benefit in dairy nutrition). Carbohydrate-wise, red clover forage is composed largely of fibrous carbs (cellulose, hemicellulose) – typically around 30–35% neutral detergent fiber at bloom stage – and relatively low in simple sugars and starch (it tends to have slightly higher sugars but lower starch than alfalfa). It is very low in fat (usually <3% crude fat in dry matter). For human consumption, red clover is not a staple food, but its young sprouts and greens can be eaten: these would be low in calories and fat, and provide a small amount of plant protein and fiber. Red clover sprouts are sometimes touted as a mini-“superfood” addition to salads, offering a crunchy source of protein and micronutrients with minimal carbs (Traditional Usage). As a tea or extract, red clover contributes negligible macronutrients (being more medicinal in use).

In survival or historical contexts, dried red clover flowers and seed heads have been ground into flour to extend grain (they contain some starch and protein), and cattle fed on lush clover produce protein-rich milk – an indirect nutritional benefit to humans. Overall, the plant’s macronutrient profile is characterized by high protein and fiber, making it especially valuable in diets of herbivores. For humans, its direct macronutrient contribution is minor, but indirectly, red clover protein enters our diet via meat, milk, and eggs from animals that graze it. This exemplifies how the plant converts atmospheric nitrogen into nutritious protein, a remarkable service in the food chain (Scientific Insight).

Micronutrients (vitamins, minerals):

Red clover is rich in vitamins and minerals, both in its fresh state and dried form. The blossoms and leaves accumulate significant amounts of calcium, magnesium, potassium, and phosphorus. For instance, clover herbage contains around 1.4% calcium and 0.3% phosphorus on a dry basis – that high calcium content is one reason clover-rich pastures produce strong-boned livestock (Scientific Evidence). It also provides trace minerals such as chromium, zinc, and manganese in notable amounts. Herbal literature often highlights that red clover contains chromium, which is a somewhat unusual trace mineral in herbs, potentially beneficial for blood sugar regulation. In terms of vitamins, red clover offers vitamin C and some B vitamins (especially niacin (B3) and thiamine (B1)). Fresh clover tops have a green hue indicating beta-carotene (pro-vitamin A) content as well. Indeed, one analysis notes that red clover’s abundant nutrients include “calcium, chromium, magnesium, potassium and vitamin C, as well as vitamin A and several B vitamins”. These micronutrients contribute to its traditional reputation as a nourishing tonic.

When consumed as a tea or infusion, some of these minerals (like potassium and calcium) steep out into the water, making clover tea mildly mineral-rich (Traditional Wisdom: herbal tonics). For example, women drinking red clover infusion for health are often seeking its high calcium and magnesium to support bones and relax nerves (Experiential rationale). The presence of vitamin C and bioflavonoids in the flowers also gives antioxidant value. A scientific study even found that daily intake of red clover extract (providing isoflavones and micronutrients) improved certain markers of bone health in menopausal women, likely aided by its mineral content.

In animal nutrition, the vitamins in red clover (like vitamin E, beta-carotene) help maintain livestock fertility and meat quality, while its high mineral content (e.g. calcium) is critical for milk production. This underscores that red clover is not only a source of N and protein, but a natural multivitamin-mineral supplement for grazers (Scientific Perspective).

Overall, red clover can be seen as a nutritive herb, supplying a broad spectrum of micronutrients that support metabolic functions. Whether one drinks it as a mineral-rich tea, adds the sprouts to a salad, or feeds it to animals for superior forage, the micronutrient bounty of red clover is a key part of its health benefits mosaic.

Bioactive Compounds (phytochemicals, medicinal components):

Red clover is renowned for its phytochemical richness, particularly its isoflavones – plant compounds with estrogen-like activity. The principal isoflavones in red clover are formononetin and biochanin A, which in the body can convert to daidzein and genistein, respectively. These four compounds (biochanin A, formononetin, daidzein, genistein) are potent phytoestrogens, meaning they can weakly bind to estrogen receptors and exert estrogenic or anti-estrogenic effects depending on context. Red clover blossom extracts typically are standardized to these isoflavones for use in menopausal supplements (Scientific Evidence). In addition, red clover contains coumestans (like coumestrol) and coumarin derivatives. Though red clover itself has lower coumarin content than, say, sweet clover, it does have coumarin-like substances and cyanogenic glycosides in small amounts. One such glycoside is likely trifolin (and possibly linamarin), which can release trace amounts of HCN – not enough to be toxic in normal use, but of note in fermentation or if the plant is stressed (this is related to why fresh frost-damaged clover can occasionally cause livestock slobbering or bloat issues). Red clover also provides flavonoids (like quercetin and kaempferol), phenolic acids, and volatile oils (giving the hay its sweet fragrance). Trace salicylates (aspirin-like compounds) have been identified as well, contributing to its mild anti-inflammatory action.

A particularly interesting enzyme present in red clover leaves is polyphenol oxidase (PPO). While not a “medicinal” compound for humans per se, PPO has an important role in forage: it causes protein to complex with phenols when red clover is cut, which reduces protein breakdown (hence better bypass protein for ruminants and less nitrogen loss in silage). This enzymatic action is essentially a biochemical trait that sets red clover apart from other forages like alfalfa.

Medicinally active compounds beyond isoflavones include pectic polysaccharides (which may have immune-modulating effects), and a variety of other secondary metabolites in small quantities, such as essential oil constituents like methyl salicylate (giving a subtle sweet odor). These contribute collectively to red clover’s traditional uses – for example, the expectorant property is partly due to isoflavones and partly to soothing demulcent polysaccharides; the skin-healing property is likely due to anti-inflammatory flavonoids and the blood-cleansing concept tied to its phytoestrogens and minerals aiding detox pathways.

In summary, red clover’s most studied bioactive components are its isoflavones, which have attracted scientific and clinical interest for menopausal symptom relief and bone health. However, the plant’s action is holistic, arising from a cocktail of compounds: estrogenic isoflavones, anti-coagulant and antioxidant coumarins, anti-inflammatory flavonoids, nutrient co-factors, and so on. This phytochemical synergy underlies many of the health benefits ascribed to red clover in both traditional practice and emerging scientific research.

Medicinal Uses & Clinical Evidence:

Traditional preparations (teas, salves, tinctures): Traditional herbal medicine has utilized red clover in numerous preparations for centuries. The most common is a simple infusion (tea) of the dried blossoms. Folk healers steeped a handful of red clover tops in hot water to create a mild sweet tea used for coughs, colds, and bronchial irritation (Traditional Wisdom). This tea was often combined with a bit of honey and sipped to soothe sore throats and act as an expectorant – helping “loosen” phlegm in cases of bronchitis or whooping cough. Native American practice mirrored this: e.g. Cherokee healers gave warm clover blossom tea to children with whooping cough (a gentle antispasmodic effect). Red clover was also a classic ingredient in traditional spring tonics. In Appalachia and parts of Europe, people would drink red clover and burdock root tea in springtime to “thin the blood” and clear up skin after a stagnant winter – essentially a cleansing tonic for eczema, acne, or psoriasis. Its alterative (blood-purifying) reputation led to its inclusion in famous multi-herb formulas like Trifolium Compound (an old North American herbal syrup for skin diseases containing red clover, stillack, poke, etc.) and possibly in the original Essiac tea blend (though Essiac’s formula is debated, red clover is included in the modern commercial Flor-Essence variation).

Topically, red clover salves and washes were popular for skin maladies. Healers made a strong decoction of clover to wash sores, ulcers, burns and eczema patches, relying on its anti-inflammatory and antiseptic qualities. An ointment of red clover (flowers simmered in lard or oil) was used on psoriasis and skin cancers in the 19th century folk medicine (Scientific: it was an ingredient in the Hoxsey cancer salve). The tincture (alcohol extract) of red clover blossoms is another preparation, often combined with other herbs. Eclectic physicians prescribed red clover tincture internally for syphilis, tuberculosis, and as a mild sedative for children (for example, in measles or whooping cough to ease spasms). They documented its use as a “calmative” in irritable conditions, which aligns with modern observations of its gentle estrogenic sedation that can calm nervous excitement (Traditional/Experiential).

Less common preparations included syrups (like the Ute clover syrup for asthma and as an abortifacient) and smoking mixtures (dried red clover flowers were sometimes smoked in herbal tobacco blends for bronchial issues – likely because of their mild relaxant effects on airways). In Europe, red clover was also brewed into beer or wine in some locales – not for intoxication, but as a medicinal ale for skin health. For example, a “clover ale” might be given to someone with chronic skin eruptions.

In all these preparations, red clover was rarely used alone in traditional practice; it was typically part of a synergistic formula. But its role was often as the gentle enhancer or “blood cleanser” that improved the efficacy of the mix. The persistence of these preparations in folk medicine (some are still made by herbalists today) speaks to red clover’s valued place in traditional healing systems across cultures.

Modern herbal insights and pharmacological actions: In contemporary herbal medicine, red clover is best known and studied for its benefits in menopausal and women’s health. Modern clinical research, spurred by the discovery of high levels of isoflavones in clover, has investigated red clover extract as a natural alternative to hormone replacement therapy (HRT). The evidence is mixed but promising: Some controlled studies have found that red clover isoflavone supplements can modestly reduce hot flashes and night sweats in menopausal women. A narrative review of multiple trials concluded that red clover extract showed improvement in menopausal symptoms like hot flashes, cardiovascular markers, bone density, and even cognitive function in a significant subset of women. For example, one year-long study reported that a standardized red clover isoflavone supplement prevented bone loss in the lumbar spine by 45% compared to placebo (Scientific Evidence). Another found improvements in arterial compliance (artery flexibility) in menopausal women taking red clover, suggesting a cardiovascular benefit. However, not all studies show clear benefits – some have been inconclusive or of varying quality. The consensus in reviews (e.g. by NCCIH and Cochrane) is that red clover isoflavones may help with menopausal symptoms and markers like cholesterol, but results are inconsistent and more research is needed.

Pharmacologically, the isoflavones in red clover (biochanin A and formononetin) are selective estrogen receptor beta agonists, meaning they preferentially bind estrogen-beta receptors, which can lead to bone-protective and cardioprotective effects without strongly stimulating breast or uterine tissue. This underlies why scientists are interested in them for osteoporosis prevention and heart health in post-menopausal women. Additionally, red clover extracts have shown antioxidant activity and anti-inflammatory effects in vitro, partly due to flavonoids and phenolic acids. There are even lab studies indicating anti-cancer potential: red clover isoflavones have caused apoptosis (cell death) in certain cancer cell lines (like prostate and endometrial cancer cells) and inhibited tumor growth in test-tube models. These findings tie back intriguingly to the herb’s folk use for cancers, although clinicians caution that in a living body, the estrogenic properties could be a double-edged sword – for instance, red clover is not advised for women with estrogen-sensitive breast cancer because of theoretical risk of stimulating cancer cells. Indeed, there’s a historical note that grazing animals on certain clovers had fertility issues (the “clover disease” in sheep), underscoring that the phytoestrogens have real physiological impact.

Beyond menopause, modern herbalists use red clover for skin conditions (echoing tradition). It is a ingredient in many herbal skin formulas, often taken internally as a tea or tincture to help with eczema, psoriasis, and acne. Practitioners report seeing improvement in chronic skin complaints when red clover is used over time, likely due to its lymphatic and alterative action (Experiential Evidence). It’s also used as part of detoxification cleanses and to support the lymphatic system – helping reduce swollen glands or detox after illness. Clinically, herbalists note red clover’s mild diuretic effect (it can promote gentle urine flow), as well as a possible mild antispasmodic effect useful in kids with coughs or asthma.

Another area of interest is red clover for cardiovascular health: Some studies have noted that red clover isoflavones can raise HDL (“good”) cholesterol or improve the LDL:HDL ratio in postmenopausal women, and possibly improve blood vessel flexibility. Red clover may also exert a blood-thinning effect – it has coumarin-like compounds and aspirin-like salicylates which can mildly inhibit platelet aggregation. This could explain why folk medicine saw it as heart-friendly and why it might help reduce risk of atherosclerosis when used appropriately. However, these same properties mean caution if someone is on anticoagulant drugs (see Safety below).

In summary, modern evidence and usage validate many traditional claims about red clover: it does contain constituents that support skin health, act as expectorants, modulate hormones, and improve circulation. Its role as a gentle sedative and nutritive tonic is acknowledged – people taking red clover often report subtle improvements in well-being, skin clarity, and a “balanced” feeling. Still, scientific research hasn’t conclusively proven all uses; for instance, while some women swear by red clover tea for balancing PMS or hot flashes (Experiential Wisdom), large studies show mixed outcomes. Therefore, red clover straddles the line between traditional remedy and modern nutraceutical – widely used by herbal practitioners and increasingly studied by science, offering a beautiful example of old wisdom being explored through new lenses.

Safety & Contraindications:

Allergies: Red clover is generally very well tolerated. Allergic reactions are rare, as it is not a common allergen. That said, individuals allergic to other members of the pea family (Fabaceae) or to pollen in general should exercise caution – handling large amounts of clover (especially in bloom when pollen is present) could trigger hayfever in sensitive persons (Minor experiential reports). No significant anaphylactic reactions are documented in literature.

Drug interactions: Because of its phytoestrogenic activity, red clover supplements may interact with hormone-related medications. For example, women taking estrogen therapy or birth control pills should be aware that high-dose red clover could theoretically alter hormone levels (though typical dietary amounts are too low to have an effect). Red clover’s coumarin derivatives also imply a potential blood-thinning effect; while the plant itself is much milder than prescription anticoagulants, there is a possibility that combining red clover extracts with anticoagulant or antiplatelet drugs (like warfarin or aspirin) could increase bleeding risk (Precaution advised). Thus, many sources advise avoiding high-dose red clover if one is on blood thinners unless under medical supervision. It’s notable that spoiled (moldy) sweet clover can cause hemorrhage in cattle due to dicoumarol – red clover is far less prone to that issue, but it underscores caution with any coumarin-containing plant.

Pregnancy and lactation: Red clover supplements are not recommended during pregnancy. The NCCIH specifically warns that red clover “may be unsafe for use during pregnancy or while breastfeeding”. The concern is that its estrogen-mimicking isoflavones could potentially affect the pregnancy or fetus (for instance, there’s theoretical risk of influencing fetal hormonal development). No definitive human data proves harm, but out of an abundance of caution, pregnant women are advised to avoid concentrated red clover products. Traditionally, some midwives did use mild red clover infusion to “soften” the uterus or as part of fertility blends, but such uses are anecdotal and done with careful dosing. For breastfeeding, similar caution – phytoestrogens might reduce milk supply or pass to the infant (though again, data is scarce). Until more is known, it’s prudent to err on the side of safety and avoid red clover in these stages (Safety Consensus).

Hormone-sensitive conditions: Women (or men) with estrogen-sensitive cancers or conditions (such as breast cancer, ovarian cancer, endometriosis, uterine fibroids, etc.) should consult a healthcare provider before using red clover. Because red clover’s compounds can bind estrogen receptors, there is a theoretical risk they could stimulate estrogen-positive tumor growth. Indeed, doctors cannot advise red clover as a cancer preventive because its effects are complex – it might help prevent some cancers like prostate, but could potentially promote others. The general contraindication is: do not use red clover if you have a history of estrogen-dependent cancer (e.g. ER+ breast cancer). This is a conservative stance, as some studies show anti-cancer effects, but safety first.

Other contraindications: High doses of red clover might not be suited for children, simply due to lack of research on how phytoestrogens might affect development. However, small amounts in tea for cough (a traditional use in kids) are generally considered safe by herbalists, as they’re very mild. People with bleeding disorders or about to undergo surgery should avoid red clover supplements in the weeks prior, due to the mild blood-thinning potential (similar to avoiding high-dose garlic, ginkgo, etc. pre-surgery).

Side effects: Red clover extracts (such as those used in clinical trials for up to 2 years) have shown very good safety and tolerability. Reported side effects are usually minor: some women on high-dose isoflavone pills report headaches, rash, or nausea at rates not much different from placebo. Occasionally, mild skin rash or muscle ache can occur, but these are uncommon. Interestingly, due to hormonal effects, a few individuals might experience changes in menstrual cycle (spotting or altered timing) when taking potent red clover extracts – any such effect should be a signal to reevaluate use. In tea form, red clover is extremely gentle; one would have to drink an excessive amount to feel any adverse effect (apart from maybe slight diuresis or digestive upset if one is unaccustomed).

One area of safety unique to red clover in agricultural context: Livestock bloat and slobbers. When livestock graze very lush pure clover stands, particularly red clover, there’s a risk of frothy bloat in ruminants due to rapid fermentation of proteins. Farmers mitigate this by mixing clover with grasses and not turning hungry animals onto pure, wet clover pasture. Also, a fungus sometimes grows on red clover in humid conditions (Rhizoctonia “black patch”), producing an alkaloid called slaframine which causes excessive salivation (“slobbers”) in horses. These are animal-specific issues but worth noting for those using red clover as feed.

In summary, red clover is considered a safe herb for most people when used appropriately (Scientific and Traditional agreement). The European Medicines Agency (EMA) and other herbal safety reviews classify it as having no serious risks at common dosages. Nonetheless, its hormone-like properties warrant respect: certain populations (pregnant women, estrogen-sensitive individuals, those on blood thinners) should avoid or use only under guidance. For the general adult population, drinking red clover tea or taking a standard supplement is largely safe and “well tolerated”, offering a gentle option for health support. As always, it’s wise to consult with a knowledgeable healthcare provider about any potential interactions, and to ensure any self-directed use of red clover is done in moderation and with attention to one’s body’s responses.

3. Soil & Ecosystem Roles (Ecological, Agricultural, Regenerative)

Soil Building & Nutrient Management:

Red clover is a superstar for soil improvement, long celebrated in both traditional farming and modern regenerative agriculture for its ability to build fertility and enhance soil structure. As a legume, its most famous role is nitrogen fixation: through symbiosis with Rhizobium bacteria in its root nodules, red clover pulls inert nitrogen from the air and converts it into forms usable by plants, effectively fertilizing the soil naturally. A full-season stand of red clover can fix on the order of 70–150 pounds of nitrogen per acre (about 80 kg N/ha) in a year. Studies in the Midwest US found medium red clover grown overwinter and tilled under by late spring contributed roughly 130 lb N/acre to the subsequent corn crop. This is comparable to a moderate application of synthetic fertilizer, which is why clover was historically termed “green manure.” By planting red clover, farmers enrich the soil with a slow-release nitrogen bank. Modern trials confirm that corn or wheat following a red clover cover yields as well as those given synthetic N (often hitting the equivalent of 100–160 lb N fertilizer), while also leaving less residual nitrate to leach after harvest. This demonstrates clover’s powerful nutrient management role: providing N for crops and preventing leaching losses (Scientific Evidence).

Red clover’s impact on soil structure is also significant. Its deep taproot drives channels into the subsoil, breaking up compact layers and improving aeration and drainage. Meanwhile, its network of secondary roots in the topsoil creates a fibrous mat that holds soil particles together, increasing aggregate stability. Farmers notice that soils that have hosted clover are softer, crumbly, and rich in humus – clover’s root and shoot residues add a lot of organic matter when they decompose. A clover stand can produce 2–4 tons/acre of dry biomass; when this is returned to the earth (via grazing, mowing, or incorporation), it greatly boosts soil organic carbon. This added organic matter not only feeds soil life but also improves moisture retention and nutrient cycling. Red clover’s roots also exude substances that feed beneficial soil microbes, fostering a lively rhizosphere.

The plant is particularly noted for conditioning topsoil: its roots “permeate the topsoil” thoroughly, preventing surface crusting and creating porous channels for water infiltration. In fact, red clover is often praised as an “excellent soil conditioner”. After a season or two of clover, previously heavy or cloddy soil often becomes easier to till and more friable (Experiential evidence from farmers). Additionally, as clover roots die off (for example, when the stand winterkills or is terminated), they leave behind organic residues and microbial glues that improve soil tilth.

Composting benefits and nutrient cycling: Red clover, with its high nitrogen content and moderate carbon, is a prime “green” ingredient for compost piles. Adding clover clippings or hay to compost activates the pile, heating it up due to the readily available nitrogen fueling microbial breakdown. This results in faster decomposition of high-carbon materials (like straw or leaves) – a balanced compost. Traditional biodynamic composting sometimes specifically includes legumes like clover to ensure the compost has sufficient nitrogen for efficient nutrient cycling. The nutrients in red clover (N, P, K, and micronutrients) are returned to the soil in a stable organic form via compost, thus completing a virtuous cycle. Moreover, decomposing clover tissues contain polyphenols (thanks to that PPO enzyme) that slow the release of nitrogen just enough to prevent leaching, leading to a more steady nutrient supply (Scientific detail: red clover’s PPO-bound proteins break down more gradually in soil). Farmers often practice “clover mulching” – mowing clover and leaving the cut residue on the soil surface as mulch. This not only suppresses weeds but gradually releases nutrients in place (especially N) as the mulch decays, feeding the next crop. Red clover is also known to be a good scavenger of residual soil nutrients; its deep roots can uptake leachable nutrients (like leftover nitrate after a crop) and then hold them in its biomass, which when returned to soil, recycles those nutrients rather than letting them wash away. This nutrient scavenging and subsequent release is a key part of sustainable nutrient management in rotations.

Microbial life (fungal/bacterial relationships): Red clover’s presence in a field greatly enhances the soil microbial community. First and foremost, its relationship with Rhizobium bacteria in root nodules is a classic mutualism – the bacteria get shelter and carbon from the plant, and in return fix nitrogen for the plant. Farmers often inoculate red clover seed with Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar trifolii to ensure robust nodulation. Once established, those bacterial colonies not only feed the clover but also enrich the soil when nodules slough off or decay, contributing to the soil’s pool of beneficial microbes. Red clover roots exude various sugars, amino acids, and secondary metabolites that feed soil bacteria and fungi, often stimulating a bloom in microbial biomass around the root zone. Studies have found that soils under clover contain higher populations of nitrogen-cycling bacteria and free-living nitrogen fixers, as well as decomposers that break down organic matter faster once the clover is terminated. Clover’s high-protein residues encourage nitrogen-fixing and nitrifying bacteria to flourish during decomposition.

Fungal relationships are also improved: though some legumes are somewhat selective, red clover does form associations with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF). These symbiotic fungi colonize clover roots and extend far-reaching hyphae into soil, thereby increasing the clover’s uptake of immobile nutrients like phosphorus and zinc. In return, clover provides the fungi with carbohydrates. This association can create a rich mycorrhizal network in the soil. Interestingly, research indicates that AMF hyphae can even facilitate the movement of Rhizobium bacteria across the soil to new plant roots – effectively acting as highways for beneficial microbes. In one study with a clover relative, mycorrhizal fungi helped rhizobia colonize legume roots more effectively. It’s plausible similar cooperation occurs with red clover: Rhizophagus (an AMF) and Rhizobium working in concert to boost clover growth (Emerging Scientific Hypothesis). The presence of clover, therefore, knits together a symbiotic microbial community: bacteria in nodules, AMF on roots, and various other microbes thriving on clover’s constant supply of root exudates and decaying fine roots. Farmers often report that after a clover cover crop, their soil seems “alive” – worms, springtails, and rich fungal mycelium are evident, highlighting clover’s role in feeding the soil food web.

Mycorrhizal relationships and partnerships: As mentioned, red clover is generally a mycorrhizal plant. It enters into partnership with Glomeraceae fungi (AMF) which vastly extend the effective root system. This not only helps the clover itself (especially in low-phosphorus soils where AMF are crucial for P uptake), but also leaves behind a legacy for subsequent crops. After clover, the soil is pre-inoculated with an abundant mycorrhizal network, which can quickly hook up to the roots of the following crop (such as wheat or corn), giving that crop a head-start in nutrient access and stress resilience (Practical Observation). In fact, cover cropping with clover can prevent the drop in mycorrhizal fungi that would occur in a bare fallow. Therefore, clover serves as a bridge for mycorrhizae between cash crops, maintaining those beneficial fungi in the system year-round. Mycorrhizae also improve soil structure by binding soil particles with glomalin, further benefiting soil health.

Beyond mycorrhizae, red clover exhibits allelopathic and associative interactions with other plants and microbes. For instance, clover roots produce mild exudates that can suppress some pathogenic soil microbes or at least compete with them. Some studies suggest that certain clover cultivars exude substances that reduce nematode populations or inhibit fungal pathogens of subsequent crops (Innovative finding, though not universal). This is an area of ongoing research: whether clover can be bred or selected to be more suppressive of soil-borne diseases. Regardless, it’s clear that clover’s dense root system fosters a microbial environment that tends to outcompete many opportunistic pathogens simply by supporting a diverse beneficial community (Emerging hypothesis in soil biology).

In summary, red clover is a microbial ally in the soil: it invites nitrogen-fixing bacteria, collaborates with nutrient-ferrying fungi, and creates conditions for a thriving microscopic ecosystem, which in turn yields a healthy, fertile soil for future plants (Scientific and Practical consensus).

Biodiversity & Wildlife Support:

Supported species (insects, animals, fungi): Red clover fields are teeming with life, making them important for on-farm biodiversity. Pollinators are among the chief beneficiaries. The lush pink flower heads of red clover produce abundant nectar, especially in mornings and evenings, and are particularly favored by bumblebees (genus Bombus). Bumblebees, with their long probosces, can easily reach into the tubular florets for nectar, and in doing so they pollinate the plant. Honeybees (Apis mellifera) will also visit red clover if they are a strain with longer tongues or if the florets are short – although honeybees prefer white or crimson clover, they sometimes work red clover, especially later in the season or if other forage is scarce. In regions like New Zealand and Chile, where red clover became an economic seed crop, specific bumblebee species (e.g. Bombus ruderatus) were introduced to ensure pollination. This underscores red clover’s role in supporting these pollinator populations: clover fields provide a continuous feast of nectar and pollen for bees, butterflies, and other insects through much of the growing season (red clover can bloom from late spring into fall if mowed). Butterflies such as sulphurs (e.g. Colias species) and skippers frequent clover patches, sipping nectar. Certain butterfly larvae (caterpillars) also feed on clovers; for example, the clouded sulphur butterfly often lays eggs on clovers and alfalfa – the clover serves as a host plant for the caterpillars to eat (Wildlife interaction).

Beyond pollinators, red clover supports myriad other beneficial insects. Tiny parasitic wasps, lacewings, lady beetles, and syrphid (hoverfly) adults often visit clover flowers for nectar or pollen. Studies have found that clover ground covers in orchards and crop fields attract more beneficial insects compared to bare ground. For instance, in pecan orchards, red clover plantings significantly increased populations of predatory and parasitic insects that help control pecan pests. The clover provides them with nectar (syrphid flies and parasitic wasps need nectar as adults) and habitat (a moist, shaded understorey for ground beetles and spiders). Farmers thus use clover strips as part of integrated pest management, effectively making it a beneficial insectary.

Larger wildlife also utilize red clover. It is highly palatable to mammalian herbivores: domestic livestock (cows, sheep, goats, horses) eagerly graze it, and wild herbivores do as well. Deer and elk relish red clover if they find it in meadows or food plots, gaining nutrition from its protein. In fact, red clover is commonly included in deer food plot seed mixes to support wildlife – it provides high-protein forage that can improve deer herd health. Rabbits, groundhogs, and other small mammals also feed on clover foliage. The Alaska invasive plant profile notes that moose and mule deer graze red clover, and the leaves provide food for beavers, woodchucks, muskrats, and meadow voles. Red clover’s nutritive value thus propagates up the food chain, supporting herbivores which in turn support predators, etc.

Various bird species benefit too. Upland game birds like grouse, wild turkeys, and quail browse clover leaves and especially clover flowers. The high protein in clover is valuable for game birds; for instance, wild turkeys in spring often seek out tender clover in pastures. Additionally, seeds of red clover are eaten by some birds – the profile mentions that crows, ruffed grouse, and sharp-tailed grouse eat clover seeds. While red clover seed is small, these birds pick through fall vegetation to find the nutritious seeds. Insectivorous birds also indirectly benefit because clover-rich fields harbor plenty of insects; swallows and others will swoop low over clover fields catching the flush of bugs that rise. In U.K. meadows, researchers have observed more skylarks and other farmland birds in areas with clover, likely due to increased insect prey and some direct grazing on clover by geese or game birds.

Fungi: apart from mycorrhizal fungi, red clover can support other fungal life. Saprophytic fungi decompose the copious organic matter from clover, enriching soil fungal biomass. Some mushrooms may sporadically pop up in clover fields if moisture is right – though no specific edible mushroom associates strictly with clover, the general biodiversity of soil fungi is higher with continuous cover vs bare ground. Conversely, a few pathogenic fungi use clover (e.g. clover rot, Sclerotinia trifoliorum, can affect clover stands in damp weather). But from an ecosystem view, clover contributes to a diverse soil biota including fungi that play roles in decomposition and nutrient cycling.

Overall, a field of red clover is a mini-ecosystem hotspot, buzzing and rustling with life: bees humming from flower to flower, butterflies dancing above, grasshoppers and crickets sheltering below, spiders weaving webs among stems, birds foraging at dawn, and rabbits nibbling at dusk. It significantly increases on-farm biodiversity compared to a bare or monocropped field, acting as a keystone of sorts in human-managed landscapes by providing food and habitat for a variety of species (Holistic perspective).

Role as keystone or indicator species: While red clover may not be a “keystone” species in wild undisturbed ecosystems (since it’s often human-sown), in the context of agricultural ecosystems it can play a quasi-keystone role by disproportionately boosting system health. It supports pollinators which are keystone to many plant reproduction processes, and it supports soil health which is foundational to the agro-ecosystem. One could say that on a diversified farm, red clover is a keystone companion plant – remove it, and you lose fertility, pollinators, and fodder; include it, and multiple parts of the system flourish.

As an indicator species, red clover presence can tell us about soil conditions. It tends to thrive in neutral, well-drained fertile soils. If red clover volunteers or persists vigorously, it often indicates that the soil pH is in a friendly range (around 6.0–7.5) and that the soil has decent fertility or at least isn’t severely deficient in key nutrients. In contrast, if clover struggles or disappears from a pasture, it might indicate soil issues: e.g., pH has gotten too acidic, or soil is waterlogged (red clover is less flood-tolerant than white clover), or perhaps the soil is very low in available phosphorus (clover needs P for N-fixation). In lawns, the presence of lots of clover is often an indicator of low soil nitrogen – because clover can make its own N, it outcompetes grass when nitrogen is scarce (so a clover-rich lawn often means the grass was unfertilized and N-starved, allowing clover to dominate). Ironically, that indicator is self-correcting as the clover will add N over time. Some farmers use clover as an indicator of when to lime: clover disappearing from mixed pasture can signal that acidity is creeping up and lime might be needed to keep legumes happy. Also, because clover thrives where corn grows well, seeing wild red clover in an area might indicate it’s suitable for grain cultivation historically.

In a biodiversity context, red clover presence might indicate an early successional stage or a disturbed habitat that is recovering – since clover often colonizes or is seeded on disturbed ground. It’s part of the “healing” plant guild for disturbed soils (similar to how fireweed or lupines indicate regrowth after a disturbance, clover indicates active healing of soil through nitrogen and cover). In grassland improvement projects, a healthy population of red clover is an indicator of sustainable grazing management, as it suggests the pasture hasn’t been over-acidified by heavy fertilizer use and still supports legumes.

So, while not a classical keystone species in a wild ecosystem, in the context of regenerative agriculture red clover is keystone-like, sustaining numerous species and functions. And as an indicator, it’s a living gauge of soil health – robust clover means robust soil life.

Succession & Ecosystem Stabilization:

Role in ecological succession: Red clover often acts as a pioneer or early-successional species on cultivated or disturbed land – albeit usually one introduced by humans. When a field is cleared or a forest cut, and the soil lays bare, seeding red clover can jump-start succession by quickly covering the ground and improving soil conditions for whatever comes next. In natural succession absent human seeding, red clover (if present nearby) might colonize open disturbed ground like roadsides, construction sites, or landslides, given its hardy seeds and ability to grow in full sun. It’s not as aggressive a pioneer as some weeds, because its seeds don’t travel far (they tend to be heavy and not wind-dispersed), but clover can fill in patches near where it’s been historically grown.

In the planned successions of crop rotations, red clover is intentionally inserted as an intermediate successional phase – for example, after an exhausting row crop, clover is planted to restore fertility (a mid-succession restorative), and then the land moves to the next crop. In old-field succession scenarios, if a pasture with clover is abandoned, clover often remains dominant for a few years, then yields to taller perennial grasses and eventually to shrubs as natural succession proceeds. During its dominance, clover significantly alters the successional trajectory by enriching soil nitrogen. This can accelerate succession in some cases (allowing nitrophilous grasses and fast-growing weeds to invade quickly). It might also delay the establishment of natives adapted to low N (as noted in some ecological studies: exotic clovers can slow native prairie restoration by boosting soil N and favoring other invasives). Thus, clover in succession can be a double-edged sword: it stabilizes and prepares soil but also changes competitive dynamics.

One positive successional role is post-disturbance stabilization: red clover is frequently used in mixtures for erosion control and land reclamation. After wildfires or mining, agencies sometimes seed red clover (among other species) to quickly vegetate the soil, thereby preventing erosion and creating a hospitable soil environment for later successional species. Its quick growth and dense cover hold soil in place, while its roots and litter improve soil moisture and nutrient status, making it easier for perennial grasses, trees, or whatever the ultimate succession is, to get established. For example, on steep slopes or ski tracks, red clover has been planted to stabilize soil and add nitrogen, making the slope ready for a later seeding of native grasses and forbs once the immediate erosion risk is handled. In such cases, red clover is a facilitator in succession.

Impact on water cycles and erosion: Red clover is highly effective at reducing soil erosion and mediating water cycles on agricultural land. Its thick ground cover shields the soil from raindrop impact, greatly cutting down splash erosion. Its roots bind the soil, preventing runoff from carrying topsoil away. A well-established clover cover can virtually eliminate surface erosion on gentle to moderate slopes, even during heavy rains, by acting as a living carpet. Instead of muddy runoff, water percolates more into the ground under clover. Clover’s taproots also help break up hardpan, allowing rainwater to infiltrate deeper rather than pooling or running off. All this improves water infiltration and reduces both flooding and drought stress: fields with clover absorb water like a sponge when it rains (recharging groundwater and soil moisture), then slowly release moisture to deeper layers, and during dry periods the remaining organic matter and root channels help soil retain moisture for other plants.

However, one must note water use: clover itself uses water, so in extremely dry environments a thick clover cover could compete with main crops for moisture. Generally in temperate climates, the trade-off is beneficial – improved infiltration outweighs clover’s water usage by reducing evaporative losses and by enhancing soil structure for later water holding.

By preventing erosion, red clover preserves the topsoil and thus protects water quality downstream (less sediment and nutrient runoff into rivers). The impact on water cycles is thus: more water goes into the ground (replenishing aquifers), less goes as muddy runoff; more steady baseflow in streams thanks to groundwater recharge, less flashy flooding; and likely improved soil moisture for subsequent crops because the soil structure is improved.

Clover’s presence can also influence micro-climate of the soil: its cover reduces soil surface temperature and evaporation. A clover-covered soil will be cooler and moister on a summer day than bare soil, which helps maintain soil microbial activity and prevent crust formation, again aiding infiltration the next rain.

Additionally, perennial clover cover (even if just for 1-2 years) can help restore a more natural water cycle on a farm field – acting similar to a meadow in capturing rain and releasing it slowly. The deep roots also physically draw up water from deeper layers and bring some to the surface via hydraulic lift, potentially benefiting shallow-rooted companion plants at night (a subtle effect observed in some deep-rooted legumes).

In summary, red clover contributes to ecosystem stabilization by anchoring soil and regulating water flow. It serves as a resilient green “bandage” on disturbed soils, promoting a smoother transition to a stable plant community and preventing the kind of soil degradation that can permanently derail succession. It’s the plant equivalent of an eco-engineer in early succession, setting the stage for those that follow by building soil and moderating water extremes.

Companion Planting & Pest Management:

Companion benefits and polyculture roles: Red clover is a team player in the plant world – it often shows synergy when grown alongside or in rotation with other crops. As a companion plant, its most obvious benefit is supplying nitrogen to neighboring plants. In vegetable gardens, some growers sow red clover in between widely spaced rows (e.g. between sweet corn or brassica rows). The clover fixes nitrogen and can share some via root exudates or by decomposition of clippings, thereby fertilizing the neighbors naturally. For instance, red clover interplanted with sweet corn has been trialed; while living, the clover suppressed some weeds and after being mowed mid-season, it released nitrogen that boosted the corn’s yield (practical polyculture example). Another common practice is under-sowing clover with grains: farmers sow red clover beneath a cereal crop like oats, wheat, or barley (either at the same time or shortly after grain establishment). The clover grows slowly in the shade of the grain, not significantly competing, and after the grain harvest, the clover takes off and covers the ground. This yields a double benefit: a harvest of grain and then a ready cover crop to protect and enrich the soil. Studies in the Upper Midwest found that companion-seeded red clover with oats provided nearly double the fertilizer replacement value compared to clover seeded after oats (sequentially) – meaning simultaneous planting was more efficient and profitable. The clover/oats or clover/wheat partnership is a classic polyculture that remains “profitable and traditional”, as SARE noted, because it maximizes land use and improves soil for the next crop.

In perennial polycultures, red clover often features in orchard and vineyard guilds (see next sections for more detail). Its role is to act as a living mulch – covering soil to conserve moisture and suppress weeds, while adding fertility for the fruit trees or vines. Clover under vines, for example, can moderate vine vigor in fertile soils (by competing a bit and by taking up excess N) but in low-vigor sites it can add needed N when mowed and decomposed, a nuanced benefit for viticulture. In pastures, red clover is almost always grown mixed with grasses like timothy or orchardgrass; this mixed sward is far superior to a single-species stand. The grass provides structure and continuous ground cover (including during clover’s winter dormancy), while clover provides N to feed the grass and improve its protein content. Animals grazing the mixed pasture gain a balanced diet, and the risk of bloat is reduced compared to pure clover. This symbiosis between clover and grass is a cornerstone of sustainable livestock systems. Each species helps the other: the grass roots can host rhizobia in off-years and benefit from clover’s N, and clover can climb or lean on grass for support and perhaps benefit from grass pumping up K from deep soil.

Another companion benefit is weed suppression. Red clover grows densely enough to smother many weed seedlings once it’s established. In a vegetable garden, a living mulch of clover can drastically reduce weed pressure around taller crops. For example, researchers have used red clover as a living mulch in broccoli and reported fewer weeds and sometimes pest reduction. The key is managing clover height (mowing if needed) so it doesn’t overtop the crops. Additionally, red clover’s shade and soil coverage can delay the germination of certain weed seeds, essentially acting as a natural herbicide through competition and lack of light. Some allelopathic effect might also exist: clover residues left in soil have been observed to hinder small-seeded weed germination slightly (though not as strongly as, say, rye cover crop residues).

Polyculture roles: Red clover is part of many polyculture and permaculture designs. For instance, in a permaculture guild around an apple tree, one might plant red clover near the drip line as a “nitrogen fixer” guild member, along with other companions like comfrey (for dynamic accumulation) and herbs (to attract pollinators). The clover in such a guild fixes N to feed the tree, attracts bees to pollinate the apple blossoms, and its presence indicates when soil is warm enough (clover leaf-out) to plant other tender guild members (an example of an indicator use in polyculture).

In rotational polyculture, some farmers intermix clover with vegetable rotations: e.g. planting strips of clover between strips of cash crops, then alternating them year by year (a strip cropping system). This way, beneficial insects and N flow from the clover strips to crop strips, and erosion is prevented across the whole field. Red clover’s adaptability to partial shade also makes it suitable to sow under tall crops or along orchard alleys even while the main crop grows – a practice known as relay cropping.

Overall, red clover has a well-deserved reputation as the “friend of the farmer” and friend of other plants: it companions well with cereals, grasses, orchards, and many garden crops. Its benefits in polycultures include improved yield and quality of neighbors (through fertility), better ground coverage (through living mulch action), and enhanced system resilience (through pest control and weed suppression).

Natural pest and disease deterrent uses: Red clover’s contributions to pest management are often indirect but significant. By fostering a habitat for beneficial insects (as discussed, many predators and parasitoids feed on clover nectar/pollen), it bolsters natural pest control. For example, clover in an orchard can lead to more lacewings which prey on aphids in the fruit trees. In vegetable systems, clover living mulch can attract hoverflies, whose larvae devour aphids on adjacent crops (Observation in ecological pest management). Thus, one could say red clover deters pests by recruitment of their enemies (Ecological Pest Management).

In some cases, clover also acts as a trap crop. A fascinating example: research in the UK found that interplanting red clover with winter wheat significantly reduced damage from the gray field slug, a common pest, because the slugs preferentially ate the clover and left the wheat alone. The clover basically lured slugs away (and slugs feeding on clover could then be killed by molluscicides or predators, an integrated approach). This is an innovative use of red clover as a sacrificial crop to protect a main crop – turning a pest’s preference to the farmer’s advantage. Similarly, clover in gardens might distract leafhoppers or thrips away from nearby vegetables; it’s not a widely documented trap crop for insects in literature, but anecdotal evidence from companion planting enthusiasts suggests clover groundcovers can reduce pest pressure on plants like brassicas (possibly by making it harder for pests to find their target in a sea of clover, or by maintaining predator presence).

There is also evidence that clover cover crops can interrupt pest and disease life cycles. For instance, clover as a rotation crop helps control some soil nematodes by either producing compounds that nematodes don’t like or by simply not being a host (thus breaking the lifecycle of nematodes that plague grasses or veggies). Red clover is not known for strong allelopathic chemicals like rye, but it may have mild nematicidal effects; research in Europe has looked at clover cover for suppressing certain beet cyst nematodes, with some success in integrated approaches.